Of all the papers and newsmagazines in France, one in particular should have been well prepared for the challenges of this digital era: Libération. With its witty headlines, striking photo portraits, and its passionate and often provocative coverage of arts, society, and politics, “Libé” has ridden the counterculture wave ever since it was founded by the philosopher and writer Jean-Paul Sartre 41 years ago, on the back of the 1968 student protest movement.

Part of its ability to capture the zeitgeist has been its often savvy approach to technology. Even before the Internet era, it made money with the French precursor, the Minitel, including by hawking soft porn dial-up services. Back in 1995, as Netscape was preparing to go public, the paper launched a highly successful multimedia section. Soon thereafter it built its own robust website, one of the first French newspapers to do so.

Yet today, Libé is a wreck, and its digital presence an embarrassment. Laden down by debt, it’s losing money faster than you can say “existentialism.” Its once faithful readership is giving up on it: Circulation dropped 15% last year and has since fallen below 100,000. Its website has fewer than 10,000 paid subscribers.

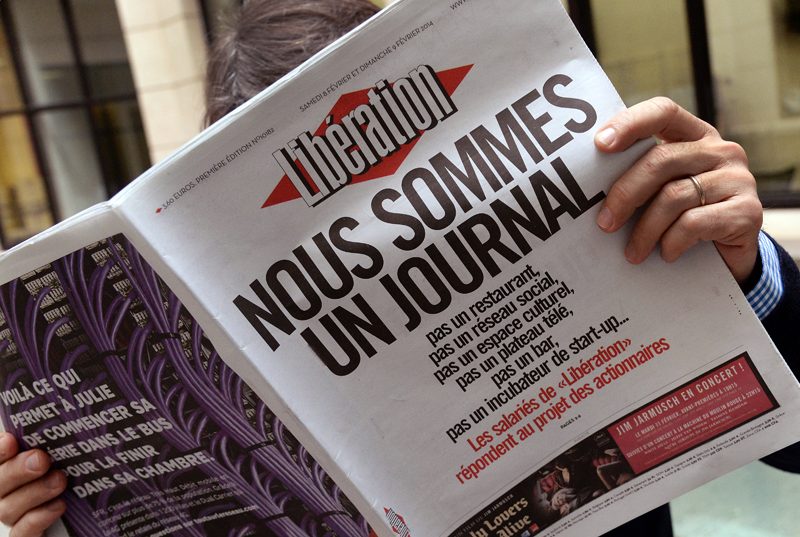

As for Libé’s 190 journalists, these days they are fighting a rearguard battle for their right to retain ink and paper. In February, after the chairman of the paper’s board, a real-estate executive, suggested exploiting the brand by creating a social network and installing a restaurant or café in Libé’s building on the edge of Paris’s trendy Marais district, the editors replied with an indignant front-page banner headline: NOUS SOMMES UN JOURNAL (“We are a newspaper”).

The message was an in-your-face slap at the board just as it was scouring for new investors, and the neo-Luddite sentiment it seemed to reflect was jarring. One longtime reader tweeted a parody version that read, “We are in the 21st Century.” It quickly went viral. Even some of those with a long attachment to the paper were taken aback. “It was a horror,” says Frédéric Filloux, who built Libé’s first website back in 1997 and now runs the Web operations of the business daily Les Echos.

In some ways, the French press is no different from its counterparts in the U.S. and around the world, as it struggles to keep up with the fast-evolving habits of its readers, the arrival of Google, the iPhone and iPad, and the decline of its advertising-based business model. Ad revenue for the French press overall has dropped by 36% since 2008, and the slide continues, according to the agency IREP; national newspaper ad sales fell 10% just last year.

But this being France, there are some Gallic twists to the tale of the press’s battle for survival. That one of the most progressive papers in terms of content has become one of the most backward in its digital strategy is an indication of the unexpected shifts and growing pressures that all are facing. Perhaps the biggest story is the increasing concentration of media power in the hands of a tiny number of wealthy business executives and financiers. That has injected some badly needed fresh capital into the press, but raises ethical dilemmas for newsrooms.

Unlike in the U.S., the level of newsroom staffing has barely changed. French journalists are protected by collective bargaining contracts that provide perks, including long vacations (12 weeks per year or more in some cases). They make it hard to shift print journalists over to write for the Web, let alone reduce the headcount. As a result, integrated newsrooms that combine digital and non-digital coverage remain the exception. “A journalist who left in 1982 and returned in 2014 would find things organized in just the same manner,” laments Nicolas Demorand, who served as Libération’s editor for three rocky years until he quit this February.

A sign of how hard it can be to change anything: Demorand at one point tried to bring forward the time of the daily editorial conference from 10 a.m. to 9.30 a.m. He had to back down in the face of fierce opposition.

