If you want, call Dennis Wolff a prophet.

On Nov. 11, 2008 three days prior to the start of his 15th season as head coach of Boston University’s men’s basketball team, he said:

“I’m sure there are people who are saying this is an important year for Dennis Wolff as the coach at BU. I never personally look at it from that direction. There are some times you talk to people and you feel like the bottom has totally fallen out.”

The Terriers were picked to finish first in the America East Conference for the second-consecutive season two weeks prior to Wolff’s comments—a long way from the bottom.

It’s the beginning of the season and Wolff heads up the long, narrow staircase leading from BU’s locker room to Case Gymnasium that’s been tread on so frequently, it’s turned the color of day-old coffee grounds. Same consistency, too. Wolff makes this walk almost every day.

His lengthy fingers grip the red railing as he approaches a single door that opens to the vestibule. In it, there’s a dilapidated trophy case, a high school-esque snack bar and multiple entrances to the most important place he—or anyone involved with the program—has set foot since its opening in 1972.

At its peak during practice, Case Gym (nicknamed “The Roof” for its location above Walter Brown Arena) is a cacophony of squeaking shoes, clapping hands, baritone voices and the overriding sound of basketballs striking the tan hardwood made yellow by the industrial fluorescent lighting. In more subdued moments, the atmosphere can be equally gripping, whether an exhausted team is huddled at mid-court, an individual is refining his jumper or a janitor is sweeping the floor.

Taking strides slightly longer than the average gait, Wolff approaches a set of oak doors, pulls the handle and sees his team. They’re loose. Joking about new haircuts, laughing at awkward layups and, most importantly, excited about the upcoming season. After losing in the quarterfinals of the conference tournament for two consecutive years, a once juvenile group of players is primed for big things. Wolff knows this. He also knows he’s coached his way to three-straight losing seasons. And that he’s not the only one who’s noticed.

As Wolff directs drills, all the while switching rolled up play sheets back-and-forth between his right hand and shorts pocket, his intensity increases.

“Let’s go brother,” he yells to freshman forward Jeff Pelage. “You need to play way better. You need to realize what it takes to play at this level.”

Often, Wolff will deliver a rapid succession of “waits” or “whoas” to stop a drill in progress if it isn’t going well. Frustration following stoppage is evident on the players’ faces and even more visible when he reprimands them. His comments, ranging from encouraging to riddled with expletives, dance around the cavernous space every afternoon between 3-5:00 p.m. This is where Wolff has orchestrated championships. It’s where he’s molded immature kids into men.

It’s also where he’s lost 22 games in a season and what seems like as many players to transfer.

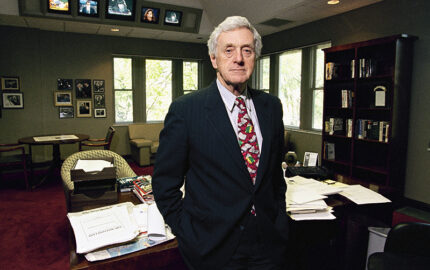

Wolff has never been known as a players coach. His inner-city New York upbringing and yearning for perfection wouldn’t allow it. Instead, his piercing blue eyes focus on every detail of the gameplay and with a stern stare he runs his team.

More than anything, Wolff deplores a lack of hustle. Like a shark that’s detected a teardrop of blood diffused in the ocean, when one of his players isn’t hustling, he strikes.

“He definitely gets on people, but it toughens you up and gets you ready for the real world,” says senior point guard Marques Johnson. “I’m not really afraid to face a new boss or anything like that. After going through a practice with coach Wolff, I can handle anybody.”

In 2005, Johnson’s freshman year, he approached Wolff with a problem. His ball handling skills were raw for the college game and his passing needed improvement. But that’s not what they discussed.

“I had just gotten to college and I was like, ‘How do I write a check?’”

After joking with Johnson about how he could have lasted 18 years in this world without scribbling xx/oo after a dollar amount, Wolff happy obliged his recruit’s request. Three years later, Johnson was named co-captain of one of Wolff’s most promising teams.

Check writing lessons aside, Wolff’s on-court style isn’t for everyone. While transfers occur at every college in America, his program has endured seven over a five-year period. Good players left too. Like Tony Gaffney, who averaged a double-double with 3.8 blocks per game this season at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Like sharp shooter Corey Hassan, who started all 28 games of his rookie season (2005-06) and finished second on the team in scoring. Like Will Creekmore, a wide-bodied rebounder who played just eight games before getting his release.

“I went to Boston as a pretty immature 18-year old and left with a lot of experience on how to handle authority, how to take criticism,” Creekmore, who now plays for Missouri State, says.

Perhaps, more than any factor that negatively impacts a program, transfers plunge it to the bottom. It’s like trading a player, but getting nothing in return. The question quickly became: Why are so many kids leaving a program that has achieved four-straight 20-win seasons and an NCAA Tournament appearances in 1997 and 2002?

