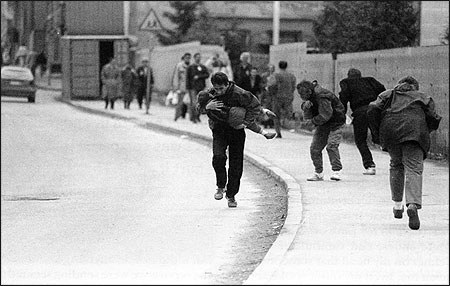

A Bosnian man cradles his child as they and others run through one of the worst spots for sniper shootings in Sarajevo. Easter Sunday, 1993. Photo by Michael Stravato/Courtesy of The Associated Press.

Courage. I think I'm the wrong person to talk about courage because I'm a coward. Being forced into action that might be described as courageous when you have no other option — that's not courage to me. What many photojournalists and reporters did is courageous. But I will give you my observation and my opinion about it anyway.

I don't think courage is a category that plays a role by itself. As far as I could see in the 15 years of working in journalism and surviving Sarajevo, journalists' courage needs a source, and so far I have recognized three such sources: insanity, lack of any clue, ideals.

Either you are completely insane to voluntarily expose yourself to snipers, mortar shells, cold, hunger and the rest of the misery I saw within the besieged city of Sarajevo for more than three years. Or you decide to ignore the danger and do your job because you have never really seen a tank before and you have no clue what it can do to you, so you are not afraid of it, which describes my case at the beginning of Bosnia's war.

I saw bombs in violent cartoons when I was little. However, Bugs Bunny would always appear alive in the next scene. I'd seen tanks before, but they did not appear that big and dangerous; they could all fit into a TV or movie screen, and they never shot at me but at someone else. So in my mind, the artillery that shot at my city in 1992 was always aiming at someone else, not at me; bad things can't happen to us, just to other people. Civilians are in general unaware of what weapons can do, unless they've dealt with them before in army training.

The shooting started in Bosnia first in cities close to the Serbian border, and although it was in our country we, in Sarajevo, still thought it was far away from us. Then it came closer and closer and artillery started pounding the Sarajevo old town. That's not where I live, so in my neighborhood we spoke about how "this is not close to us," without noticing how our safe world was shrinking.

The first idea of how close it had come was when I watched my mother preparing food at the stove next to the open balcony door while also watching nearby residential buildings being pounded by mortars. Just an average-sized park divided our neighborhood from those buildings, and when I warned her to go to the basement she replied, "This is not close to us." I realized how stupid her comment was only because a day before a neighbor had described to me what a mortar looks like, and I understood that the gunner only has to move the tube, maybe even by accident, for one or two millimeters, and his shell would land right into our kitchen. And that — was close.

Seeing people dying day by day, we — the army of the clueless — slowly realized it's wiser to stay in the basement and not to come out until it's over, which was three and a half years later. Some Sarajevans made it out and became refugees all over the world. I didn't because I could not believe this could be happening to a city in Europe at the end of the 20th century and thought it would be over in a few days.

Joining Journalists to Tell the Story

I joined the journalistic community basically because I felt I had to do something that makes sense and, I thought, after telling the outside world what is going on, something will change. With this idea in my mind, I began helping foreign reporters tell about Sarajevo's reality to the world outside. The job drew me closer and closer to danger.

When danger occurs at some spot in the city — a square is bombarded and there are dead people — for everybody else in town, this information is a signal that one has to run as far away from that spot as possible. But you, as a reporter, are the one running in the opposite direction of the crowd — toward the bad spot, to see, to hear, to capture it in the form of a photo or TV footage, in order to show and tell the world what is going on.

I was not even afraid. I sat in trenches on frontlines without really knowing what the danger from the other side looks like. I never thought about it. I had no picture of it. It was abstract. I sat there in my pink overalls, white shoes, and camouflage helmet on my head that someone had given me. Even my outfit spoke about how clueless I was.

My frequent trips to frontlines — basically outskirts of my little town — ended sometime in 1993, after I saw a tank for the first time in my life, stood next to it, and realized how small I was compared to it and how I can't hurt it at all. That's when the fear came and the courage ended. The rest of the war I tried to keep a low profile, picked up tips from experienced colleagues on how to survive and kept going the best I could. Walking down the street was almost as dangerous as sitting in a trench at the frontline, but there was no other option for me. Here was my home, my friends, my family, my life, and it was under fire, being killed every day. Pushed to the corner, having nothing to lose, you somehow are forced to do things others may call courageous, but in fact you are just trying to survive.

The Emergence of Courage

This was the difference between my foreign colleagues and me. This was not their home. They had nothing to do with my city and my world; they came here as reporters and chose to expose themselves to what I was forced to endure. They were neither insane nor clueless.

I often asked myself why are they doing this then. The answer came one night, in the middle of the war. I was ready to quit, angry about the ignorance of the world toward the suffering of my city. The idea I started with crashed. The outside world did know what was happening; we told it, but it did not do anything about it. All the reports we were sending seemed to me like screaming into deaf people's ears — they produced nothing. So there was no point for me to continue.

I was all in tears when I was explaining this to one of my colleagues, who had left the safety of his life in Paris to come here and sit with me in this stupid, pointless misery. He was listening carefully and then said after a while: "So you were up to changing the world, and it didn't work. Now you are disappointed. You think it is not worth risking your life for nothing. Your goal was set too high," he said.

He explained to me that after World War II, many Germans were asked where they were when their Jewish neighbors were taken away in the middle of the night and where they were taken and what happened to them. The most common answer was: "I didn't know." The lack of information gives them some kind of amnesty, an excuse, since it opens the door for the possibility that, would they have known, they would have done something about it. But they didn't, so they are okay.

"See, I have chosen to come here to report about what is happening in Sarajevo. To provide the information. To make sure it's on TV, it's on the radio, it's in the papers. To make sure people can't avoid the information," this colleague told me. "Not because I think it will change something right away but simply to make the information available. So one day when this is all over one way or the other, nobody can use that argument. Nobody can say: 'I did not know.'"

That night I realized how simple, realistic and noble his motive was for exposing himself voluntarily to danger. Oh, man, it was worth dying for. He will not change the world himself and might not even see a change in his lifetime. But step by step, one by one, journalists slowly widen the consciousness of humanity. It's a profession that does offer the possibility to play a small role in the overall understanding that the world is made of people who deserve our attention and action although they live on another continent. People do care about other people — they just have to know about them. Some people devote their life to being that connection between people, being that channel. This motivation makes journalists then also be courageous as a byproduct. You don't go into a war zone to report because you are a courageous person. You go because you believe in what you do so much that you get over the feeling of fear in order to achieve your goal.

The journalists who get their courage from the third source — ideals — those are the ones I envy.

Aida Cerkez-Robinson has worked for The Associated Press in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina since 1992. She started as a fixer and translator, then became a reporter, and by the end of Bosnia's war she was AP's bureau chief, a position she holds today.