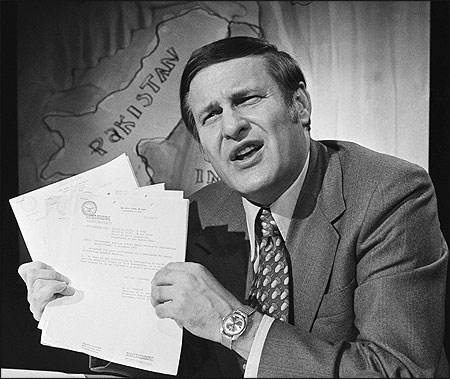

Jack Anderson holds documents, which he says describe White House strategy sessions on the India-Pakistan war, on his television show in 1972. Photo by The Associated Press.

Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington’s Scandal Culture

Mark Feldstein

Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

480 Pages.Every writer who cares about language usage knows that the word "unique" means one of a kind. There are no degrees of uniqueness so caring writers cringe when reading, for example, that an investigative journalist is the "most unique" ever practicing the craft. But if I were to misuse the word, I would do so on behalf of Jack Anderson, an astoundingly unique investigative journalist who died in 2005 at the age of 83. Or should I say "muckraker"? Or is there another descriptive word not yet coined?

These ruminations are occasioned by the publication of "Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture," written by Mark Feldstein. Interesting, informative and important—an all-too-rare combination—Feldstein has written a book that speaks to journalism's past and its present. It is not a full-scale Anderson biography, nor one of Nixon. Instead, as Feldstein explains, it "is an account of the interaction between these two men that illustrates larger issues about government and the media—and the rise of investigative scandal coverage—during their time."

Now a journalism professor at the University of Maryland, Feldstein reported for ABC News and CNN, and before doing that he served as Anderson's intern during the summers of 1973 and 1976. While in that Washington, D.C. office, Feldstein recalls in his book that he "absorbed the spirit of joyful muckraking that permeated" the enterprise. Ever the journalist in his approach to the telling of this intriguing story, Feldstein acknowledges his hope that "this familiarity has not compromised my fairness, but that ultimately will be up to the reader to decide."

Feldstein's research is deep and broad, leading to an excellent book about the numerous and challenging intersections of politics and the press, especially as they exist—and are played out—in Washington. Much of the insight is revealed from what Anderson left behind: more than 10,000 syndicated columns, many of them based on persistent, some might say, compulsive reporting; thousands more magazine and newspaper articles and radio broadcasts; 20 books; speeches; interviews; internal memos mixed in with personal and professional correspondence. What he didn't glean from documents, Feldstein unearthed in the course of his roughly 200 interviews.

For readers too young or otherwise too removed from the decades-long, poisoned relationship of Anderson, the syndicated columnist, and Nixon, the politician and President, I offer a few of its building blocks: Anderson learned some of his trade from mentor Drew Pearson, also a widely published muckraker based in Washington. Pearson and later Anderson went after anybody in authority who offended their personal and political morality, and Nixon showed up frequently—as a Communist-baiting congressman from California, as an ethically challenged vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower, as a failed White House candidate, and later as a twice-elected President. Nixon tended to despise journalists and exhibit paranoia, with Anderson a regular target of his invective; Anderson was a well-recognized enemy of Nixon's long before his administration's top 20 "enemies list" surfaced in 1973—and Anderson's name wasn't on it.

Nixon liked to reside in the international realm and certainly deserves credit for establishing U.S. government relations with China. Though never a foreign correspondent, Anderson relished international scoops, and he is probably best recalled today for exposing Nixon administration lies about who was doing what to whom during warfare between India and Pakistan. Nor did the Vietnam War escape Anderson's relentless effort to bring to public attention the reality of the military campaign as set against the ways in which Nixon (and others in his administration) portrayed its policy.

Journalist's Inner Fire

RELATED ARTICLE

“Steve Weinberg: Connections and Disclosures”

- Steve WeinbergWhat became clear in my own research about Anderson—and is conveyed well by Feldstein—is the vital nature of a journalist's inner fire. Some of the more talented journalists in terms of documents research, interviewing techniques, and writing skills make little impact because they lack the inner fire of Anderson. To those who ask me about investigative reporting—and who are eager to discover why one reporter succeeds at it while another fails—I often use such phrases as "sustained controlled outrage" and "relentless curiosity" to describe this inner fire. Yet words fall short as they fail to capture the alchemy that integrates necessary temperamental qualities into the steady grind of a reporting life.

Among those journalists whose blend of temperament, timing and tenaciousness has propelled them into the ranks of successful muckrakers, besides Anderson, I'd put Ida Tarbell, Seymour Hersh, Jessica Mitford, Ida Wells-Barnett, and the team of Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele, among others. On a local level, with fame more circumscribed, I'd include Mike McGraw, Pam Zekman, Bill Marimow, Bob Greene, Jeff Leen, and at least several dozen others.

The inner fire might be partly genetic—that's hard to know for sure—and deeply environmental. Anderson's environment was connected to his lifelong piety to the Mormon faith. As Feldstein mentions, Anderson "sincerely believed that his muckraking furthered the Lord's work." Not so incidentally, the Mormons believe that God inspired the U.S. Constitution, a document Anderson cited often.

Although I would never compare myself favorably with Anderson, my inner fire springs neither from organized religion (I call myself an evangelical agnostic) nor my parents, in any way I can discern. So where does it come from? After 42 years of investigative reporting, I can't say; I only know it exists and probably will until I die.

Anderson inspired me and many other journalists with his dedicated pursuit of information. He would not tolerate secrecy in government or corporate suites if he had a sense that the citizenry was being screwed. As Feldstein illustrates, if Anderson could not obtain information through standard means, he and his cadre of associates would acquire desired details "by eavesdropping, rifling through garbage, and swiping classified documents." In the tactics these two men used in their back-and-forth attacks on each other—as Feldstein shows Nixon retaliating with wiretaps, smears and even a plot to kill Anderson—they found some discomforting common ground.

Our contemporary culture of extreme government and corporate secrecy would not have altered Anderson's tactics or, I surmise, likely doused his inner fire.

Despite some questionable professional conduct, Anderson remained an evidence-based crusader against corruption until he died. Pause for a moment to take in those words—evidence based. Some of today's digital journalists—here I'm talking about bloggers and their techno cousins— exhibit plenty of passion and an abundance of outrage. A few do use the expansiveness of the Web to its best advantage by connecting readers to an open vault of documents presenting a treasure-trove of supporting details. But without the time-honored, shoe-leather investigative work and skillful interviewing, passion and outrage amount to little in the journalism realm. The great lesson of Feldstein's book, even if considered only in the Anderson-Nixon context, is the vital nature and immense value of thorough watchdog reporting.

Accept no substitute.

Steve Weinberg is the author of seven nonfiction books. His most recent, "Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller," was published by W.W. Norton in 2008. He is professor emeritus at the Missouri School of Journalism and a former executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors.