Reporters from the United States, China and Germany discuss how a story about a health issue such as avian flu can be covered competitively, with its web of connections that make it an economic, political, scientific and global news story.

Maryn McKenna, Former Senior Medical Reporter at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, now a Kaiser Media Fellow and Freelance Journalist

Stretching beyond your beat knowledge.

I spent a lot of my time over the past 10 years or so following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) around the world and, in the summer of 1997, I wrote a story about the death of a child in Hong Kong. That child turned out to be the first known case of H5N1 in a human in the world, and my story was, as far as I can tell, the first story on avian flu H5N1 that appeared in the North American media. So I've been writing about avian flu and pandemic flu for a very long time, for almost half of my too-long career as a journalist and, as a result, I've seen a lot of other journalists come in and out of the story and climb the curve that I myself climbed in learning about a very difficult topic and then realizing all the implications of that topic and frightening myself, and then learning to live with it, and making operational, as the CDC would say, that knowledge in my daily life.

Being a flu geek has taken me to places like into the flu labs of the CDC, and to the exhumation in the Arctic of the bodies of victims of 1918, and into a street in Bangkok that in English is called Chicken Alley. I stood there in 1994, watching in horror as they packed up at the end of the day and washed all the chicken droppings out of the street with a high-pressure fire hose. I covered my mouth and tried not to inhale and tried not think about what a virologist's dream that was.

Since the summer, my journey as an infectious disease and public health reporter has taken me to some interesting places, which might parallel or predict what a lot of other people are going to have to do. I've written about how businesses are strategizing pandemic flu and about what very local health departments are doing about pandemic flu. And I've written about how emergency rooms all over the United States and in North America (and likely in other countries, too) are looking at the possibility of pandemic flu as though a train is barreling down on them and they are tied to the tracks. I've written about the cultural imponderables — about the inherent resistance of people to change, not just in Asia, but in the United States, too, and how that's going to make pandemic preparations very challenging on this continent and around the globe.

I mention this because one lesson I want to send you home with is that all of us are senior journalists, and we've all been doing this for a while, whether or not we actually have beats. As we get mature in the business, we develop specialties. We're going to have to let go of that. To cover pandemic flu well we're all going to have to learn to be general assignment reporters again. I say this with some pain because I'm really proud of how good I am in my specialty.

All of us are going to have to learn new skills; we're going to have to learn about new subjects. We're going to have to do that in order to ask the right questions and especially to ask the deep questions that are going to be really important to covering the story well. If you're a health reporter, be prepared to start learning about globalization. If you're an education reporter, now would be a good time to start reaching out to law enforcement. If you already know about the business and financial world — a key part of the pandemic flu story — now would be a good time to start finding out how your local public health department works, because it's public health that's going to decide when the schools and businesses and others close their doors.

We think of the beats in newsrooms as silos. We're going to have to let go of the silos. I really believe covering pandemic flu is a web with lots of cables connected in it. If you tug on any one of them, all the others start to give.

The second lesson that I want to offer — and one I resisted for a long time — is that I really think that the pandemic story is local, local, local. The fact is, what people feel about a pandemic, whether they're willing to prepare, how well they're preparing, what we really want to tell people is what is happening in the local school district, in your neighborhood cop precinct, and in the shopping mall. That's where the real drama, the real narrative, for those of you who want to do narrative, of pandemic planning and pandemic coverage is going to be.

Here are some examples:

- Whether kids in the school lunch program are going to get fed, even though the school lunch program is a federal program, is a local story.

- Whether people will come to work if they feel ill because they live paycheck to paycheck and they can't afford to stay home is a local story. It's a story that you have to ask about locally to prove and to embody.

- Whether people will insist on going to the local hospital, even if the local health authorities have told them not to, because they have a family member who's sick and they're prepared to go through the National Guard troops at the front door of the emergency department in order to get that family member care is entirely a local story.

- If people go on with their lives as normal once the pandemic starts because they're illiterate and can't read the messages from the local public health department, or English is not their primary language and the messages haven't been translated into whatever language they use or put into their local ethnic media.

The stories on that list are situations that are going to be stories — local stories, specific and different in every area if or when a pandemic starts. But I really believe that there are stories that we can be doing now that are about preparation for a pandemic that are also very local, very specific stories, different in every place. Here's a good example. I've been talking a lot over the past year to state, and especially county and local health departments. They are deeply frustrated and scared about the national pandemic planning process. The things they say about the CDC, and about the benchmarks the CDC has set for them, and about the process by which the CDC money is getting to them, are not polite. They are not the sort of thing that most of us could put in our family newspapers, as we say. The equivalent of the last mile of the pandemic planning process in this country is just at this point not working very well. Again, something that's very local, very different in every area, something that people, even those of us who want to cover the big global and national story, we need to be paying attention to the very local, very granular details.

For a lot of science and medical people, the essential questions we ask are: "How do you know that? What's your evidence?" But I think there's another question that we have to keep in mind: "How does that work?" That's the question that will get you to the very local, very granular details of the stuff that you need to be writing about that I am now grappling with writing about. Here are s

ome examples:

- How often does the tertiary care hospital in your town get its deliveries of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies? Is it three times a day? Is it once a day? Do they have a three-day backlog? Do they have a five-day backlog? This is something I'm going to need to learn if I write about the hospital preparations.