“I’m pretty sure that the reason everyone I talked to transferred was because they didn’t get along with coach Wolff,” Hassan, now playing at Sacred Heart University, says. “I feel like people play best when they play with confidence and one of his biggest problems is that he gets on people so hard that they had no confidence.”

With a record of 5-7 the Terriers are preparing to face the University at Albany, in a season that’s promise has depleted quicker than an untied balloon, without three of their stars: Corey Lowe, Tyler Morris and Carlos Strong. Lowe is serving a one-game suspension for picking up two technical fouls the game prior and Morris and Strong are out for the season—ACL and meniscus. Injuries are nothing new to Wolff, but Morris and Strong are two of his top five scorers and veteran leaders.

BU’s in the game. Sophomore forward John Holland is on his way to a 25-point performance and the Terriers are playing inspired basketball at SEFCU Arena. They lead 61-57 with 39 seconds left in regulation—usually a safe cushion with a 35 second shot clock. But when a team’s been outscored 157-108 in its previous two losses, confidence isn’t exactly skyrocketing.

After a jumper and-1 by Albany’s Tim Ambrose, BU forward Scott Brittain turns the ball over on a sloppy inbounds play and fouls Ambrose, who sinks both shots to put Albany ahead. A desperation jumper by fifth-year senior Matt Wolff (Dennis’ son) that would have won the game doesn’t fall and the Terriers’ collapse is complete. It’s the type of breakdown Terrier fans have become accustomed to seeing.

“At the end of games we were so afraid to make plays because we thought we would lose that guys just stood around,” Morris, a redshirt junior co-captain, says. “And that was the problem. We got to that point and people wouldn’t make a play.”

Is the pressure Wolff places on his players so overbearing they can’t execute simple sets in crunch time? Or does the burden fall on the athletes to deliver?

“There are going to be players who respond well to being criticized or being yelled at, but some players respond to a different type of encouragement,” says senior walk-on Sam Tully. “I think the players he has now respond to being positively encouraged as opposed to being criticized. I don’t think he can adapt to that.”

Adaptation can be hard, especially when you’ve been in the business as long as Wolff. When you post the top scoring defense in the league seven years in a row, there doesn’t seem to be much need to run a free-flowing offense. That is, unless the Internet message boards are clamoring, the fans are unhappy and the administration starts to wonder.

In the current college basketball culture, it’s all about making the NCAA Tournament. That’s where the money is. That’s where the spectators are. That’s where the droves of office workers are using the Boss Button to hide their live video feeds of the latest first-round upset.

BU hasn’t gone dancing since 2002. Whether that’s too long is up for debate, but since Wolff’s first season, things have changed.

In the last five seasons, 33 mid-major schools have made the NCAA Tournament. That’s 10 percent of the teams that make the tournament, not to mention the other 344 squads vying for a shoutout on Selection Sunday.

In its 100-year history, BU’s appeared in the postseason six times. One-third of the school’s NCAA berths have been led by Wolff, who’s accumulated a 247-197 record in 15 years of coaching the Terriers.

“The life of a mid-major coach is very fragile because it’s so dog-gone difficult to get into the tournament,” says Western Carolina University coach Larry Hunter. “In one-bid conferences, you’re talking about injuries and illnesses that can affect the outcome of your season, being fortuitous in terms of guys hitting big baskets or making free throws.”

Hunter coached 12 years at Ohio University where he had a record of 208-148 but was fired in 2001 for his lack of postseason success. Hunter’s Bobcats had made just one tournament appearance and one NIT appearance in his 12 seasons.

Barry Hinson, the Director of External Relations at Kansas University, coached Missouri State University for nine seasons. In those nine years, he achieved RPIs (Ratings Percentage Index—a system the NCAA created in 1981 as an additional way to evaluate tournament hopefuls) as low as 35, 34 and 21 (the lower the better). By comparison, Brigham Young University had an RPI of 21 this season and lost to Texas A&M in the first round.

None of Hinson’s highly successful teams made the tournament, though, and on March 9, 2008 Missouri State Athletic Director Bill Rowe held a press conference announcing Hinson wouldn’t return. Now on the opposite side of the spectrum at KU, Hinson advocates for the little guys.

“Administrators don’t understand that at the mid-major level, it’s so cyclical. You can’t have the best recruiting class year-in and year-out. I don’t care if you’re at Boston U., you’re not beating Boston College,” Hinson says.

“Why should Boston University be a program that goes to the NCAA Tournament every year?” says Seth Greenberg, head coach at Virginia Tech. “I think you’re seeing it more and more—the impatience of administrations has become an epidemic.”

Where, then, does that leave Wolff and how patient has his administration been?

Observing Wolff on the sidelines during a game is like watching whack-a-mole. It’s always an unknown when he’ll pop up out of his seat to point cross-court or spit out commands. Then his knees bend and he’s back down, turning to an assistant coach to mutter something with his hand cupped over his mouth. Up again, this time he respectfully disagrees with an official’s call. Back down, his neck tie swinging side-to-side as he sits on his hands.

