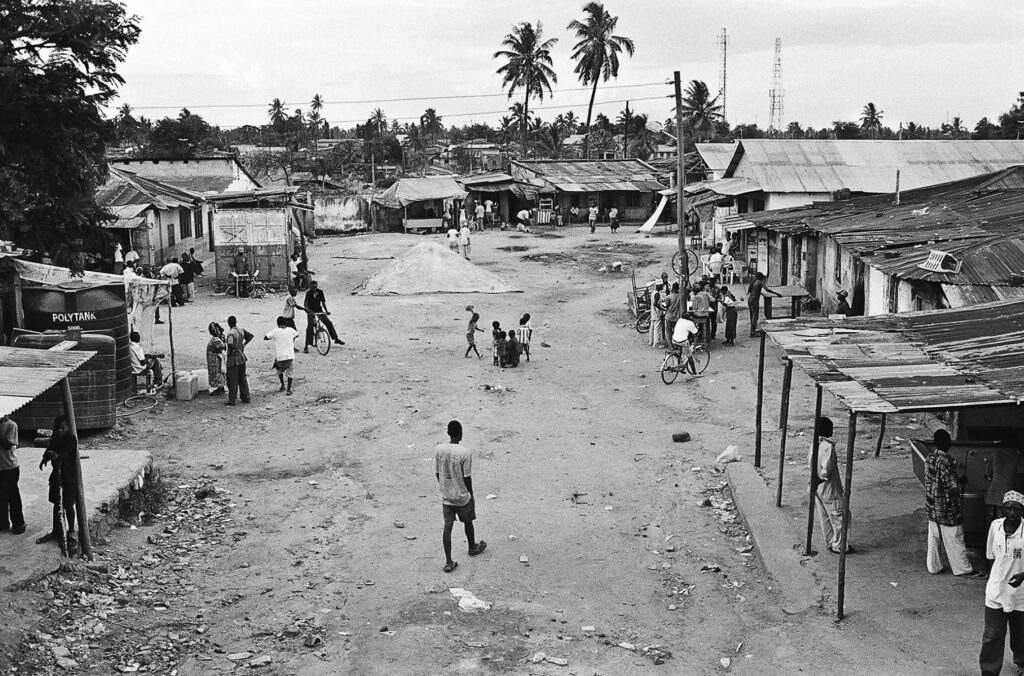

I’m standing at the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro with my close friend and colleague Kevin Sites. At this celebratory moment, watching the sunrise from the “rooftop of Africa,” I have no clue that in a week I will meet the woman I will eventually marry—Jacqueline, a native Tanzanian bank teller from Dar es Salaam. Nor do I know that during a yearlong courtship, which will include three subsequent trips to Tanzania, the foundation of our relationship will be laid in one of the most unloving places on earth, Hyena Square, Dar es Salaam’s notorious bastion of commercial sex workers.