- Have many of the changes that were supposed to beef up local and county health departments after the anthrax attacks actually happened? What really is the state of the radio communications in a particular town? What's the state of the last mile of Internet?

- If you have a Fortune 100 heavy industrial company in your municipality, where do they get their raw materials from? If there's something like Target, where are they buying? Does all of Home Depot get its fasteners from China? If they have redundancies and they've booked five fastener factories, are all of them in China? Have they thought to go to Thailand or Vietnam or somewhere else instead?

- How far away are food wholesalers that supply local grocery stores? How much of a backlog do they have? Do they go from the port with their refrigerated truck straight to a grocery store?

None of these are questions could I answer right now about the city where I now live, but I think they're questions that we all could be asking in our localities. A third lesson to guide us in this very local coverage, borrows from Peter Sandman's paradigm of hazard versus outrage. [See Sandman's comments in referred article.] Not too many people right now are convinced of the hazard. As a guide to where local pandemic stories are, look for the potentials for outrage.

Here's a very good example: After the anthrax attacks, I was embedded with a CDC anthrax investigation team in Washington. Later I started following their preparations for bioterror preparedness for other pathogens, and I sat through their smallpox vaccination planning exercises for states and localities. After the CDC trotted out its very lengthy description of exactly who was going to get smallpox vaccine, and more importantly who was not going to get smallpox vaccine (at the time the supply was very limited), a representative of the New York State Health Department stood up and said, "Everything you've said makes a lot of sense, but I have to tell you this. If you don't agree right now to vaccinate our EMS personnel, our EMS personnel will not come to work. Is that in your planning process?" And the CDC was caught absolutely flat-footed. I know of a county health department that surrounds a major state capital right now where the health department has been told that if they don't distribute respirators, which as we all know are in short supply, to the employees' families at home, then the epidemiologists and the public health nurses are not coming to work. And there's a very important hospital in New York City where the emergency department leadership has decided in advance that they are not going to use respirators there except for people who are face-to-face with known, not presumed, flu victims. And they're expecting a great deal of difficulty from the rest of their staff as a result. This is probably not the same thing that a hospital on the other side of the river has decided.

All of this is going to take time, and I have not got a solution for that. I wish I could say that getting ready to do pandemic coverage is not going to stress us more or stress our relationships with our editors more as we spend more time on this. It's something that we have to do now or we're going to be really, really sorry if the pandemic comes and we haven't.

Alan Sipress, Staff Writer, The Washington Post, formerly based in the Jakarta bureau of the Post

A Westerner in Asia: How to get beyond the obvious.

While bird flu may prove to be the most important medical and public health story of our time, it's actually much more than a medical or public health story. Medical writers need to think as broadly as possible about this story, and those who, like me, aren't medical writers, who don't have a formal background in medicine or science, the good news is there's much more to bird flu coverage.

The current episode of H5N1 began in the middle of 2003 in the poultry of Vietnam and Indonesia and later that year in Thailand. But as some reporters later revealed, those countries covered up the outbreaks for months. I started focusing on the issue in early 2004, in January, and worked on the topic probably for about two months in Thailand and Vietnam, and then put it aside and never expected to write about it again.

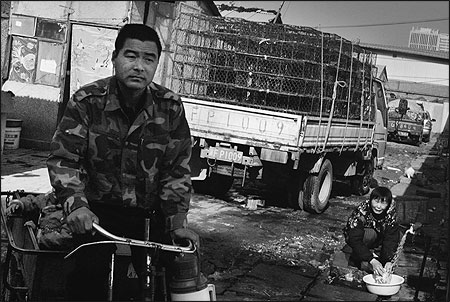

Later that year, we realized at the Post how serious of a threat bird flu was and decided to take a much deeper and broader approach to the topic. We decided to explore the economic and social changes that created conditions for pandemic and to look at the cultural and political factors that were hamstringing efforts at containing it. So, for instance, I spent a long time exploring how dramatic economic changes in East Asia, particularly agrarian changes known as the livestock revolution, had created near perfect-storm conditions for the outbreak of a pandemic, especially in the absence of the kind of biosecurity measures that American and European farms had taken a generation earlier.

For that story, I spent a couple of days in the wetlands of central Thailand profiling a chicken farmer whose life had been transformed by the livestock revolution over the last generation. He'd gone from a subsistence existence as a dirt-poor rice farmer to that of a successful businessman who could afford to buy computers and pay for college education for his kids. But even as his personal fortunes shifted dramatically, he didn't take the simple safeguards to protect his thousands of birds from infection. Instead, he packed the poultry in tightly together and lived so closely among them that the chances of the virus mutating or resorting became even greater.

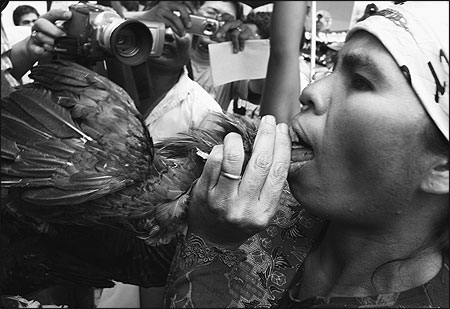

To explore the cultural dimensions of bird flu — and how long-standing traditions and lifestyles threaten to amplify the virus — I spent time with cock fighters and fighting cock breeders in Thailand and Bali, with backyard chicken farmers in Vietnam, Cambodia, central Java, with worshippers at Buddhist temples in Cambodia, who buy caged birds and then release them to win religious merit for the life to come. And for one of the last pieces from Indonesia, I spent the better part of a week in Sumatra to reconstruct the history of the famous cluster in the village of Kubu Simbelang. There were some pretty discouraging lessons about what happens when modern medicine comes up against traditional belief systems, black magic, and skepticism toward power.