“I think he’s misunderstood in the public eye,” says former 2006-07 co-captain Brian Macon, a transfer from Miami Dade Community College. “Everyone sees him at the games when he’s screaming and looks like he’s going crazy, but he’s just coaching.”

Despite the vein-popping antics, Wolff’s received three technical fouls in his 444 games at BU.

“If you walk into the gym and heard him cursing somebody out, you’d probably think he does it all the time and maybe that’s how he got his bad rep,” Tully says. “But most of the time he’s a pretty level-headed guy.”

Winning is a cure-all.

Wolff has patrolled BU’s bench for those moments where everything’s blissful. Even the aftertaste of the Diet Coke he sips at every practice has a little extra palatability to it. The painted basketballs in his office prove as much.

Just as it had when his teams were expected to win 20 games and anything less was unacceptable, it’s going right again this year. BU’s won six games in a row for the first time since the 2003-04 season, including an instant classic quadruple overtime victory against Stony Brook.

Still, there’s an uneasy pressure surrounding most occurrences as the Terriers trudge through their 2008-09 campaign—one that gets magnified with every embarrassing loss and tossed aside with each gritty victory. It’s always the failures, though, that remove another strand of hair from Wolff’s nearly-bald head or add a wrinkle to his slender face.

Things didn’t used to be like that—the shadows of losing seasons wanting to creep into The Roof’s corners were left outside.

When the team was winning, Wolff could have taken offers at Atlantic 10 schools like Fordham and St. Bonaventure but he remained loyal. Sure first-round defeats in the conference tournament were upsetting, but the wins were there, elevating the credibility of a program.

The current Terriers are on the rise as well. The 2009 America East Rookie of the Year, Jake O’Brien says he’s gaining confidence by the practice and he feels like he’s able to play his game under Wolff. Workouts are unusually productive and the media are glowing but even after six-straight victories (during a winning streak that would swell to eight) fans still bash Wolff.

“In a strange way, the unfortunate injuries to Tyler Morris and Carlos Strong have meant that Dennis Wolff can’t use his stupid combinations and is less likely to over coach his way out of games,” says an anonymous commenter on a BU basketball blog.

Could anonymous truly believe the coach had no impact on an eight-game winning streak engineered without two of his top scorers?

Bad losses to Vermont, Binghamton and Stony Brook ended the streak. The message boards sang.

Wolff could do no right.

Orono, Maine is a distant place. While none of the schools in the America East Conference (save BU) are located in a particularly metropolitan community, the sheer utterance of the word Maine conjures up images of being able to see your own breath in Alfond Arena not only for hockey, but basketball too.

Here, the Terriers literally and metaphorically limped off the bus after a 13-point loss to Vermont midway through the 2007-08 season—a season in which, again, BU is underachieving.

Co-captains Tyler Morris and Matt Wolff feel the need to step in, so they call a players-only meeting in Morris’ room at the Fairfield Inn by Marriott Bangor. The 13 young men shuffle into the dimly lit double and find spots on the bed, along the walls or in uncomfortable chairs. By far, this is the worst hotel the team stays at, but there are more pressing issues than five-star ratings at hand.

Matt Wolff, a spitting image of his father, only with hair, addresses the team.

“It’s been difficult for me to sit on the sidelines with the injuries I’ve had over the last two seasons. I used to sit there watching and feel more a part of the losses than the wins. Now that I’m playing this season and I’m healthy, I realize how meaningful this opportunity is,” he says.

Sam Tully, who doesn’t usually speak at meetings like this, felt the urge.

“Make the most of your time in college because before you know it, it’s going to be done,” he says.

What the majority of players in the room didn’t know—and what Tully would go on to tell them—is that Tully’s father passed away before he transferred out of Suffolk University. Tully promised his dad he’d make the basketball team at BU.

“That sort of story puts everything in perspective. If he can deal with that, why can’t we play together and do it for each other?” Morris says. “We basically decided that we wanted to play for our teammates. Not our coaches, not the fans, not the media, we were playing for the happiness of us.”

“People realized that we sometimes get too worked up about what coach Wolff was saying and we got down on ourselves,” Tully says.

That’s when the culture surrounding the team started to morph. That’s when work became play. That’s when Wolff started to lose his grip. The same one that clenches that red railing in a narrow staircase leading toward Case Gymnasium.

The Terriers won eight of their next nine games.

Entering his junior season, former Terrier Rashad Bell thought he was “the shit.” He averaged 12 points per game and 5.2 rebounds per game his sophomore year (2002-03). From the moment a visibly nervous Wolff visited Bell’s apartment in a less-safe section of Queens, he knew the 6-foot-8 athletic specimen could succeed at BU.

Despite Bell’s realization that he should dominate the conference, his work ethic deteriorated. So did his game. What could have been an All-Conference caliber season ended with no awards and no America East Championship.