There’s another French twist, too, that may help to explain some of the immobility: government subsidies. Yes, you read that correctly. The French state every year shells out about $540 million in direct funding to privately owned newspapers and magazines, and a further $1 billion or so in indirect aid, including a specially reduced sales tax for publications and income tax breaks for all 37,000 French journalists with an official press card. (That doesn’t include the $3.3 billion the government spends on public-sector broadcasting, part of which is recouped by a compulsory license fee.) The aim is to ensure a continuing pluralism of the press, and the money helps to keep afloat a number of publications that would otherwise have long since died, including the Communist party paper L'Humanité. But almost every title distributed in France gets to feed at the trough, including the international edition of The New York Times.

For all these potential brakes to change, movement is at hand. The new investors, whatever their motives, are pushing the big titles to innovate. Google, long viewed suspiciously by the French press, is helping to finance some projects through a specially created fund. And there’s no shortage of start-ups, mostly digital, some of which have broken through. The most successful is a subscription-only investigative news site called Mediapart that has made a habit of bringing down government officials—and in the process, turns a respectable profit. That its founder Edwy Plenel happens to be a former militant Trotskyist who once wrote under the name Joseph Krasny (Russian for “red”) is just one of those twists that makes France, well, France.

The publication that’s undergoing some of the biggest upheaval these days is housed in the unfashionable 13th arrondissement of Paris, in a modern building adorned with a quotation from Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” that ends with the warning, “Without the press, profound darkness.” This is the headquarters of Le Monde, France’s most famous daily, an afternoon paper founded in 1944 by Hubert Beuve-Méry.

Like Libé, Le Monde was long owned and run (poorly) by its own staff. That changed in 2010 when, after years of upheaval and financial losses, a trio of businessmen acquired it and promised to inject $150 million into its operations. They are the Lazard banker Matthieu Pigasse; Pierre Bergé, business partner of the late fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent; and Xavier Niel, a self-made billionaire who runs the nation’s fastest growing telecommunications firm. Whatever their motives—and in Paris, that’s a huge subject of dinner-table gossip—the trio’s arrival has galvanized significant change. After a series of deals, including an agreement with Arianna Huffington to launch the French edition of The Huffington Post, and the acquisition in March this year of the largest national newsweekly Nouvel Observateur, Le Monde is fast emerging as the anchor of a new heavyweight press conglomerate.

Louis Dreyfus’s office reeks of coffee and tobacco. His very job is part of the mini-revolution ushered in by the new owners. Dreyfus is Le Monde’s publisher, in charge of the business side but not running the newsroom. That’s standard practice in the U.S., but it’s a novelty for Le Monde, where the editor in chief also used to oversee the business.

Dreyfus is comfortable in the role. He started his career at Hachette in New York, where among other ventures he played a role in launching the magazine George. What’s important at Le Monde today, he says, is that there is now a real management in place, and real shareholders willing to invest in innovation. Unlike in the past, the starting point is that “we consider we cannot develop the company if there’s not the idea that it needs to be profitable.” Revolution, indeed.

He’s trimming costs where he can, which is to say, gingerly, at the same time as overseeing the group’s expansion. Unprofitable subscriptions have been axed, and some of the costly in-house printing operations have been outsourced. One of the acquisitions was a 34% stake in Le Monde’s own website, which it had sold off in harder times to a rival French group, making its journalists even more reluctant to write Web stories. The Huffington Post, which could have been a potential rival, is already in the black after two years.

So far, so good. But why would Le Monde want a troubled weekly magazine like the Nouvel Observateur? Dreyfus’s answer: because it was cheap, $5.5 million for a two-thirds stake in a publication with 500,000 subscribers. As part of the deal, the longtime previous owner, an industrialist named Claude Perdriel who made his fortune manufacturing toilets and other plumbing equipment, funded staff buyouts.

In the self-governing tradition of Le Monde, the new ownership structure was put to a vote by the journalists and approved by more than 90%, which gives Dreyfus some legitimacy. Still that doesn’t mean things are calm in the newsroom. Anxiety over staffing levels and roles is running high, both at Le Monde and especially at Nouvel Observateur. When the new owners arrived at Le Monde, 40 journalists made use of a clause in their contracts that allowed them to take a generous buyout. Dreyfus hired 40 others to replace them, in the hope of calming the concerns about the commitment to quality content, but tensions haven’t been defused.

Newsroom management is in disarray. Natalie Nougayrède, a longtime Moscow correspondent who had been editor for just over a year, stepped down in May after a revolt and the mass resignation of several of her deputies. She complained that “direct and personal attacks against my leadership” were preventing her from making the changes she thought necessary, mainly getting the paper and the website to work together more effectively. An interim editor has been appointed but the search continues for a more permanent replacement. (Dreyfus won’t discuss the matter, and Nougayrède didn’t respond to attempts to contact her.)