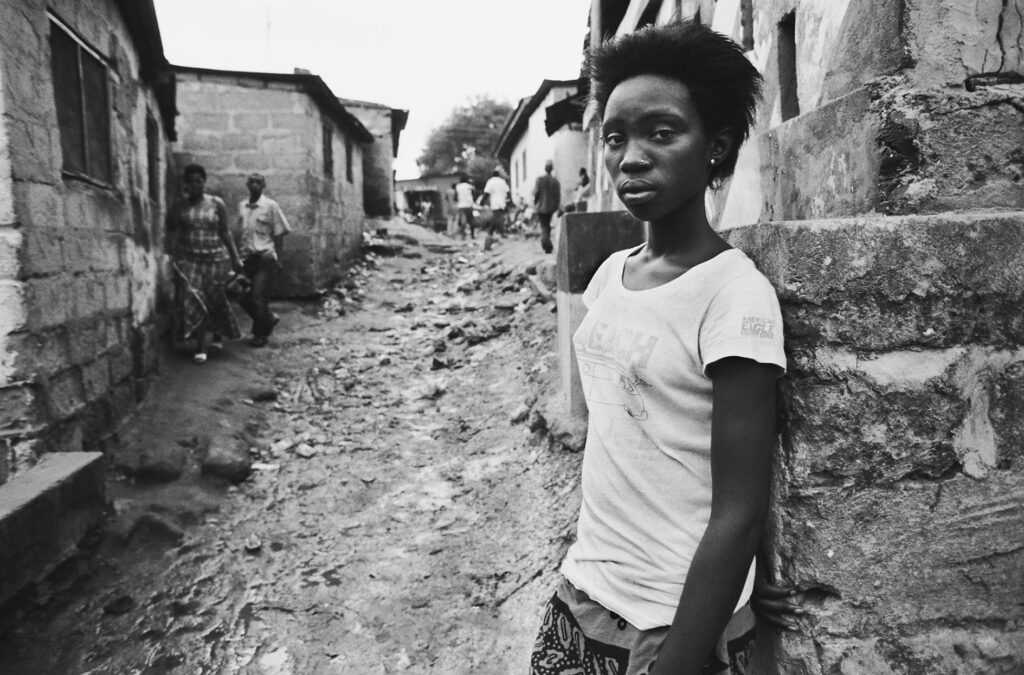

Four months later, Jacqueline and I can barely see the dusty footpath ahead of us, just silhouettes of men against kerosene-lit fried fish stands. I get nervous when she slips the engagement ring I gave her into her pocket for safekeeping. As we enter Hyena Square for the first time, its inhabitants are as surprised by the sight of a Westerner as we are by the droves of emaciated young women selling their bodies for as little as a dollar in the nearly pitch-black night. At least half the girls appear to be infected with HIV/AIDS, but it’s impossible to be sure as they’re all severely malnourished, and many are tejas (Swahili slang for “junkies”). They’ve migrated from dirt-poor villages in search of a better life, but this is what they find.

More

More of Porter’s photos from Hyena Square are available on his Web site.

Jacqueline tells me that there are many open-air flesh markets throughout the city, thousands more teenage sex workers, and little sustained effort by the Tanzanian government to create incentives for girls to remain in their villages or provide alternatives to commercial sex work for those who do come to Dar es Salaam.

At this moment, as a photojournalist, I know that I must try to bring attention to the social injustice I see in front of me. I can only hope that in doing so I will spur humanitarian organizations to lean on the Tanzanian government to reverse this abomination. Jacqueline came from a destitute village in rural Tanzania and feels a connection to these girls. She agrees to be my translator.

We underestimate the challenge all of this poses.