Then came the meetings. No brutality, just encouragement from Wolff, who informed Bell he could make money professionally if he changed his attitude. That simple statement was a turning point for Bell, who finished his four-year playing career ninth on BU’s all-time scoring list. Emphasis on that four-year part.

“Without [Wolff], I definitely wouldn’t have graduated,” Bell says. “He wanted to make sure all his players gradated on time during his tenure.”

Bell—who’s currently playing for Albacomp in Hungary in his fourth season overseas—isn’t the only one who’s benefitted from Wolff’s emphasis on academics. Using the most current data released by the NCAA, Wolff’s Graduation Success Rate (GSR) is 100. The Division I average is 62. That means of the student-athletes who played under Wolff or transferred into the school, all of them graduated.

The only McDonald’s All American to play for the Terriers, Joey Beard, transferred to BU from Duke University after a falling out with legendary coach Mike Krzyzewski. The reason?

“I came to BU because of [Wolff] and the relationship we established when I was in high school,” Beard says.

Beard, who now plays for AJ Milano in the Euroleague, called Wolff for advice after getting his release from Duke.

“You’ve just got to be happy,” Wolff says to Beard. “Sometimes the biggest school isn’t going to be the best school for you. You might want to think about going somewhere that you’re comfortable with as a school and a basketball program.”

That phone call motivated Beard to look at schools rather than basketball programs and he graduated BU with a degree from the College of Communication and an America East Academic Honor Roll award. Under Wolff, 21 players have made the honor roll.

Wolff does his best to keep in touch with former players and many reach out to him. Collins even invited him to his wedding.

“I’ve been back to BU every year since I left and it’s always good to see coach Wolff,” says Stijn Dhondt, who hit a memorable game-winning buzzer-beater in the semifinals of the 2002 America East Tournament. “He was always asking about my parents and my family, so I really appreciated that.”

Head coach Ryan Butt oversees a layup drill at Mountville High School in Mount Troy, Pa. He used to be on the other side, effortlessly laying the ball off the backboard and into the hoop, maybe having it roll out every once in 100 attempts and having to do pushups as a result.

Butt, another former captain on a Wolff-coached team, speaks of Wolff the way most in the coaching business do—with respect.

“As a player, did I always see eye-to-eye with him? No. But now I understand that from a coach’s perspective,” says Butt, who’s adapted some of the drills he ran at BU as well as a defense-first philosophy from his time in college.

In a decade and a half of coaching, you develop a unique style to lift your team from the bottom. A way you want things done that others will find difficult to duplicate. It’s an increasingly challenging task in the current format of college basketball, one that’s worn on Wolff’s broad yet boney shoulders. It’s also a task that doesn’t go unnoticed.

“I think he’s excellent at managing people, especially the most important people—the young people,” says University of Notre Dame coach Mike Brey. “He makes a man out of young people who come through his program. If my son [Kyle] didn’t play football at Buffalo, I’d want him playing basketball for Dennis Wolff.”

SEFCU Arena in Albany, N.Y., is the site of the 2009 America East Tournament. The third-seeded Terriers defeated the sixth-seeded University of Maryland-Baltimore County twice during the regular season and are poised to do so again. That is, until another collapse. This time, they surrender an eight-point lead with 3:13 left in regulation.

Emotions are raw following the first-round upset, forcing BU’s toughest players to tears as the final buzzer sounds. Wolff, however, walks off the court in the same manner he had for the other 443 contests of his BU career—that slightly extended gait propelling him to the locker room ahead of everyone else. The Terriers finish the season 17-13.

Wolff’s no stranger to addressing the media after a first-round tournament loss. This will be the sixth time he’s done it in his career. And while his press conference demeanor rarely changes despite the game’s result, this time something was off. Usually, win-or-lose, he’s acknowledged by BU’s brass. Mainly Assistant Vice President and Director of Athletics Mike Lynch. But upon entering the glorified racquetball court/press conference room, Wolff didn’t receive a glance, let alone a handshake.

Two days after the loss, Wolff began preparation for next season with a recruiting trip to New York. Then his Blackberry rang.

“Dennis, would you be able to come back to Boston tomorrow?” Lynch asked.

Wolff immediately knew why.

“Mike, am I getting let go?”

“I’d rather not talk about this over the phone, can you come back?”

In a meeting on March 11, 2009 between Wolff, Lynch and Executive Director of Athletics and men’s hockey coach Jack Parker, Wolff is asked to resign. When he refuses, they fire him.

That day, Wolff receives more than 100 phone calls from friends, relatives and opposing coaches and almost all of their comments can be summed up with one word: shocked.

“I had hoped to be able to end my career at BU,” Wolff says. “That’s the nature of the business. I guess in the scheme of things, to be fortunate enough to live in one place and coach one team for 15 years is a good thing.”

Wolff won’t get a chance to lead what is arguably the best recruiting class in BU history. He won’t get to stand next to Corey Lowe, one of the Terriers’ best-ever players to honor him on Senior Day. He won’t get to experience the exhilaration of slowly snipping at the nylon until that final piece of net slides out of its orange metallic support and gets raised in jubilation. He won’t even get to make that trek up the coffee-colored stairs at Case Gymnasium ever again.

