"In exile, the only house is that of writing." Theodor Adorno, the German philosopher and critic, conceived that metaphor. I encountered it in a book I was reviewing, and I decided to use the words, translated from German, as a tagline for my website. Full disclosure: except for the nine words that begin this essay, I have never read any Adorno. I hear his prose is difficult. Yet these particular words of his made perfect, intuitive sense to me. I know I can't really compare his exile, that of a Jewish merchant's son from Nazi Germany in the 1930's, to the rootlessness I was feeling at the time. Still, I identified, deeply.

What am I an exile from? I come from an immigrant family, twice over. But immigration is not the same thing as exile. As any Cuban will tell you, exile involves a dream of return to your homeland—one you were forced to leave. It's a matter for debate whether my family had to leave Guyana in 1981. I didn't have a say, in any case. I was only 6.

But when I left The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2007, I truly had no choice, being one reporter among many dozens laid off by a new corporate owner. Suddenly I was an exile from a newsroom, part of an early wave replenished many times over as the entire newspaper industry entered crisis mode.

I was among the fortunate few. A few months after my layoff, I was selected as a Nieman Fellow. For a time, this gave me shelter, a nice one as far as shelters go—warm, well stocked, even kind of glamorous, and the companionship of fellow travelers. But like all shelters, it was temporary. As spring arrived, I surveyed the job market, then decided that instead of re-entering an industry in serious upheaval I would pursue a book project. With half of my Nieman stipend saved, I set off for England to dig in archives for a story I wasn't sure I would find well documented enough to tell.

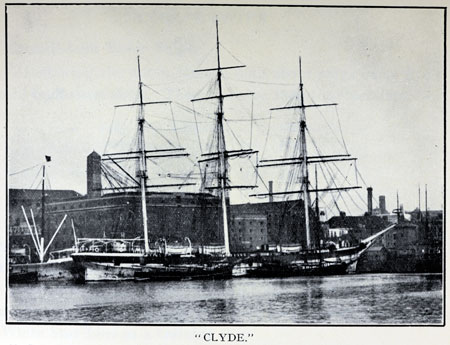

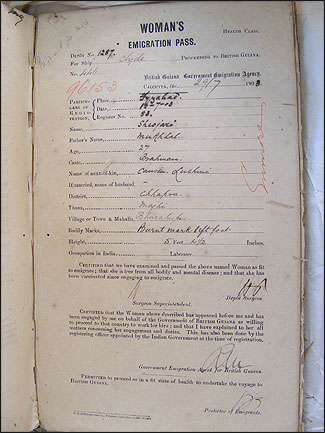

I wanted to write nonfiction exploring the mystery of my great-grandmother, who left Calcutta, pregnant and without a husband, to work on a Guyanese plantation in 1903. The details of her exit from India, with their hint of trauma or scandal, were not unique. Her story was the story of hundreds of thousands of Indian women who ended up in British colonies worldwide as indentured servants, semi-forced laborers who replaced slaves on sugar estates. Talk about exile. These women knew exile.

Getting Started

The journey I was about to embark on was nowhere close to theirs in daring or sacrifice.

During my Nieman winter break, I had made some forays into the British Colonial Office archives in London and then to India to ensure the story was substantial enough to take a risk. It was. I didn't, however, realize how great the risk would seem to the publishing industry, then facing its own crisis.

It took more than a year for my book proposal to sell. Five editors at five houses liked the proposal well enough to pitch it to acquisition boards. Others said they liked it, but didn't bother to pitch. The consensus seemed to be that the story wasn't commercial enough for anyone to take a chance on during what turned out to be the start of publishing's crisis years. An editor at a major trade house complimented me and the subject matter, saying it was "a story well worth telling, a story well worth hearing." But she concluded: "I'm sad to say I found very few problems with the proposal and the story itself—my only worry is more on our end, how we'd bring this to a big enough audience."

Another rejection letter read:

We ultimately felt that, while an engaging, global and beautifully written memoir, the audience for this would be small and difficult to reach … We all loved her writing, though … and would love to see her pursue a bigger story or subject in the future.