To examine how the autocratic and corrupt politics of some governments in the region undercut containment efforts, I spent a fair amount of time working on accountability pieces. We wrote a piece about China's improper use of the human antiviral drug amantadine in treating livestock, which helped make this drug ineffective in treating humans infected with some strains of the virus. We wrote about Indonesia's long record of covering up and then ignoring the virus and the utter fiasco of Indonesia's effort to vaccinate poultry against the disease.

There were several virtues in taking this broader approach to the avian flu st

ory:

- It played to the advantage of being a reporter on the ground in Asia.

- The Post was able to interject new information into the international discussion about bird flu that wasn't otherwise widely available. Other reporters were much better positioned than me to cover new research or CDC findings or European Union policy debates.

- By focusing on the broader trends and the deeper dynamics, I didn't have to get caught up with trying to confirm each new case or each possible mutation in the virus that, in most cases, wouldn't have been of much interest to our generalized readership.

- We could publish what I believe were compelling and often front-page stories without having to tell our readers that a pandemic was imminent that, of course, we have no way of knowing.

Watchdog Reporting

A range of political and cultural obstacles confront reporters working this topic in Asia. Included among those are:

- Getting visas to places like Burma and Vietnam and China.

- Getting reliable information from secretive officials. In some countries, there are efforts to prevent reporters from going to sensitive areas.

- There are issues of translation. Fortunately, I spoke Bahasa Indonesia well enough that I could do some of the interviewing myself, but I was also extremely fortunate to have tremendous local journalists working with me as assistants, especially in Thailand and Indonesia.

RELATED WEB LINK

Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy

– cidrap.umn.edu/Getting around obstacles is what journalists ought to know how to do. And we use the same investigative skills that we'd use in covering local zoning boards or congressional misappropriation when we try to dig below the rhetoric of foreign governments. And, of course, we develop sources. The piece the Post published about Indonesia's long denial of its bird flu outbreak came by cultivating several Indonesian sources for more than six months, sources who ultimately went on the record with us. We also used documents, including academic studies. And I've always found the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) to be a terrific service for compiling all these in one place.

There are also documents from local governments including budgets, investigation reports, field reports, medical studies, and so forth. Part of the reason we were able to break the story about China's misuse of antiviral drugs was because of a document. We were able to get a copy of an official Chinese veterinary handbook that prescribed the use of amantadine for treating livestock that come down with bird flu. Once we had that, it wasn't so difficult to get the pharmaceutical industry officials in China to go on the record with us. We were also able to uncover malfeasance in the Indonesia poultry vaccination program by getting documents that purported in detail how much vaccine was distributed and used province by province, quarter by quarter.

Conveying the Cultural Context in Sumatra

RELATED ARTICLE

"Reporting From the Frontlines of the Flu"Here's the main difference between reporting from home and reporting from abroad: Overseas, it's even more important to keep an open mind. If you're reading about bird flu in the West, it can be too easy to fall into cultural stereotypes and to attribute the shortcomings of Asia's containment efforts to inherent cultural flaws. I'd like to take the example of the human cluster in Sumatra earlier this year. Margie Mason with the AP in Asia has been the first responder, and some of the stories she broke in Sumatra were just terrific. I had the luxury of going in a little later, then spending almost a week there trying to describe what had actually happened once the situation wasn't quite as perilous.

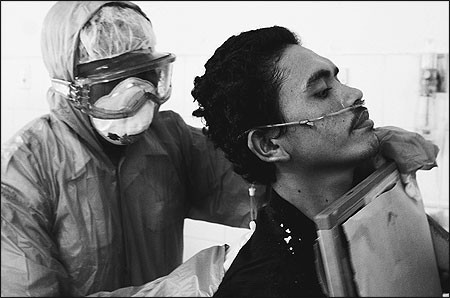

In this case, there are four siblings from a single family who fall sick with bird flu and ultimately all but one of them die. Two of the brothers who fall sick flee the hospital and literally head for the hills, refusing to accept modern medical care, including Tamiflu and other drugs. Instead, they turn to witch doctors who attempt to treat them with incense, chants and by chewing up a beetle nut-like concoction that they spit across their patient's bodies and along their extremities. Two of the most remarkable interviews I've ever had the chance to do in my life were with the witch doctors who actually carried out these procedures.

As the boys ran, they potentially spread the virus to others. No one in the family believed the illness was bird flu except one surviving brother and only at the very end of his saga. Everyone else blamed it on black magic. When the public health and veterinary officials came to the hamlet, the villagers initially chased them away, actually threatening them with violence. The villagers also refused to believe it is bird flu, and in many cases they believed it was an evil spell.