The bottom has fallen out.

On Nov. 11, 2008 three days prior to the start of his 15th season as head coach of Boston University’s men’s basketball team, he said:

“I’m sure there are people who are saying this is an important year for Dennis Wolff as the coach at BU. I never personally look at it from that direction. There are some times you talk to people and you feel like the bottom has totally fallen out.”

The Terriers were picked to finish first in the America East Conference for the second-consecutive season two weeks prior to Wolff’s comments—a long way from the bottom.

It’s the beginning of the season and Wolff heads up the long, narrow staircase leading from BU’s locker room to Case Gymnasium that’s been tread on so frequently, it’s turned the color of day-old coffee grounds. Same consistency, too. Wolff makes this walk almost every day.

His lengthy fingers grip the red railing as he approaches a single door that opens to the vestibule. In it, there’s a dilapidated trophy case, a high school-esque snack bar and multiple entrances to the most important place he—or anyone involved with the program—has set foot since its opening in 1972.

At its peak during practice, Case Gym (nicknamed “The Roof” for its location above Walter Brown Arena) is a cacophony of squeaking shoes, clapping hands, baritone voices and the overriding sound of basketballs striking the tan hardwood made yellow by the industrial fluorescent lighting. In more subdued moments, the atmosphere can be equally gripping, whether an exhausted team is huddled at mid-court, an individual is refining his jumper or a janitor is sweeping the floor.

Taking strides slightly longer than the average gait, Wolff approaches a set of oak doors, pulls the handle and sees his team. They’re loose. Joking about new haircuts, laughing at awkward layups and, most importantly, excited about the upcoming season. After losing in the quarterfinals of the conference tournament for two consecutive years, a once juvenile group of players is primed for big things. Wolff knows this. He also knows he’s coached his way to three-straight losing seasons. And that he’s not the only one who’s noticed.

As Wolff directs drills, all the while switching rolled up play sheets back-and-forth between his right hand and shorts pocket, his intensity increases.

“Let’s go brother,” he yells to freshman forward Jeff Pelage. “You need to play way better. You need to realize what it takes to play at this level.”

Often, Wolff will deliver a rapid succession of “waits” or “whoas” to stop a drill in progress if it isn’t going well. Frustration following stoppage is evident on the players’ faces and even more visible when he reprimands them. His comments, ranging from encouraging to riddled with expletives, dance around the cavernous space every afternoon between 3-5:00 p.m. This is where Wolff has orchestrated championships. It’s where he’s molded immature kids into men.

It’s also where he’s lost 22 games in a season and what seems like as many players to transfer.

Wolff has never been known as a players coach. His inner-city New York upbringing and yearning for perfection wouldn’t allow it. Instead, his piercing blue eyes focus on every detail of the gameplay and with a stern stare he runs his team.

More than anything, Wolff deplores a lack of hustle. Like a shark that’s detected a teardrop of blood diffused in the ocean, when one of his players isn’t hustling, he strikes.

“He definitely gets on people, but it toughens you up and gets you ready for the real world,” says senior point guard Marques Johnson. “I’m not really afraid to face a new boss or anything like that. After going through a practice with coach Wolff, I can handle anybody.”

In 2005, Johnson’s freshman year, he approached Wolff with a problem. His ball handling skills were raw for the college game and his passing needed improvement. But that’s not what they discussed.

“I had just gotten to college and I was like, ‘How do I write a check?’”

After joking with Johnson about how he could have lasted 18 years in this world without scribbling xx/oo after a dollar amount, Wolff happy obliged his recruit’s request. Three years later, Johnson was named co-captain of one of Wolff’s most promising teams.

Check writing lessons aside, Wolff’s on-court style isn’t for everyone. While transfers occur at every college in America, his program has endured seven over a five-year period. Good players left too. Like Tony Gaffney, who averaged a double-double with 3.8 blocks per game this season at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Like sharp shooter Corey Hassan, who started all 28 games of his rookie season (2005-06) and finished second on the team in scoring. Like Will Creekmore, a wide-bodied rebounder who played just eight games before getting his release.

“I went to Boston as a pretty immature 18-year old and left with a lot of experience on how to handle authority, how to take criticism,” Creekmore, who now plays for Missouri State, says.

Perhaps, more than any factor that negatively impacts a program, transfers plunge it to the bottom. It’s like trading a player, but getting nothing in return. The question quickly became: Why are so many kids leaving a program that has achieved four-straight 20-win seasons and an NCAA Tournament appearances in 1997 and 2002?

“I’m pretty sure that the reason everyone I talked to transferred was because they didn’t get along with coach Wolff,” Hassan, now playing at Sacred Heart University, says. “I feel like people play best when they play with confidence and one of his biggest problems is that he gets on people so hard that they had no confidence.”

