The lunch for the summer interns was held at the editor’s swanky men’s club. The other interns and I had arrived ahead of the brass and I took my seat in one of the club’s private dining rooms, next to the woman who ran the intern program. Her name was Sheila Wolfe and we had barely smoothed the napkins onto our laps when a gentleman leaned in and whispered his audacious request: Would Wolfe and I please relocate from the center of the table to the far end lest club members be exposed to the sight of women as they passed our dining room.

I froze, less out of defiance than shock. I was naive, fresh off an enlightened college campus where sexism typically wielded a duller blade, not the sharp point of the hushed insult that afternoon in one of Chicago’s elite temples of business.

“We’re quite comfortable here,” said Wolfe. The man began to restate his request when Wolfe, a tiny, fierce force in the newsroom, quietly took hold of the table’s edge with both hands. “I said, we are sitting here.” She didn’t speak of it again. The masthead editors arrived, lunch was served, and the Chicago Tribune’s interns heard from the most powerful men at the paper.

Sometime later, while searching through archives, I learned Wolfe once had made news as a reporter when denied access to the main door of a men’s club where she had gone to cover a government official. She was redirected to a separate entry for women, completed her assignment, then publicly dismissed the door as the “contagious disease entrance.”

As I type these words, they seem even to me like some manufactured morality play from an American Girl storybook, not something that happened in my lifetime. I have been, with some exceptions, fortunate in my career and my bosses, most of whom have been men. The experience of such overt discrimination is, largely, not a millstone our daughters bear and both our gratitude and shame run deep for the indignities that many endured to get us to this place. Yet in recent conversations with dozens of colleagues, a disquiet emerged over the state of female leadership in journalism. I had noticed some familiar and unhealthy organizational patterns being replicated in the digital start-up world, so began talking to women leaders I knew, then calling others I had never met, to ask what they were seeing. The stories unspooled across generations and media types.

I heard from a broadcast executive who said there were greater opportunities for women at her network when she began her ascent 25 years ago, then ticked through a roster of prestigious producer posts once held by women but now exclusively male. From a young owner of a widely praised digital start-up who described the frustrations of trying to crack the venture capital fraternity. From an executive of a start-up who took the back seat to her male partner because she thought that would be more agreeable to the VCs. From an accomplished beat writer at a national publication crushed to learn of the pay disparity in her job.

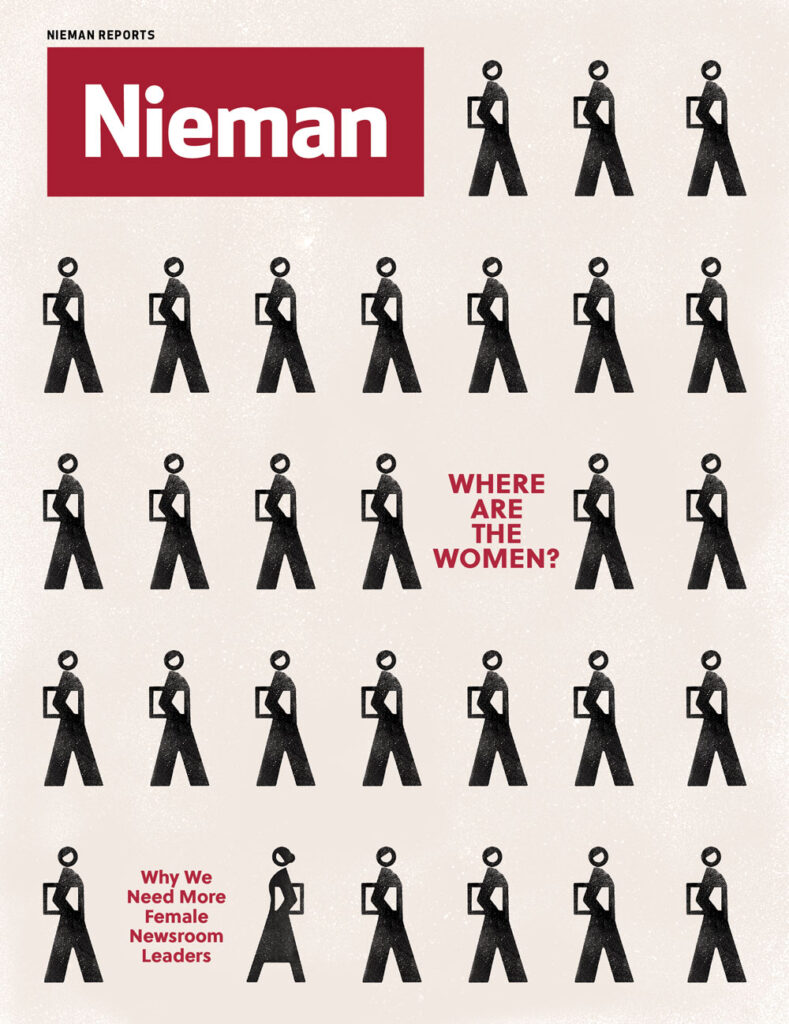

Anecdotes are, alas, merely anecdotal. And not everyone is disheartened. One colleague argues that there has been too much focus at the top of the pyramid and not enough on progress just below that and in smaller markets. But in Anna Griffin’s cover story, we find ballast to support the concerns. Women are not ascending to the top jobs in any media sector at anywhere near the rate they’re entering the journalism school pipeline. In some media quarters, their movement has been backward. Melanie Sill, who has served as editor of two newspapers and is now vice president of a public radio station, gave Griffin a bleak assessment: “We’re slipping, as an industry and maybe as a society, back to a place where women didn’t get the same opportunities and didn’t have the same influence.”