So what might we conclude about this? We think these people are so backward, illogical and crazy and they brought all these troubles on themselves. But here's how the facts looked to the family and the villagers: They'd heard that bird flu was dangerous. There was a dangerous, contagious disease. Yet all those afflicted came from a single family. And who was this family? The patriarch of this family had been the mafia godfather in that part of North Sumatra. He was widely believed to have struck a deal with the local spirit to get his power. The patriarch died a few years back and now his children and grandchildren were falling deathly ill. No one else in the highlands of Sumatra, best as we can tell, even developed a cough. Is this really a contagious disease? It looks a lot more like payback or revenge against this one family.

Moreover, the experts say that bird flu almost always comes from exposure to infected birds. But all the birds in the village and its surrounding areas seemed healthy. Samples taken by animal health officials come back negative for bird flu, so how can it be bird flu? Then look what happens to the family members who were taken to the hospital. They're admitted to the hospital, injected, given Tamiflu and, in short order, one after another, they die. Would you want to follow in their footsteps and go to the hospital, or would you want to run as fast as you could into the hills away from these strange men with masks?

I had the good fortune and the increasingly rare chance to be an American correspondent abroad. Perhaps because I lived in East Asia, it was easier to appreciate the nuances of the Asian worldviews. But there were also real advantages in being a Westerner, especially an English speaker, in covering this story.

- I had access to international experts who many local officials and academics were reluctant to contact, either for bureaucratic, linguistic or other reasons.

- In the West we're raised to be at home with resources that are available on the Internet, whether it's ProMed or academic journal Web sites, and where there are real-time reports from the AP, Reuters, Bloomberg and others. Many of even the top officials in some of these Asian countries didn't have access to or didn't access these resources.

I patrolled through all of these online sources as often as I could and then I'd go out my front door to see what was going on firsthand. I saw my job as synthesize, explore and illustrate. I wasn't going to be the first one to report on a specific outbreak in Cambodia or in downtown Bangkok, but there weren't a lot of other people who were really looking at a lot of other related issues such as:

- Larger cross-border patterns and epidemiology and the issue of genetic susceptibility to the virus, at least not a year or nine months ago.

- The recurring rivalries in country after country, between ministries of health and ministries of agriculture.

- The different ways in which poultry products are shipped and smuggled across the borders of countries in the region and beyond. Most of the experts on bird flu are affiliated with national governments and national institutions and focused on their own specific countries. Even WHO and FAO offices in various capitals understandably tended to focus on their own countries of responsibility.

Digging Where Others Can't Go

I haven't avoided public health writing altogether for the sake of writing about politics, economics and anthropology. And I might not have the specialized training of an epidemiologist, but in many ways journalists and epidemiologists share many of the same skills. What we may lack in public health training, we make up for in freedom of action. For instance, WHO investigators are often constrained by the relationships and the requirements imposed on them by host countries. We're not. So, at times, we can go to the scene, ask questions that international health investigators aren't able to, as much as they'd like to, and report findings that may be diplomatically difficult for international officials to disclose in public.

I was able to spend several days in northern Vietnam during 2004 exploring how the virus's behavior suggested it might be mutating into a more perilous form. WHO officials did not have those same opportunities to visit the field, and Vietnamese officials were cagey about reporting the information they had developed themselves. In another example, Indonesian officials long refused to admit that human-to-human transmission was taking place in their country, but I believe there's been perhaps a half-dozen clusters in Indonesia where it's likely that's taken place, if it's not absolutely proven. It puts WHO in an awkward position, because the agency doesn't want to make public comments that jeopardize its relationship with Jakarta. But we can certainly publish evidence of human transmission when we find it.

Most of what I've discussed pertains to coverage of the current prepandemic situation. If and when pandemic comes, we are not going to be spending a lot of time with cock fighters and chicken farmers. At that point, the immediate medical and public health dimensions are going to become an overriding priority. But even then, we will have to think broadly as journalists. Politics and political context will still matter and with an even greater urgency than ever before. As journalists, we should have a vital role in helping to ensure public accountability in getting the truth out and explaining why government officials and others may be hiding that truth from us.

Lu Yi, Senior Reporter and Editor, Sanlian Life Weekly, Now a Knight Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Insights from Beijing: Reporting SARS and avian flu for China's largest newsweekly.

From 2002 to 2003, we had five cover stories on SARS. From 2004 until now, we have had two cover stories on avian flu and more than 50 stories on pandemic flu and SARS. In China, there are three challenges for us in covering avian flu: Can we do it? Should we do it? How do we do it?

We have censorship in China. And it comes in three different types:

- We have "blowing in the wind" meetings when editors of magazines or newspapers attend meetings at the propaganda department twice a week. They receive a list of topics that would be better not to report. Sometimes, you can imagine, SARS and avian flu are on this list. If you want to report those topics, then you better do it this way, not your way.

- At many newspapers and magazines, there are editor meetings every week to discuss which story could be the cover story or which new story could be the special feature. After that, we have to report all those topics we discussed in this meeting to the propaganda department and, if they feel you should not be working around this story, then you just stop.

- The third type of censorship happens just before you publish your story. Although you've already finished, before you publish it you have to send the layout to the propaganda department, and the people there will check it. If they think this story is not suitable for publishing, they will just ask you to change it. Sometimes many stories tend to go nowhere.

So this is a big problem we have with such limitations; we cannot run many stories we want to run.