With a record of 5-7 the Terriers are preparing to face the University at Albany, in a season that’s promise has depleted quicker than an untied balloon, without three of their stars: Corey Lowe, Tyler Morris and Carlos Strong. Lowe is serving a one-game suspension for picking up two technical fouls the game prior and Morris and Strong are out for the season—ACL and meniscus. Injuries are nothing new to Wolff, but Morris and Strong are two of his top five scorers and veteran leaders.

BU’s in the game. Sophomore forward John Holland is on his way to a 25-point performance and the Terriers are playing inspired basketball at SEFCU Arena. They lead 61-57 with 39 seconds left in regulation—usually a safe cushion with a 35 second shot clock. But when a team’s been outscored 157-108 in its previous two losses, confidence isn’t exactly skyrocketing.

After a jumper and-1 by Albany’s Tim Ambrose, BU forward Scott Brittain turns the ball over on a sloppy inbounds play and fouls Ambrose, who sinks both shots to put Albany ahead. A desperation jumper by fifth-year senior Matt Wolff (Dennis’ son) that would have won the game doesn’t fall and the Terriers’ collapse is complete. It’s the type of breakdown Terrier fans have become accustomed to seeing.

“At the end of games we were so afraid to make plays because we thought we would lose that guys just stood around,” Morris, a redshirt junior co-captain, says. “And that was the problem. We got to that point and people wouldn’t make a play.”

Is the pressure Wolff places on his players so overbearing they can’t execute simple sets in crunch time? Or does the burden fall on the athletes to deliver?

“There are going to be players who respond well to being criticized or being yelled at, but some players respond to a different type of encouragement,” says senior walk-on Sam Tully. “I think the players he has now respond to being positively encouraged as opposed to being criticized. I don’t think he can adapt to that.”

Adaptation can be hard, especially when you’ve been in the business as long as Wolff. When you post the top scoring defense in the league seven years in a row, there doesn’t seem to be much need to run a free-flowing offense. That is, unless the Internet message boards are clamoring, the fans are unhappy and the administration starts to wonder.

In the current college basketball culture, it’s all about making the NCAA Tournament. That’s where the money is. That’s where the spectators are. That’s where the droves of office workers are using the Boss Button to hide their live video feeds of the latest first-round upset.

BU hasn’t gone dancing since 2002. Whether that’s too long is up for debate, but since Wolff’s first season, things have changed.

In the last five seasons, 33 mid-major schools have made the NCAA Tournament. That’s 10 percent of the teams that make the tournament, not to mention the other 344 squads vying for a shoutout on Selection Sunday.

In its 100-year history, BU’s appeared in the postseason six times. One-third of the school’s NCAA berths have been led by Wolff, who’s accumulated a 247-197 record in 15 years of coaching the Terriers.

“The life of a mid-major coach is very fragile because it’s so dog-gone difficult to get into the tournament,” says Western Carolina University coach Larry Hunter. “In one-bid conferences, you’re talking about injuries and illnesses that can affect the outcome of your season, being fortuitous in terms of guys hitting big baskets or making free throws.”

Hunter coached 12 years at Ohio University where he had a record of 208-148 but was fired in 2001 for his lack of postseason success. Hunter’s Bobcats had made just one tournament appearance and one NIT appearance in his 12 seasons.

Barry Hinson, the Director of External Relations at Kansas University, coached Missouri State University for nine seasons. In those nine years, he achieved RPIs (Ratings Percentage Index—a system the NCAA created in 1981 as an additional way to evaluate tournament hopefuls) as low as 35, 34 and 21 (the lower the better). By comparison, Brigham Young University had an RPI of 21 this season and lost to Texas A&M in the first round.

None of Hinson’s highly successful teams made the tournament, though, and on March 9, 2008 Missouri State Athletic Director Bill Rowe held a press conference announcing Hinson wouldn’t return. Now on the opposite side of the spectrum at KU, Hinson advocates for the little guys.

“Administrators don’t understand that at the mid-major level, it’s so cyclical. You can’t have the best recruiting class year-in and year-out. I don’t care if you’re at Boston U., you’re not beating Boston College,” Hinson says.

“Why should Boston University be a program that goes to the NCAA Tournament every year?” says Seth Greenberg, head coach at Virginia Tech. “I think you’re seeing it more and more—the impatience of administrations has become an epidemic.”

Where, then, does that leave Wolff and how patient has his administration been?

Observing Wolff on the sidelines during a game is like watching whack-a-mole. It’s always an unknown when he’ll pop up out of his seat to point cross-court or spit out commands. Then his knees bend and he’s back down, turning to an assistant coach to mutter something with his hand cupped over his mouth. Up again, this time he respectfully disagrees with an official’s call. Back down, his neck tie swinging side-to-side as he sits on his hands.

“I think he’s misunderstood in the public eye,” says former 2006-07 co-captain Brian Macon, a transfer from Miami Dade Community College. “Everyone sees him at the games when he’s screaming and looks like he’s going crazy, but he’s just coaching.”