Five floors below Dreyfus’s office is where Corinne Mrejen sits, puffing at an electronic cigarette. She runs the 140-person combined ad sales division and is eager to make the pitch about how the new group and its range of publications now reaches a critical mass of decision makers, including 60% of French managers. Yes, of course, she studied the leaked New York Times report on its digital future and sees some obvious similarities. Mobile ads have been growing fast, but still only account for about 20% of digital ads, which themselves only constitute 25% of total revenue. Video is attractive to advertisers. So are conferences.

But neither Dreyfus nor Mrejen is under any illusions about the tough times ahead. 2014 is going to be “sportif,” Dreyfus says, a word that means “athletic” but which, under the circumstances, conjures up images of a giant obstacle course. “Le Monde is one of the most difficult companies to manage in France,” concurs Luciano Bosio, who retired recently as head of ad sales and research director at crosstown rival Le Figaro. Serge Dassault, son of the legendary aircraft pioneer Marcel Dassault and main shareholder of France’s biggest private aerospace and defense concern bought Socpresse, which owns Le Figaro, in 2004 for about $1 billion. Today, he could only dream of that sort of valuation.

He, too, has been investing, but largely to build a galaxy of commercial sites around Figaro’s own news site. They include a job search site, a ticket-sales site, and an online weather channel. Dassault’s team has also been less hesitant than their counterparts at Le Monde and other publications about wielding the axe: 120 journalists left the paper in two rounds of staff reductions in 2009-2011.

One of the defining characteristics of the French press is that it doesn’t have a clear separation between news and opinion and can often be partisan. Covering corporate news has become especially tricky now that the heads of two telephone operating companies own two of the national dailies, an arms manufacturer owns a third, and Bernard Arnault, the chief executive of luxury goods maker LVMH, a merger of Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy, controls Les Echos, the principal business newspaper. But in Figaro’s case, covering politics can be even more complicated. Dassault is a French senator and has been the subject of judicial inquiries about alleged vote buying from his constituency. When the allegations first surfaced last fall, they were big news everywhere—except in Figaro. On an inside page, it discreetly published a communiqué issued by Dassault’s lawyers, in lieu of its own story.

Edwy Plenel, for one, is incensed by the conflicts of interest inherent in the French press. But then that’s not entirely surprising, since outrage is Plenel’s mojo.

He has come a long way since his revolutionary youth, which he wrote about in a 2001 memoir. He made his mark as an investigative journalist at Le Monde; one of his most celebrated scoops was uncovering the role of French intelligence in the 1985 sinking in New Zealand of the Greenpeace boat Rainbow Warrior. He made the Elysée so nervous that it illegally bugged his phone during the presidency of François Mitterrand. He spent a total of 25 years at Le Monde, including a stint as editor in chief, but he left in 2005 during one of its sporadic crises, after attacks on his management style.

He launched Mediapart as a subscription site in December 2007. Three years later it was at break-even. Today, it’s racing toward 100,000 subscribers, each paying the equivalent of about $12 per month. This year he expects the site to make about $2 million net profit on just over $10 million in revenue. It has a staff of 50, 33 of whom are journalists. It now outsells Libération, which has almost six times as many staff members.

The secret: a laser focus on exclusive news, especially revelations of high-level political and financial skullduggery. Mediapart’s subscriptions soared in 2010, the year it broke the story about a convoluted political and financial scandal involving France’s richest woman, Liliane Bettencourt. They leaped again in 2013, after it revealed that the then-budget minister Jérôme Cahuzac, whose job included fighting tax evasion, himself had an undeclared Swiss bank account and had transferred funds to Singapore. After denying the allegations for months, Cahuzac eventually resigned, acknowledging that he had lied to parliament and to President François Hollande.

Pierre Haski, a former Libération journalist, recalls a conversation he had with Plenel back in 2006 about doing a site together. Haski turned down the idea, and together with four other colleagues created an advertising-funded news site called Rue89, which has been a success with readers but a financial failure. (Sold to the Nouvel Observateur in 2011, it’s now part of the Le Monde group.) “I didn’t believe in Mediapart,” Haski acknowledges, especially the risk of launching a subscription-only site that needed exclusive stories on a regular basis to draw readers. In their early years, both Rue89 and Mediapart surfed a wave of hostility to former President Nicolas Sarkozy. But after Hollande won the 2012 presidential election, Rue89’s readership sagged, while the Cahuzac affair buoyed Mediapart. What’s significant, Haski says, is that Plenel didn’t hesitate to go after the left as well as the right.