Because we rely on newsstand sales, our cover story is very important. If it cannot sell, it's a big problem, and people in China just don't care much about science and public health issues. So many Chinese news media, including independent magazines and newspapers, don't want to report on SARS, in part because it's highly risky; they will risk being shut down and also sales are not so good. But we are very lucky because I have a very good boss, who is open-minded and just too good to be true. The editors there have this passion for science, for public health, and they believe in enlightenment and education. So we have a big portion of science and public health reporting, with three staff science writers at our magazine, the most for a weekly magazine in China.

So how do we report these stories? First we have to bypass the censorship. If we cannot discuss a topic, can we interview this person involved in this program? We do a profile of a person, and sometimes it will pass the censorship. We also try to interview foreign scientists and foreign experts who are willing to tell true stories, rather than lie. And if I cannot run a story in China, maybe I can go abroad to run some similar stories in South Asia. I went to Thailand to write HIV stories, because although we are the first Chinese magazine that discussed the HIV epidemic in Hunan Province, after that to keep running these stories we have to go to Thailand or somewhere else.

EDITOR'S NOTE

Dr. Jiang Yanyong is the Beijing physician who in April 2003 publicized the government's coverup of the SARS epidemic in China.In 2003 we did a story on SARS, and it was a very big issue because we were the first Chinese magazine who dared to use Dr. Jiang Yanyong's picture on our cover. Before that, Time magazine had interviewed him, but no Chinese media dared to interview him or to publish anything about him and about the SARS epidemic. We have no problem connecting with him, because we have his phone number, and we know where he lives. The problem is that we cannot interview him because he lives in the military neighborhood and there are soldiers outside the neighborhood, so we have to pretend to be his family. We interviewed him in his son's home, and he told us that before he wrote letters to Western news organizations, he also wrote several letters to other Chinese media such as People's Daily and CCTV. "Nobody at these news organizations dared to do this story," he said to us, "and I just don't want to waste my time to talk with you and there's no story."

We really want to run this story, so we used some tricks to have this cover story published. At the wind-blowing meeting, we pretend we'll run another cover story and, just one day before it comes to publish, we change our cover story and publish his picture on the cover. We saw that the magazines were delivered to newsstands in Beijing; if you run bad stories about the government, sometimes they recall the copies, and we don't want that to happen. I should also say that after we published this magazine, we were punished. They sent us a new chief editor, and our original chief editor was deprived of making the final decision about the cover story and our salaries and incomes were cut about in half. That situation continued until early 2005.

With the avian flu coverage, it's different. We have two people to interview. Let's call one of them Dr. G., a virologist based in Hong Kong who was interviewed by many Western media and the Chinese newspapers and the magazines. But when I scrutinized his story, I found there are many logical gaps. I finally found another doctor, Chen Hualan, who is a tough woman, very tough. Nobody in China can interview her, because she refused to be interviewed, and she refused to talk about anything. She is the director of the National Avian Influenza Reference Laboratory in Harbin, China. She is powerful and doesn't want to be a hero. But after I read all of her articles in the medical journals, and when I'd read the other studies, I found she is the key person, and she has firsthand resources, unlike Dr. G., who just hides so much information. If I just interviewed him, I can have a good story and everybody will say, "Oh, you are brave." But the fact is, it's so biased, and so I spent a week following Dr. Hualan as she flew to Shanghai and then to Beijing, then to Harbin. Finally she would like to say something about it, and I got firsthand information. It's very important that I know these things, because people in China are terrified about avian flu. People think that if the virus is mutated, it's a bad thing. We will have a big risk. But the fact is that mutation happens all the time. We should do many more things to improve our information about this virus and not just write horrifying stories. I think it's a good story, because I also got trust from the scientists, and so we have a good story.

Image provided by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Dr. Sherif Zaki.

Harro Albrecht, Medical Writer/Reporter, Die Zeit, Germany

The Euro perspective: Once infected birds hit Germany, the story was never the same again.

In March 2005 my editor told me, "We have to get some stories about flu." I replied, with the seasonal flu stories in mind, "You know that flu is a dead story, but I can do a story about pharmaceutical companies who try to put out doomsday stories to help sell their goods." I went into reporting this story, and suddenly I found myself in a disturbing development. After three or four days I convinced myself that something different is going on here, something odd, and we have to prepare. Suddenly I found out that the German government was at work on a national pandemic emergency plan. Then I got the unique opportunity to get a firsthand copy of the national influenza pandemic plan, given to me by the director of Germany's equivalent to the CDC [Robert Koch Institut]. For 12 years I'd been in touch with him, so I knew him, and he trusted that I would cover this thoroughly.

I did cover the report thoroughly, but we ended up with a strange story. On the front page, there was this very healthy-looking woman with a scarf around her neck and a thermometer in her mouth that said, "Influenza, the Underestimated Disease." It looked like a common cold story. It was kind of strange. The headline had no word about pandemic or H5N1 or avian flu, although the whole story was about it.

But in the plan, there were no answers like how a possible vaccine would be procured or how the whole system would work. It had all kinds of advice, with a lot of use of words like "would" and "should." Even the director was not satisfied, and he was open to telling me this. And I thought, he's giving me his plan, and he is not really proud of his product. What is that?

