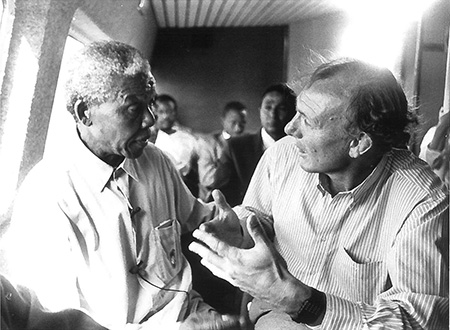

Richard Steyn, NF ’86, editor of The Star, was granted a one-on-one interview with Nelson Mandela during his first trip back to Robben Island after his release from prison. Photo courtesy of Richard Steyn

As editor in chief of Johannesburg’s The Star—at the time of Mandela’s release South Africa’s largest daily newspaper—I had the good fortune to meet him on many occasions, some social, some formal, of which a few stand out in my memory.

Our first meeting was at the Carlton Hotel when, soon after his release from prison, he came to be introduced and speak to the country’s newspaper editors. My immediate impression as he entered the room was of his commanding physical presence, large hands, and flashing smile. For 27 years we had wondered what the world’s most famous prisoner looked like; we had seen pictures of him on television and in our own newspapers; now he was actually with us in the flesh. Even the ranks of apartheid-supporting editors among us, who had spent decades demonizing Mandela, could scarce forbear to cheer.

* * *

Not long after that, former Rand Daily Mail editor Raymond Louw and I took Madiba (the clan name by which he became known) to breakfast at the Rand Club, an old colonial landmark in the center of Johannesburg not far from the headquarters of the African National Congress. Ray and I were South Africa representatives on the International Press Institute (IPI) board and Mandiba was due to be the keynote speaker at its 1994 world assembly in Kyoto, Japan. We thought some background on the activities of the IPI might be helpful to him.

He arrived at the Club, with two bodyguards, promptly at 8:30 a.m. (Punctuality is not a South African virtue.) In the imposing entrance hall, he stared around wide-eyed. “You know, this is the first time I’ve ever been inside the Rand Club,” he said. “As a young man [when he clerked for a white attorney], I used to deliver letters here on my bicycle.”

Our breakfast was on the first floor of the Club, and required us to climb up the lobby’s imposing central staircase. On the landing at the top of the stairs was Annigoni’s famous portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, which he paused briefly to admire.

Some years later, by which stage Madiba had been a guest-of-honor at the Rand Club, the central core of the building—including the prized Annigoni—was destroyed by fire. At great expense, the building was carefully and loving restored—except in one respect. At the top of the staircase, there is now a large portrait of Nelson Mandela. A reproduction of Annigoni’s Queen Elizabeth has been moved to an adjoining alcove.

In Kyoto, Ray Louw and I were asked by the IPI to welcome Madiba and his entourage when they arrived at the conference hotel, which we duly did, to be greeted like old friends. That afternoon, we took a stroll with Madiba through the lovely public park adjoining the hotel. The park was full of Japanese schoolchildren. I still remember the wide-eyed looks on their young faces, and their excitement, as it dawned on them that the elderly African man walking toward them was none other than Nelson Mandela.

* * *

Kenneth Kaunda, president of Zambia, had been kind enough to entertain, at his residence, a group of liberal white South Africans who had travelled to Lusaka to meet the ANC in exile. So when he came to South Africa shortly before the 1994 election, I thought I’d return the compliment and invite him to Sunday lunch at our home. Also there were Frank Ferrari of the African-American Institute, Helen Suzman, 1980 Nieman Fellow and Sowetan editor Aggrey Klaaste, and some of my Star colleagues. On the off chance, I also invited Madiba via his personal assistant, Barbara Masikela, and to our surprise and pleasure, he came.

My three young boys helped to serve the guests at table, and a convivial time was had by all. (Afterward, we posed for a family photograph with Madiba and President Kaunda which has since become a treasured memento.) At the lunch, Madiba made a memorable observation, leaning over to Kaunda and saying, “You know, KK, we [the ANC in exile] criticized you for trying to open a dialogue with the apartheid government; but you have been proved right, and we were wrong.”

* * *

I was one of a group of newspaper people invited to accompany Madiba on his first trip back to Robben Island since his release from prison. On the ferry over, I was given the opportunity of having a one-on-one discussion with Madiba for part of the way. As a former Capetonian for whom Robben Island had been out of bounds for my entire life, to be able to view Table Mountain from the quarry in which Madiba labored, and then to accompany him into his old prison cell and listen to some of his reminiscences, was a once-in-a lifetime experience. It reminded me how fortunate I was to be in journalism at that time in our country’s history.

* * *

Madiba was a master in his handling of the media. Every now and again, he would telephone me at home, to draw my attention to a report he was unhappy about or disagreed with. He never threatened or insisted on a correction, he simply wanted me to know how he felt, and left it at that.

In September 1992, South Africa was going through a dark period. The ANC had broken off negotiations with the government following allegations of official involvement in the massacres at Bisho and Boipatong, and the transition was on a knife edge. Early one Sunday morning, my phone rang. It was Madiba. Always formal, “Mr. Steyn,” he said, “why have the media not taken any notice of the speech I made in the Eastern Cape [I think it was] yesterday?” I had no idea what he was referring to, but sensed he had something to get off his chest. “Can I come and see you?” I asked. I roused our political editor, Shaun Johnson, and the two of us hurried over to the residence in Houghton, where a serious-faced Mandela sat us down and gave us probably the longest interview he had given to a South African newspaper since his release.

To “save the country from disaster,” he said, the ANC was prepared to restart negotiations without requiring further concessions from the government. He was ready to accept an undertaking in good faith from “Mr. de Klerk” on the critical issues of violence, political prisoners, and dangerous weapons, “in order to get South Africa out of the quagmire.” If the summit he was proposing went ahead, the move made by Mr. de Klerk and himself could “save the country from disaster.” He then went on to set out his views on a number of other matters of concern to the country.

The Star’s front page next day was headed “Mandela’s Olive Branch” and its op-ed page declared “We Must Pull SA From Quagmire.” Harvey Tyson in his book “Editors Under Fire,” takes up the story: “Once published, the interview reverberated around South Africa, and the world. It dominated headlines, was included in diplomatic bags … and gained the extraordinary distinction of being carried around by senior officials of the ANC and the government simultaneously.”

Our interview was spread across the table at de Klerk’s next Cabinet meeting, and the president grasped his opportunity. He wrote to Mandela as follows: “In the spirit of reconciliation and concern which was evident from your recent interview with The Star, I appeal to you once again to ensure that we can meet as soon as possible to discuss the pressing problems of our country. We owe it to the cause of peace and to all the citizens of South Africa.”

De Klerk may have been president, but it was Mandela who held the trump cards and he had once again played them (and us) with consummate skill. Negotiations between the two sides were resumed soon afterwards, and the rest—as they say—is history.