Plenel actually published a book of conversations with François Hollande back in 2006. But, he says, “when Sarkozy lost, I told the staff that we have a rendezvous with our independence.” He is a well-known figure in Paris, a frequent commentator on radio and TV, with a sharp tongue and bushy mustache. Above his desk in the airy newsroom not far from the Bastille hangs a framed poster for Mediapart. It reads: “Only our readers can buy us.”

Plenel’s style of dogged attack journalism leaves some of his peers uneasy. Is he a journalist or a prosecutor? When I asked him about his reputation for militancy, he answered with a history lesson, talking about Joseph Pulitzer and his aggressive coverage of the wealthy families in St. Louis in the late 1870s. “I’m tame by comparison,” he says.

He reserves some of his toughest criticism for rival French media. After Mediapart published the first Cahuzac stories, he says the biggest backlash came from other journalists, who, rather than trying to confirm the allegations, often questioned their accuracy. “It’s a very closed milieu,” he says of the mainstream French press. “For four months they were the ones who obstructed us.”

Mediapart isn’t about to mushroom into something much grander. Instead, Plenel’s thinking of starting new investigative sites devoted to sports and business. He’s planning to buy out a financial firm that put in seed money and wants to create a legal structure that would guarantee Mediapart’s independence.

He’s particularly scathing about the state subsidies handed out to the French press, especially now that most of the major titles are owned by wealthy businessmen. “I’m one of the rare liberals in this country,” he jokes. That didn’t stop him from mounting an effective lobbying campaign last year to have the sales tax reduced for journalism websites, to the same subsidized rate as print papers currently enjoy. But together with Haski and some other online publishers, he has pushed for greater transparency in the system of government aid, which is administered by the Ministry of Culture with the active participation of lobbies representing the different press groups. The amounts itemized for each publication were published in full for the first time this year.

Still, there continue to be surprises. Last December the government slipped an amendment into the national budget bill that cancelled $6 million in debt owed to the state by L’Humanité. Maurice Botbol, who heads the association representing online publishers, says that nobody in the press knew the government had lent the newspaper the money in the first place. Botbol also recounts how state funds supposedly earmarked for fostering newsroom innovation can end up being spent: One regional newspaper group used the money to buy mobile phones and tablets for its journalists.

By contrast, the fund that Google set up for the French press last year is trying to be more discriminate, and transparent, from the get-go. It has $80 million to spend over three years and projects need to be co-funded by the publication that proposes them. Ludovic Blecher, a former Libération journalist who administers the fund, says only 23 of 39 projects submitted the first year were approved, and he emphasizes that they went to a range of publications both large and small. Looking more broadly at the French press and the state of its innovation, Blecher says he sees some encouraging signs. But, he adds, “The press still hasn’t found the key to bring about cultural change. There’s a real problem of underinvestment and, I’m sorry to say, a strong conservatism in newsrooms.”

Even at Libération, change seems inevitable, however reluctant the staff may be to embrace it. It’s the latest publication to have found a new investor: Patrick Drahi, a Franco-Israeli telecom executive who lives in Switzerland and whose business is based in Luxembourg—in other words, just the sort of person the paper in its heyday would have mercilessly lampooned.

Drahi in April won a bidding contest to acquire SFR, France’s second-largest mobile operator, for $23 billion. During the takeover, he was viewed with suspicion in large swaths of the press, which may have made his job harder. In June, he agreed to put $25 million into Libération, becoming its largest shareholder. A chunk of that money will go to journalists invoking change-of-control clauses in their contracts to take buyouts, but some will go for a long-overdue digital makeover.

The paper has a new editor, Laurent Joffrin, who has, in fact, been editor twice before, in 1996-99 and 2006-11. (He’s also been editor of the Nouvel Observateur three times.) His reputation is that of a technophobe. It was during his last tenure at Libé that the paper missed a key opportunity to devise a digital strategy. He recently canceled his Twitter account after taking umbrage at someone he didn’t know who had dared to address him in the familiar “tu” form.

In a presentation to the newsroom in late June, Joffrin congratulated the journalists on being “a force of resistance in adversity.” But he also promised to “shift the center of gravity. It’s no longer on paper that things are happening.” To help him with the long overdue online focus, the new shareholders have brought in Johan Hufnagel, one of the founders of the French version of Slate, and a true digital maven. It’s a homecoming of sorts: Hufnagel served as deputy editor at Libé until 2006. Speaking before his appointment as Joffrin’s digital lieutenant, he complained that at Libération, “they are paper fetishists.”

It may not be too late to save an icon of the French press, but Libération has its work cut out to win back its readers and its influence. Ask Dreyfus at Le Monde about his competitors, and he doesn’t even mention Libé, where he, too, once worked. When quizzed, he dismisses the publication as “anecdotal.”

Now there’s a description Jean-Paul Sartre wouldn’t have appreciated.