As I noticed this, I thought that this is the first lesson for us, as reporters, for we play a very important role as facilitators between different authorities in our country. In Germany, there's a struggle between federal institutions and state institutions, and I found myself in the situations that I had to facilitate and critique one to the other as I bundled information in one place. After a while, people would be asking me, "What is this guy saying? We sit together on the commission, but we're not talking to each other." So I'd be telling them what the other person is doing. This meant I was in the middle of all kind of weird situations.

A while after the migration of birds brought avian flu to Europe in March 2005, I started to ask questions about how well the national pandemic plan was working. I asked people in all 16 federal states, went to several hospitals and talked with other officials and asked them about the plan. I asked authorities who had Tamiflu available for 30 percent of their population what they were going to do if the people from five or six other regions came knocking on their doors — coming to them from places that had Tamiflu for only five percent of its citizens. And the blunt answer was, "I think it might be good to travel during that time."

This was obviously not a real good plan. They had a nice database with all sorts of data on preparation, so I asked them to show me some data about how many rescue rovers and ventilators they had. "Do you have data about that?" And they said, "Well, no, sorry. We don't have that. If you get hold of some, let us know."

By the 14th of February, 2006, the first dozen dead swans were found at the north end of the Baltic Sea on an island in the East German part. So I went there. I had disposable boots with me to keep me from being contaminated or spreading the disease. And I found a whole bunch of people, especially people with TV teams, standing with their feet right in the feces of the dead swans. There were no tape barriers, no preparation at all, nothing. And we're moving from these dead birds to the next poultry farm. I commented in my newspaper that it was kind of crazy to be doing this. Afterwards, there were a lot of discussions.

The messages about all of this are very, very difficult, and I have to keep repeating them again and again, telling people that a seasonal flu shot is not protecting against the common cold and is not protective against the new virus that is approaching. Though we have seasonal flu vaccines, it is not that easy to produce a similar vaccine against a virus that is marching toward our area. And most important, just now the coming virus is not a threat to humans, only to birds. In case it turns into a human virus, there is a drug that might mitigate the symptoms, or might prevent death, but only if it's taken when you barely notice the symptom, which could even be a common cold. I have to repeatedly write it and write it and write it over and over, and that's what I've done.

So I explain this to readers thoroughly, make the case somehow urgent, but let them have a bit of hope by being sure they understand that the avian flu is not a deadly threat now to humans. At times, I found myself replying to questions on TV, where I was asked as an expert, and I tell people to be prepared for any crisis; "Don't think about a H5N1, but it is reasonable to prepare for anything: stockpile food, stockpile everything."

Helen Branswell, Medical Reporter, Canadian Press (CP), Canada's Domestic News Agency

How to cover an international story working the phone.

I was asked to speak because I cover the avian flu story pretty much exclusively from Toronto, which is an unusual way to do it. I'm in the print media, so I try to organize my thoughts under subheads, and the first of those is location, location and location. That's important when you're selling a house, but it doesn't have really that much to do with covering this story. There's no reason why somebody in Bangor or Chicago or anywhere can't cover this story to whatever degree they like, pretty much from wherever they are.

I wrote my first avian flu story on January 13, 2004 when the WHO was investigating 14 suspected human cases that had occurred during the last few weeks of 2003 and early into 2004; all were young children, and 12 had already died. That story said we might be seeing the early stages of a pandemic emerging. In the intervening years, I've written well over 200 stories about avian and pandemic flu and related topics. I regularly quote WHO officials from Geneva, from China, occasionally from Indonesia; I quote experts from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, universities across the United States and Canada, and into Europe. And I do it all from my desk or my phone at home. CP is a quite small agency with a very modest budget, and there are only two medical reporters. So I can't really jump on a plane at will but, for the most part, it really doesn't make much difference.

One thing, though, I need to keep in mind, and it's important for all of us in journalism to think about, is that all sources aren't created equal. In this conglomeration of different stories — all of them tied together under the subheads of avian flu and pandemic influenza — some might be of more interest to you and your readers than others. Others will be of critical interest to you and your readers. Among these various stories are:

- The vaccine story — a big, big story.

- The molecular biology story — what is it about this virus that makes it so virulent, way more virulent than any one they've seen so far? What might allow it to adapt to humans?

- A story about nonpharmaceutical interventions that we heard about things such as school closures. Would those things work?

- The story about what companies are doing and hospitals are doing to prepare for a pandemic.

- The very interesting and difficult stories about the ethical questions that a lot of people are trying to grapple with in terms of who would get vaccine first, who would get limited antivirals first. How would hospitals triage patients? What is the duty of care of health workers?

RELATED ARTICLE

"Understanding the Threat"With the ethical questions, the WHO has a big project underway on ethics. Hospitals, at least in my part of the world, are dealing with it. It's a great story. It's a difficult story, and medical people are tied up in knots about it. They don't even like to talk about it, because it's such an anathema to what they do all the time. They have to sort of try to figure out who they won't save. It's a very difficult issue. There's also the issue of modeling, which is what Marc Lipsitch does, and how much models can tell us about what might happen and how much they can't tell us about what might happen. [See Lipsitch's comments in referred article.]

Finding the Best Sources

The important thing to keep in mind is that there isn't a single flu expert out there who can effectively talk about all of these different subjects. What is fantastic is to hear a dependable source say, "This is outside of my realm of expertise." I trust them more, and I go back to them more. Anybody who wants to talk about every story regardless of what sort of subhead it comes under in flu, you really don't want to be talking to that person.

ASSEMBLING A REFERENCE BOOKSHELF ON AVIAN FLU

Creating a Bookshelf of Valuable Resources

– Maryn McKennaHow do you know how expert an expert is? There's been an explosion of experts on this issue since it hit the prime time last fall. Quite a few are selling books, and there's been an explosion in that, too. To be honest, I don't know an actual flu expert who's written a book in the past few years. None of them have had the time to do that. That doesn't mean that the people who've written these books haven't done their homework, but they have got a vested interest, and they aren't on the frontline. Add that to the mix when you're thinking about whether or not these are the right people to call.

If you're writing about the science of flu, whether it's seasonal, avian or pandemic, and you're thinking about quoting somebody who isn't a well-known, mainstream flu specialist, it's really worth doing a PubMed search on them. See what they've published on flu. Right now, a New York University medical professor who's written a book about pandemic fear is widely quoted on a variety of topics including molecular biology, with such topics as whether this virus is attaching to the right receptor binding sites, could it bind to more human sites, and what it would take to do that. Search in PubMed and the only thing that you'll find under his name is an article in Forbes — not even medical literature. So if he hasn't published anything in the medical literature on any topic at all, is he really the right person to be talking about the molecular biology of flu? Just think about that.

Who you talk to matters, both for the quality of the work that you're producing for your readers and also because the people who are taking the subject seriously read the serious work. The experts watch us; if they see us quoting people who aren't really high caliber, it's going to influence whether or not they're going to take your call.

This brings me to my next point: If you can afford it, if your bosses don't mind, or if you're freelancer and can afford it, there's no reason to stick to the continental United States. You can dial anywhere, and there are experts on this subject in

Hong Kong; Jakarta; Beijing; Atlanta and Athens, Georgia; Columbus, Ohio and Ho Chi Minh City. I call these places all the time. They're great people. There's no point in not using them. But generally I would say e-mail first. Actually, what I would say is read the study first, do your homework first. If you're going to get somebody like Dr. Nancy Cox, who is head of the Influenza Division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, on the line, you really want to know what you're talking about before you start asking her questions if you want to get her on the phone a second time.

Doing things remotely means sometimes you have to get creative. Most of the time, it doesn't matter that I'm in Toronto, but there are occasions when it really does. In May, when the Sumatra cluster was occurring, it was killing me. I was on the phone all the time, but I obviously couldn't be there. I knew that the people in the village were refusing to take Tamiflu, I knew they were afraid of it, and so I was trying to figure out a way to do that story. But I couldn't go and talk to those people about what was going on there. I couldn't get the story that others got. So I talked with a person at the University of Washington who was one of the first people that the WHO used to try to combat fears during the Ebola crises. He told me about struggling against the misperceptions that arise when white doctors come in and start pulling out bodies during an Ebola crisis. I talked to somebody at our national lab in Winnipeg who's an expert on Ebola and had recently been in Angola for the Marburg outbreak. This offered me a way to get at that story without actually having to be there and talk to survivors or people around them.

Another point I really want to make is to not forget to talk with vets. There are so many diseases that are interlinked, so vets are a huge resource on this story. Right now, H5N1 is really just a bird virus; the people who know the most about it are in veterinary medical schools, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture has some terrific experts.

People in the blogosphere have been following this story avidly for a long time. Their blogs are interesting, and sometimes they're useful and sometimes they're scary. There's a great blog called H5N1 that doesn't really offer a lot of analysis, but it's a good way to keep up on what's going on. I use that quite a bit. There's a terrific blog called Effect Measure where there's quite a bit of very useful analysis. Then there are some places that are really wildly inaccurate and full of rumors and, with the rumors, you just have to understand them and keep them in context, because some of these people see every bird that falls as H5N1 in North America and every kid that coughs has got the disease. As reporters, we need to keep an eye on blogs, but you really, really need to back-check them.

John Pope, Medical/Health Reporter, The Times-Picayune, New Orleans

Living to tell: What Hurricane Katrina can teach us about covering a pandemic.

I can relay lessons that my colleagues and I learned from covering the ghastliness of Hurricane Katrina that could stand us well in covering the next awful story that comes along. As my newspaper's local medical reporter, I was kept busy cleaning up the mess that big name correspondents left behind when they parachuted into our corner of hell, interviewed apprehensive residents, and fled after filing reports brimming with scary accounts of contagion. Some talked about the possibility of diphtheria, cholera and, so help me, malaria and yellow fever. Too many described the feted floodwater with a clichŽ I came to abhor, toxic gumbo.

Naturally, my editors came to me and said "Pope! Why don't you have this stuff?" I had a simple reason — from regular consultation with local, federal and especially state health officials, something a medical reporter must do under these circumstances, I knew these calamitous conditions didn't exist. So I was put to work doing a series of stories whose messages boiled down to two words: "Calm down."

The stories addressed such concerns as the conditions of the water and the safety of local seafood and also examined the effect of the storm on the West Nile outbreak, which was chugging along when Katrina blew through. I even found some local scientists who had evidence that let them take issue with a peer-reviewed article about the post-Katrina lead content of local soil. And in another story I was able to debunk the rumors about the mysterious respiratory condition that had come to be known as Katrina cough.