When my proposal was on the market in 2009 and 2010, publishing was purging its own employees, enlarging a parallel community of exiles. Established writers and books on more mainstream topics were still being contracted, of course. But there didn't seem to be great room for new voices or for risk—for first-time authors, like me, wanting to take on "difficult" subjects. I'm not saying that my proposal was perfect or that all rejections were as kind or gently written as the ones I've quoted. I'm saying it cuts to hear that the story of your people is not "big," even when worthy and well written—and it disappoints to hear that "big" seems to mean mainstream and marketable, even to publishers whose mission statements declared otherwise.

This is about when Adorno's words struck such a chord. I had put everything into the pursuit of a story that no one seemed to want. To top it off, the United Kingdom border control office denied me a one-year business visa because, it said, book research didn't constitute a valid business purpose. The officer in Edinburgh who detained me when I tried to enter on a tourist visa instead told me frankly that the meager state of my bank account probably accounted for the rejection. "Plenty of people come here to hole up in nice houses on the Isle of Skye and write," she said.

By then my Nieman stash was gone. I hadn't put it into health insurance. I hadn't put it into the bric-a-brac of a middle-class life: evenings out, eating out. I didn't even put it into an apartment or a house. Everything I had went into research for the book, mostly at archives in the United Kingdom and the West Indies. I had no lease, no mortgage, no permanent address. I lodged or, once or twice, lucked out with a housesitting arrangement. I rented rooms cheaply from friends, friends of friends, mothers of friends, and strangers who looked kindly on starving artists, and acquaintances who believed in what I was trying to do. In my year and a half there, I lived in eight different flats in London.

When I wasn't working on the book, I was working on freelance book reviews or magazine articles or pitches for them or fellowship applications or teaching Saturday morning English classes to 13-year-olds who didn't want to be there, all to replenish the bank account that the border control lady had found so distressing. At one point, my mother, a woman who is anything but acid, told me: "Get a job, and get a life." She said this out of love and concern because all I ever did—all I ever do—is work, seven days a week, practically every waking hour. And who can blame her for thinking that a woman in her mid-30's should not be living with her parents? Who can blame her for thinking her amply and expensively educated daughter should maybe have a place of her own? Or that she should have the time to do things other than work (like, ahem, get married and procreate something other than a book)?

I'm not sharing the sordid details to make you feel pity. Don't. I chose this life. It is exactly what I want to do, and on most days I am thrilled to be doing it. I feel blessed. I have supportive friends and family and colleagues. I have co-publishers I respect and trust: University of Chicago Press and Hurst, an independent press based in London. And somehow I still have enough money to pay for five more months of rent at a writer's studio in Manhattan and subway and train fare to get there.

I'm writing this so you know this is the hardest thing I have ever tried to do. It takes soul-risking hustle and soul-exposing humility, a combination that comes from being rejected repeatedly yet somehow still believing that the ultimate goal is bigger than you or your bruised ego. It takes passion—a downright obsessive love for your subject and belief in its value. And it takes being blessed. It's not something to undertake just because you think books might be a better bet than newspapers right now.

When I was on staff in a newsroom, I was a workaholic. What I did was who I was. And so I made the mistake of identifying my job with a home country. It wasn't. It's still true to say that what I do is who I am. But now I know that this transcends any particular employer, as compelling as health insurance and a biweekly paycheck can sometimes seem. Writing is not a job. It's a vocation, a calling. If you're lucky, it can be a house, too—the thing that shelters you in seasons of transition and constant address changes. It's not the kind of house that Google Earth can locate, but I know exactly where to find it. I make words there every day, words that I believe in, words that I hope will make a contribution, words that have a reality well beyond the imaginary homeland of a newsroom.

Gaiutra Bahadur, a 2008 Nieman Fellow, is writing her first book, "Coolie Woman," which is scheduled to be published in 2012. An excerpt appeared in the Spring 2011 issue of The Virginia Quarterly Review and was reprinted in the Indian magazine The Caravan.