A journalist given a new beat or assigned a new topic is expected to be an instant expert, an authority on a subject that’s somewhat unfamiliar. A good journalist, therefore, must be a quick study. “It doesn’t matter how long you’ve known it,” I’ve heard some of my colleagues say. “What matters is that you know it.”

When the subject is New Orleans, however, the honest journalist will admit that instant expertise is impossible to attain. It is a place that often seems impossible to figure out if only because of its many contradictions. For example, New Orleans is a city heavily influenced by France and West Africa and Spain and Haiti and, to some extent, even America, and yet maintains an attitude that it doesn’t want to be influenced by outsiders. New Orleans takes some getting used to.

It is a place where the people sing, even when all they’re doing is talking. It is a place where “Baby” is not only what the waitress calls you when she’s topping off your coffee, but is also how one grown man might refer to another without the suspicion that either one is gay. It is home to accents that are never conveyed accurately in the movies and to grammatical constructions and mispronunciations that confound the newcomer until he considers that English was not the city’s first language. Nor was it the second.

Knowing those things can help a columnist writing for the daily newspaper, but embracing those quirks helps even more. That is, it is not enough to know New Orleans’s peculiar history; that can be found in books. It is more important to acknowledge that the differences represent a perfectly acceptable way of being and to remember that because the city doesn’t want to be like any place else, comparing it to every place else is a surefire way to both insult its residents and overlook its unique charm.

Accepting the city for what it is does not mean accepting things the way they are. If everything were perfect, there would be no columnists. No, it means accepting New Orleans’s idiosyncrasies, its multiple personalities, as the positives they are while blasting away at those things that threaten the city’s way of life, if not its very existence.

Who’d have thought that we’d ever be talking about threats to the city’s existence? Or that there would ever be a debate as to whether this city — this city of all cities — should continue to exist? The Times-Picayune can’t have but one forceful opinion on that topic, and I’ve been fortunate enough to be one of the ones who gets to express it.

Defending New Orleans

I wrote a weekly column for the newspaper before catastrophic levee failures put 80 percent of New Orleans under water, but those columns now appear to me to have been written by a different person. There’s a difference between writing from a city where everybody wants to come at least once to party and writing from a city that some government officials say no longer deserves to be. Before the storm, I was an editorial writer who had fun writing a weekly column. Thanks to an executive decision by editor Jim Amoss and editorial page editor Terri Troncale, but more significantly to the transformative power of anger, I was converted into a full-time columnist who took on the serious work of defending a city.

I was not born in New Orleans and, given the city’s aforementioned resistance to outsiders’ opinions, that is probably reason enough for some New Orleanians to ignore what I have to say. Just the other day I heard a local pundit exclaim, “You don’t choose to be a New Orleanian. You’re born a New Orleanian.” He was serious. By his definition, I will never, can never, be of this city.

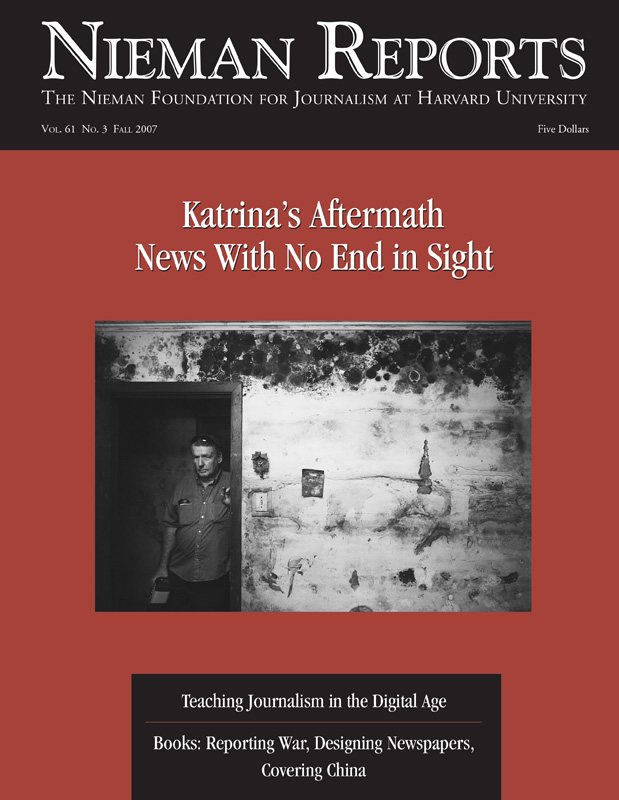

But I am not a mercenary. This fight for the city’s survival is as personal for me as it is for the native born. I know what it’s like to lose a house, a car, and one’s entire community in one fell swoop. I know what it’s like to see one’s personal belongings in a sodden heap on a buckled-up hardwood floor. I know what it’s like to say I have something — a book, a CD, an article of clothing, a photograph — and in the middle of that sentence stop myself and say, “Well, I used to have ….”