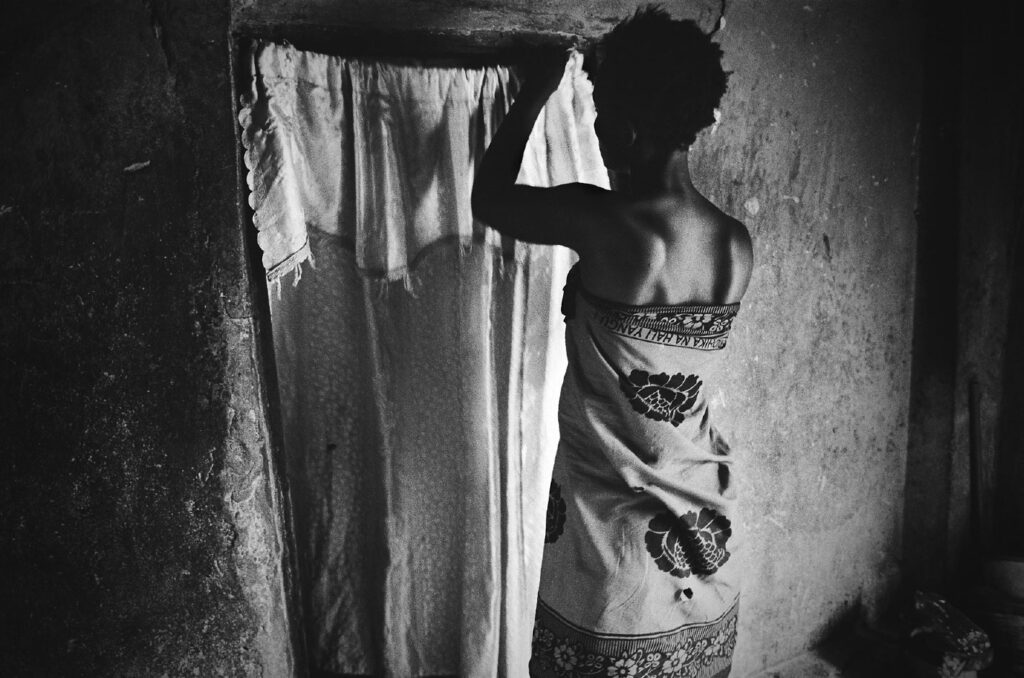

“I’m in the business of selling my kuma (vagina) not my face,” Pili, a 28-year-old prostitute, shouts when she sees my camera. “And if this mzungu (white person) wants my kuma he can come to my room and pay for it like everybody else.”

Within moments we’re surrounded by a mob of prostitutes and johns, pushing, shouting and grabbing at my camera. We’re marched to a cinderblock police outpost where we assure officers that we only photograph those who give us permission. But no one who is present believes we’re here for any reason other than exploitation. To avoid a stint in the outpost’s crowded jail cell, we pay Pili a cash settlement and are released.

It is a shakedown to be sure, one of dozens we will endure in the coming weeks. But Pili’s objections aren’t entirely motivated by cash. Being a prostitute in Tanzania is considered disgraceful and embarrassing, and public knowledge of the fact can bring shame to an entire family.

Despite our promise that the story is strictly meant for Western audiences, the girls are cynical beyond their years. They’re convinced we’ll sell the story to Tanzanian newspapers and TV, revealing their dirty little secret. They may be village girls but they understand the power of the media.