We began discussing this issue of Nieman Reports before Jill Abramson was fired as editor of The New York Times and, on the same day, Natalie Nougayrède resigned under pressure at Le Monde. Although the data were there and ripe for analysis, there is no doubt that the twin big-league departures crystalized what had been for many a lonely or latent feeling of gender regression in the news industry. No matter where people came out on the merits of the two women’s management tenures, many were especially rankled by the mostly anonymous descriptions of them as “brusque,” “pushy,” “authoritarian,” even “Putin-like.”

For a number of women managers I know—some of whom worked for men who were lionized for throwing typewriters in the newsroom—the language carried a post-traumatic wallop, with a twist. They seized upon it not merely to commiserate but to activate a long overdue conversation. One news executive wrote me: “I think this is an epic moment. Judging from the e-mail traffic I am getting, women … are filled with these stories and we at last have a platform for beginning to talk about them with younger women in a way that might actually help alter careers.” She and others are working on some strategies to do this and it is my hope that our coverage here advances that work.

I once was visited by a Japanese writer researching a book on prominent women journalists. At the end of the interview, she asked if I might recommend other women running big U.S. news organizations. “Do you,” she inquired with charming idiom, “know any other large ladies?” The phrase stuck, and for a while a group of us gathered for an occasional Large Ladies dinner.

Most of the news organizations represented at that dinner are no longer run by women. While there are many reasons for that, I wonder whether any of us foresaw the reversal or did enough, through action and example, to increase the likelihood of women successors.

I was the first woman to become editor of the Tribune. Some 20 years earlier, at a lunch for summer interns, I had watched the woman who hired me holding onto her place at the table as if our future depended on it.

I froze, less out of defiance than shock. I was naive, fresh off an enlightened college campus where sexism typically wielded a duller blade, not the sharp point of the hushed insult that afternoon in one of Chicago’s elite temples of business.

“We’re quite comfortable here,” said Wolfe. The man began to restate his request when Wolfe, a tiny, fierce force in the newsroom, quietly took hold of the table’s edge with both hands. “I said, we are sitting here.” She didn’t speak of it again. The masthead editors arrived, lunch was served, and the Chicago Tribune’s interns heard from the most powerful men at the paper.

Sometime later, while searching through archives, I learned Wolfe once had made news as a reporter when denied access to the main door of a men’s club where she had gone to cover a government official. She was redirected to a separate entry for women, completed her assignment, then publicly dismissed the door as the “contagious disease entrance.”

As I type these words, they seem even to me like some manufactured morality play from an American Girl storybook, not something that happened in my lifetime. I have been, with some exceptions, fortunate in my career and my bosses, most of whom have been men. The experience of such overt discrimination is, largely, not a millstone our daughters bear and both our gratitude and shame run deep for the indignities that many endured to get us to this place. Yet in recent conversations with dozens of colleagues, a disquiet emerged over the state of female leadership in journalism. I had noticed some familiar and unhealthy organizational patterns being replicated in the digital start-up world, so began talking to women leaders I knew, then calling others I had never met, to ask what they were seeing. The stories unspooled across generations and media types.

I heard from a broadcast executive who said there were greater opportunities for women at her network when she began her ascent 25 years ago, then ticked through a roster of prestigious producer posts once held by women but now exclusively male. From a young owner of a widely praised digital start-up who described the frustrations of trying to crack the venture capital fraternity. From an executive of a start-up who took the back seat to her male partner because she thought that would be more agreeable to the VCs. From an accomplished beat writer at a national publication crushed to learn of the pay disparity in her job.

Women are not ascending to the top jobs at the rate they’re entering the pipeline

Anecdotes are, alas, merely anecdotal. And not everyone is disheartened. One colleague argues that there has been too much focus at the top of the pyramid and not enough on progress just below that and in smaller markets. But in Anna Griffin’s cover story, we find ballast to support the concerns. Women are not ascending to the top jobs in any media sector at anywhere near the rate they’re entering the journalism school pipeline. In some media quarters, their movement has been backward. Melanie Sill, who has served as editor of two newspapers and is now vice president of a public radio station, gave Griffin a bleak assessment: “We’re slipping, as an industry and maybe as a society, back to a place where women didn’t get the same opportunities and didn’t have the same influence.”

We began discussing this issue of Nieman Reports before Jill Abramson was fired as editor of The New York Times and, on the same day, Natalie Nougayrède resigned under pressure at Le Monde. Although the data were there and ripe for analysis, there is no doubt that the twin big-league departures crystalized what had been for many a lonely or latent feeling of gender regression in the news industry. No matter where people came out on the merits of the two women’s management tenures, many were especially rankled by the mostly anonymous descriptions of them as “brusque,” “pushy,” “authoritarian,” even “Putin-like.”

For a number of women managers I know—some of whom worked for men who were lionized for throwing typewriters in the newsroom—the language carried a post-traumatic wallop, with a twist. They seized upon it not merely to commiserate but to activate a long overdue conversation. One news executive wrote me: “I think this is an epic moment. Judging from the e-mail traffic I am getting, women … are filled with these stories and we at last have a platform for beginning to talk about them with younger women in a way that might actually help alter careers.” She and others are working on some strategies to do this and it is my hope that our coverage here advances that work.

I once was visited by a Japanese writer researching a book on prominent women journalists. At the end of the interview, she asked if I might recommend other women running big U.S. news organizations. “Do you,” she inquired with charming idiom, “know any other large ladies?” The phrase stuck, and for a while a group of us gathered for an occasional Large Ladies dinner.

Most of the news organizations represented at that dinner are no longer run by women. While there are many reasons for that, I wonder whether any of us foresaw the reversal or did enough, through action and example, to increase the likelihood of women successors.

I was the first woman to become editor of the Tribune. Some 20 years earlier, at a lunch for summer interns, I had watched the woman who hired me holding onto her place at the table as if our future depended on it.