What I was doing in these stories wasn't mindless civic boosterism or a desire to put my hometown in the best possible light. No. My aim was simply to tell the truth to a couple of thousands readers who wanted to know the truth about the city they loved. And people who are reading us online at www.nola.com, where we got as many as 30 million hits a day, needed to know, because this information would be a crucial factor in helping them to decide whether to return. Besides, this was simply common sense reporting based on the evidence, or in this case, the lack thereof.

Too many journalists who had come to New Orleans, dazzled by the prospect of sensational stories amidst a ghastly background, seemed to forget the basic tenets of health care reporting, which starts with finding credible stories with good sources and good databases. Sam, the piano player, said it best in "Casablanca:" "The fundamental things apply."

Now, in our post-Katrina time, the old rules are broken. Everything in the city is broken. There's an edge to our coverage, sure. But how could there not be? But it doesn't come at the expense of fairness. The Katrina experience, especially multiple failures of government at all levels, made all of us tougher and much more skeptical about what we hear and read. And we have unavoidably become part of the story we're covering; when I encountered a storm-related situation, I often tried to wonder whether other people might be in the same predicament and, if so, whether it might be worthy of a story. It's a matter of putting ourselves in the reader's shoe.

Others have mentioned the need for positive stuff. Around the first anniversary of the storm I set out to find people who, despite the devastation, were working to make things better. And I found them — an internist who came back to New Orleans and started a clinic, which is a home for runaway teenagers and their kids, that is replacing the Charity Hospital infrastructure as a place for indigent care and a New Hampshire man who came down to St. Bernard Parish, which was blasted, and he's staying five years to build a community center and living in a tent. I hate to say the storm's good because it was horrible. But it's sort of like what Dorothy and her friends discovered about themselves in "The Wizard of Oz." They found out they could do things they didn't know they were capable of. It took this awful occurrence, but they did it. And they're going on.

In the discussion period that followed, Stephen Smith from The Boston Globe asked Helen Branswell to explore the challenges involved in keeping this story on the radar screen of editors, especially if a few seasons go by without a few huge cases to grab attention.

Branswell: I was lucky coming into it because Toronto had gone through SARS. SARS hit us, and I almost did nothing else for the rest of the year. During SARS I kept going to my editors at the beginning and kept saying, "You're not getting how big this is. You've got to get the business department writing about this because conferences are going to start pulling out of Toronto and sports teams are going to start refusing to come to Toronto." Fortunately, or unfortunately, within about two days, stuff like this started to happen. As a consequence, my editor saw me

as some sort of visionary. At the beginning of 2004, I came back to them to say that this big thing — avian flu — is coming, and I have to write about it. They really gave me a lot of leeway, and I credit them immensely.

Right now, the story is starting to wane. When I mentioned I really want to do this terrific story about how we know how effective the vaccine is, I am not getting the same reception to these ideas that I used to get. I don't know what the answer to this is, but I am very concerned that I'm not going to have the leeway that I've had, and other people won't, either.

McKenna: I experienced this same thing at my Atlanta paper. But since I've been writing the past couple of months more about businesses experience of a potential pandemic and their planning, there's a definite chill on the story at the same time that the private sector interest in preparing for a pandemic is ramping way up. By definition, most of that stuff that businesses are doing is happening behind the scenes, because it's competitive intelligence for them. DHL doesn't really want to talk about their planning in case they are doing it better than FedEx. The reverse may be true.

Christine Gorman, Time magazine: Journalists also have competitive issues, and we don't want to share sources. Just the idea of sharing your sources with other reporters within your own organization is enough to give you the willies. During a true pandemic situation, aren't we going to have to do some of this? And none of us is really prepared to do that.

Sipress: With the scenario in Indonesia, which is probably the closest parallel that we have, a lot of the other news organizations were our competitors. With the exception of the newspaper in New York, we ended up cooperating with everybody. During coverage of the tsunami, a couple of us were the first ones there, with only one taxi we could find. So it was The Washington Post, Financial Times, L.A. Times, and two other reporters and the driver in one taxi and we all filed our stories together. We filed essentially the same material, but our stories were all remarkably different because of what details we put in, what approach we took, whatever context we put in. I suspect you'll see the same thing happen when the pandemic comes out. And there aren't that many people who have taken this story all that seriously. Margie Mason always has been very generous with me when I tell her I'm coming to Vietnam. [See Mason's comments in referred article.] And I've done the same for other people who come to Indonesia. So I don't worry that much about it at this point.

Mason: Right now nobody asks me because I don't think any of them care, but if I go on vacation and somebody says, "Oh, by the way, could you leave your Rolodex open so that we could sort of pluck through your cards if we need cell phone numbers for those people at WHO?," I would be really reluctant to do that because of the relationship I have with those people, right?

Pope: I'm going to take out a position in the middle. Post-Katrina, and everyone has taken over everything, and I can't do all the public health stories. But I don't give out cell phone numbers. I don't tell people I have the cell phone numbers, but I give out office numbers, I'll give out names of folks, but I'm keeping the cell phone numbers to myself. When I go on vacation, if I see something coming up, I will say this might come up while I'm gone, here's the person to call. Again, Katrina taught us the value of collegiality.