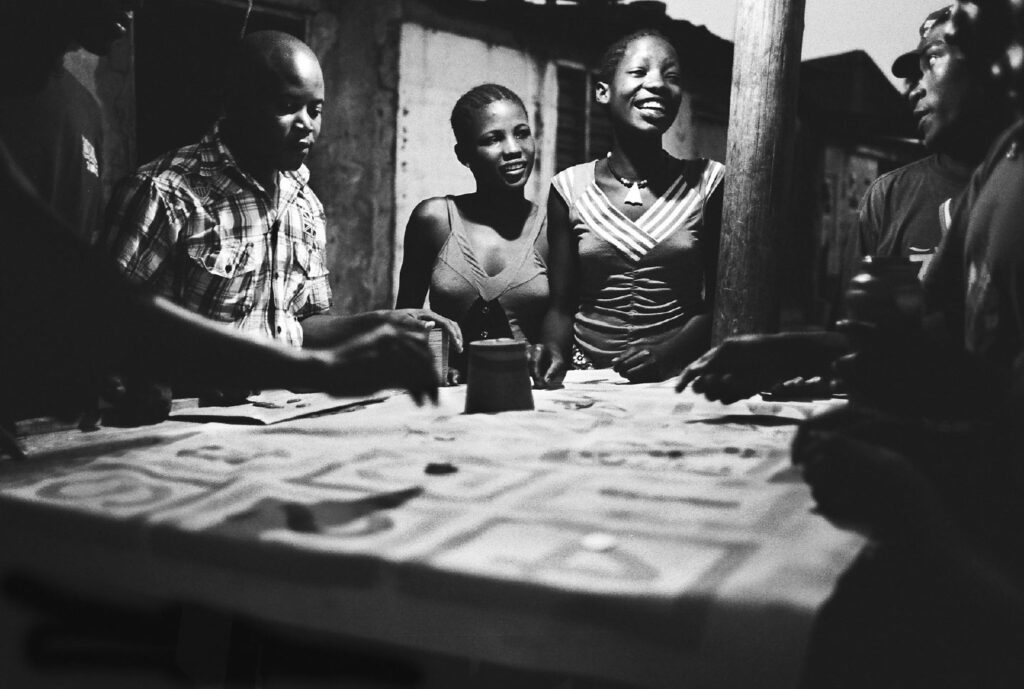

The girls who let us photograph them are subject to the same hostility we are—not just from other prostitutes, but local brew makers, drug dealers, and others who depend on prostitution for their livelihoods. Every time my camera is out of its bag for longer than 60 seconds I find myself retreating to the side of my 5-foot-3-inch fiancée while she goes head-to-head with disgruntled inhabitants. Despite the insults they hurl, she treats them with respect, remembering what it feels like to be pushed to the edge of survival.

I’m humbled by her devotion to me—and to the project. Some of the girls, I can see, are starting to notice this too and slowly begin to trust us.

Ironically, Pili is one of the first to come around. She invites us to take photos and wait in her room—for a small fee, of course. Still, her offers are genuine, and she becomes one of our strongest allies. She tells us that as a teenager she dreamed of becoming Miss Tanzania, but a one-way bus ticket to Dar es Salaam sealed her fate. Now three fatherless children and a drug habit trap her here.

Lili, a newcomer not yet ravaged by the pitfalls of prostitution, becomes like a sister to us. At 16 years old, she’s the youngest prostitute in the area and one of the busiest; men aggressively pursue the younger girls believing they’re less likely to be infected with HIV. Some men force her to have sex without using a condom—others she allows if they offer her more money. Her teenage invincibility prevents her from seeing her destiny, etched on the drawn faces of the other girls.

Her love for the camera is refreshing, but, like Lili, we are blinded by our own ambition. While photographing her outside her “guesthouse” a strung out drug dealer begins hurling baseball-size stones at the three of us. Luckily they whiz past us, denting the corrugated metal siding of the guesthouse instead of our heads. He reveals a stick of chiseled hardwood, promising to beat us with it if he sees us again. A crowd forms behind him echoing his threats.

We’ve finally worn out our welcome—and, sadly, Lili’s too.

On our sofa, Lili looks like a typical teenager in the new clothes we bought her. She watches Swahili hip-hop videos while we make dozens of phone calls, trying to find someone who can take her. Though she can barely spell her name, she knows too well that there aren’t many social safety nets in Tanzania. The next day she disappears with her new wardrobe. We never see Lili again.

For a moment we think about shelving the project. The girls have been victimized enough without us making their struggle for survival even more difficult. I know the inhabitants of Hyena Square fear publicity but after looking at some of the photographs I start to feel differently. While a truthful representation of their situation, the photographs are explicit and difficult to reconcile. It might be that the people to whom I will pitch this story will balk at publishing these pictures and tell me that they are too depressing for audiences to absorb. But the girls have taken risks by allowing us into their lives so we feel a tremendous responsibility to honor their lives by telling the stories they’ve shared with us.

After a much needed break from Hyena Square, we complete the project. Walking along the familiar footpath for the first time in two months, I can feel my heartbeat racing with trepidation but also with excitement. Jacqueline and I are bringing prints to the girls we’ve photographed, and we’re looking forward to their reactions.

Surprisingly, we’re greeted like old friends. The girls giggle and pass the photographs around so everyone can see them. We even bring photos for Lili hoping someone might know her whereabouts, but most can barely remember her. Two new arrivals from Mwanza have taken her place: Neema, 17, and Susie, 16. Neema seems to manage the men who prowl around her. Susie is a deer in the headlights.

Related Article

“This Is How I Go”

– Kevin Sites

The atmosphere is different this time, and for the next few days we are able to photograph with little resistance. On our last night at Hyena Square, Jacqueline and I are swarmed by a group of prostitutes and johns, only this time they are not calling for our arrest—they had come to say goodbye. The photography is finished but my pursuit to expose the betrayal these young women are experiencing is only just beginning.

Jeffrey Porter now combines his career as a feature and documentary filmmaker with being a photojournalist. In one of his films, “A World of Conflict,” he chronicled Kevin Sites’s Yahoo! News Hot Zone project.