Despite the vein-popping antics, Wolff’s received three technical fouls in his 444 games at BU.

“If you walk into the gym and heard him cursing somebody out, you’d probably think he does it all the time and maybe that’s how he got his bad rep,” Tully says. “But most of the time he’s a pretty level-headed guy.”

Winning is a cure-all.

Wolff has patrolled BU’s bench for those moments where everything’s blissful. Even the aftertaste of the Diet Coke he sips at every practice has a little extra palatability to it. The painted basketballs in his office prove as much.

Just as it had when his teams were expected to win 20 games and anything less was unacceptable, it’s going right again this year. BU’s won six games in a row for the first time since the 2003-04 season, including an instant classic quadruple overtime victory against Stony Brook.

Still, there’s an uneasy pressure surrounding most occurrences as the Terriers trudge through their 2008-09 campaign—one that gets magnified with every embarrassing loss and tossed aside with each gritty victory. It’s always the failures, though, that remove another strand of hair from Wolff’s nearly-bald head or add a wrinkle to his slender face.

Things didn’t used to be like that—the shadows of losing seasons wanting to creep into The Roof’s corners were left outside.

When the team was winning, Wolff could have taken offers at Atlantic 10 schools like Fordham and St. Bonaventure but he remained loyal. Sure first-round defeats in the conference tournament were upsetting, but the wins were there, elevating the credibility of a program.

The current Terriers are on the rise as well. The 2009 America East Rookie of the Year, Jake O’Brien says he’s gaining confidence by the practice and he feels like he’s able to play his game under Wolff. Workouts are unusually productive and the media are glowing but even after six-straight victories (during a winning streak that would swell to eight) fans still bash Wolff.

“In a strange way, the unfortunate injuries to Tyler Morris and Carlos Strong have meant that Dennis Wolff can’t use his stupid combinations and is less likely to over coach his way out of games,” says an anonymous commenter on a BU basketball blog.

Could anonymous truly believe the coach had no impact on an eight-game winning streak engineered without two of his top scorers?

Bad losses to Vermont, Binghamton and Stony Brook ended the streak. The message boards sang.

Wolff could do no right.

Orono, Maine is a distant place. While none of the schools in the America East Conference (save BU) are located in a particularly metropolitan community, the sheer utterance of the word Maine conjures up images of being able to see your own breath in Alfond Arena not only for hockey, but basketball too.

Here, the Terriers literally and metaphorically limped off the bus after a 13-point loss to Vermont midway through the 2007-08 season—a season in which, again, BU is underachieving.

Co-captains Tyler Morris and Matt Wolff feel the need to step in, so they call a players-only meeting in Morris’ room at the Fairfield Inn by Marriott Bangor. The 13 young men shuffle into the dimly lit double and find spots on the bed, along the walls or in uncomfortable chairs. By far, this is the worst hotel the team stays at, but there are more pressing issues than five-star ratings at hand.

Matt Wolff, a spitting image of his father, only with hair, addresses the team.

“It’s been difficult for me to sit on the sidelines with the injuries I’ve had over the last two seasons. I used to sit there watching and feel more a part of the losses than the wins. Now that I’m playing this season and I’m healthy, I realize how meaningful this opportunity is,” he says.

Sam Tully, who doesn’t usually speak at meetings like this, felt the urge.

“Make the most of your time in college because before you know it, it’s going to be done,” he says.

What the majority of players in the room didn’t know—and what Tully would go on to tell them—is that Tully’s father passed away before he transferred out of Suffolk University. Tully promised his dad he’d make the basketball team at BU.

“That sort of story puts everything in perspective. If he can deal with that, why can’t we play together and do it for each other?” Morris says. “We basically decided that we wanted to play for our teammates. Not our coaches, not the fans, not the media, we were playing for the happiness of us.”

“People realized that we sometimes get too worked up about what coach Wolff was saying and we got down on ourselves,” Tully says.

That’s when the culture surrounding the team started to morph. That’s when work became play. That’s when Wolff started to lose his grip. The same one that clenches that red railing in a narrow staircase leading toward Case Gymnasium.

The Terriers won eight of their next nine games.

Entering his junior season, former Terrier Rashad Bell thought he was “the shit.” He averaged 12 points per game and 5.2 rebounds per game his sophomore year (2002-03). From the moment a visibly nervous Wolff visited Bell’s apartment in a less-safe section of Queens, he knew the 6-foot-8 athletic specimen could succeed at BU.

Despite Bell’s realization that he should dominate the conference, his work ethic deteriorated. So did his game. What could have been an All-Conference caliber season ended with no awards and no America East Championship.

Then came the meetings. No brutality, just encouragement from Wolff, who informed Bell he could make money professionally if he changed his attitude. That simple statement was a turning point for Bell, who finished his four-year playing career ninth on BU’s all-time scoring list. Emphasis on that four-year part.

“Without [Wolff], I definitely wouldn’t have graduated,” Bell says. “He wanted to make sure all his players gradated on time during his tenure.”

Bell—who’s currently playing for Albacomp in Hungary in his fourth season overseas—isn’t the only one who’s benefitted from Wolff’s emphasis on academics. Using the most current data released by the NCAA, Wolff’s Graduation Success Rate (GSR) is 100. The Division I average is 62. That means of the student-athletes who played under Wolff or transferred into the school, all of them graduated.

The only McDonald’s All American to play for the Terriers, Joey Beard, transferred to BU from Duke University after a falling out with legendary coach Mike Krzyzewski. The reason?

“I came to BU because of [Wolff] and the relationship we established when I was in high school,” Beard says.

Beard, who now plays for AJ Milano in the Euroleague, called Wolff for advice after getting his release from Duke.

“You’ve just got to be happy,” Wolff says to Beard. “Sometimes the biggest school isn’t going to be the best school for you. You might want to think about going somewhere that you’re comfortable with as a school and a basketball program.”

That phone call motivated Beard to look at schools rather than basketball programs and he graduated BU with a degree from the College of Communication and an America East Academic Honor Roll award. Under Wolff, 21 players have made the honor roll.

Wolff does his best to keep in touch with former players and many reach out to him. Collins even invited him to his wedding.

“I’ve been back to BU every year since I left and it’s always good to see coach Wolff,” says Stijn Dhondt, who hit a memorable game-winning buzzer-beater in the semifinals of the 2002 America East Tournament. “He was always asking about my parents and my family, so I really appreciated that.”

Head coach Ryan Butt oversees a layup drill at Mountville High School in Mount Troy, Pa. He used to be on the other side, effortlessly laying the ball off the backboard and into the hoop, maybe having it roll out every once in 100 attempts and having to do pushups as a result.

Butt, another former captain on a Wolff-coached team, speaks of Wolff the way most in the coaching business do—with respect.

“As a player, did I always see eye-to-eye with him? No. But now I understand that from a coach’s perspective,” says Butt, who’s adapted some of the drills he ran at BU as well as a defense-first philosophy from his time in college.

In a decade and a half of coaching, you develop a unique style to lift your team from the bottom. A way you want things done that others will find difficult to duplicate. It’s an increasingly challenging task in the current format of college basketball, one that’s worn on Wolff’s broad yet boney shoulders. It’s also a task that doesn’t go unnoticed.

“I think he’s excellent at managing people, especially the most important people—the young people,” says University of Notre Dame coach Mike Brey. “He makes a man out of young people who come through his program. If my son [Kyle] didn’t play football at Buffalo, I’d want him playing basketball for Dennis Wolff.”

SEFCU Arena in Albany, N.Y., is the site of the 2009 America East Tournament. The third-seeded Terriers defeated the sixth-seeded University of Maryland-Baltimore County twice during the regular season and are poised to do so again. That is, until another collapse. This time, they surrender an eight-point lead with 3:13 left in regulation.

Emotions are raw following the first-round upset, forcing BU’s toughest players to tears as the final buzzer sounds. Wolff, however, walks off the court in the same manner he had for the other 443 contests of his BU career—that slightly extended gait propelling him to the locker room ahead of everyone else. The Terriers finish the season 17-13.

Wolff’s no stranger to addressing the media after a first-round tournament loss. This will be the sixth time he’s done it in his career. And while his press conference demeanor rarely changes despite the game’s result, this time something was off. Usually, win-or-lose, he’s acknowledged by BU’s brass. Mainly Assistant Vice President and Director of Athletics Mike Lynch. But upon entering the glorified racquetball court/press conference room, Wolff didn’t receive a glance, let alone a handshake.

Two days after the loss, Wolff began preparation for next season with a recruiting trip to New York. Then his Blackberry rang.

“Dennis, would you be able to come back to Boston tomorrow?” Lynch asked.

Wolff immediately knew why.

“Mike, am I getting let go?”

“I’d rather not talk about this over the phone, can you come back?”

In a meeting on March 11, 2009 between Wolff, Lynch and Executive Director of Athletics and men’s hockey coach Jack Parker, Wolff is asked to resign. When he refuses, they fire him.

That day, Wolff receives more than 100 phone calls from friends, relatives and opposing coaches and almost all of their comments can be summed up with one word: shocked.

“I had hoped to be able to end my career at BU,” Wolff says. “That’s the nature of the business. I guess in the scheme of things, to be fortunate enough to live in one place and coach one team for 15 years is a good thing.”

Wolff won’t get a chance to lead what is arguably the best recruiting class in BU history. He won’t get to stand next to Corey Lowe, one of the Terriers’ best-ever players to honor him on Senior Day. He won’t get to experience the exhilaration of slowly snipping at the nylon until that final piece of net slides out of its orange metallic support and gets raised in jubilation. He won’t even get to make that trek up the coffee-colored stairs at Case Gymnasium ever again.

The bottom has fallen out.