I think of myself as an advocate for those who used to have. Granted, not all those who used to have will always think of me as an advocate for them. Though everybody here is in agreement that New Orleans should continue to be, there is no consensus as to how it should be. I am in favor of a denser city, where most people live on the city’s natural ridges and fewer people live in the areas that were populated after the swamps were pumped dry. However, many people who live in those neighborhoods respond that the Army Corps of Engineers promised them protection, too, and that they have as much right to go home as anybody else. Besides, insurance settlements must be spent on the damaged property. Where else can they go?

In the larger sense, it doesn’t matter if my readers and I disagree about some of the issues related to rebuilding. What matters is that my opinions are built on a foundation of love and respect for the city and its culture and that I not pretend to be objective when those readers are desperate for someone who will passionately defend them.

Though I am personally in as much trouble and dealing with as much worry as the people I interview, I cannot imagine a more enviable assignment. Hurricane Katrina, with the exception of the terrorist attacks of 2001, is the most significant American news story of this young century. Some may have originally categorized it as a weather story, but it’s much more wide reaching than that. Can an American city really die before our eyes? What are the consequences of long-term poverty, as epitomized by what happened here? Is homeownership really the safest way to build wealth? What happens when the people in a relatively isolated city become a diaspora? How does the federal government respond when it is to blame for much of the ineptitude we’ve experienced? Who have we become — both as a forgetful and dismissive nation and as a city trying to reform itself?

The opportunity to write about these things has come at a great cost. To be the observer and commentator, I’ve had to live in a struggling city where I am also the thing observed. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. New Orleans is my home. I long ago stopped trying to figure it out, even stopped trying to figure out why I live here. The simple answer is that it’s the experience for me. And it’s the experience that hundreds of thousands of those making up the diaspora long to know again.

Jarvis DeBerry is a columnist at The Times-Picayune.

When the subject is New Orleans, however, the honest journalist will admit that instant expertise is impossible to attain. It is a place that often seems impossible to figure out if only because of its many contradictions. For example, New Orleans is a city heavily influenced by France and West Africa and Spain and Haiti and, to some extent, even America, and yet maintains an attitude that it doesn’t want to be influenced by outsiders. New Orleans takes some getting used to.

It is a place where the people sing, even when all they’re doing is talking. It is a place where “Baby” is not only what the waitress calls you when she’s topping off your coffee, but is also how one grown man might refer to another without the suspicion that either one is gay. It is home to accents that are never conveyed accurately in the movies and to grammatical constructions and mispronunciations that confound the newcomer until he considers that English was not the city’s first language. Nor was it the second.

Knowing those things can help a columnist writing for the daily newspaper, but embracing those quirks helps even more. That is, it is not enough to know New Orleans’s peculiar history; that can be found in books. It is more important to acknowledge that the differences represent a perfectly acceptable way of being and to remember that because the city doesn’t want to be like any place else, comparing it to every place else is a surefire way to both insult its residents and overlook its unique charm.

Accepting the city for what it is does not mean accepting things the way they are. If everything were perfect, there would be no columnists. No, it means accepting New Orleans’s idiosyncrasies, its multiple personalities, as the positives they are while blasting away at those things that threaten the city’s way of life, if not its very existence.

Who’d have thought that we’d ever be talking about threats to the city’s existence? Or that there would ever be a debate as to whether this city — this city of all cities — should continue to exist? The Times-Picayune can’t have but one forceful opinion on that topic, and I’ve been fortunate enough to be one of the ones who gets to express it.

Defending New Orleans

I wrote a weekly column for the newspaper before catastrophic levee failures put 80 percent of New Orleans under water, but those columns now appear to me to have been written by a different person. There’s a difference between writing from a city where everybody wants to come at least once to party and writing from a city that some government officials say no longer deserves to be. Before the storm, I was an editorial writer who had fun writing a weekly column. Thanks to an executive decision by editor Jim Amoss and editorial page editor Terri Troncale, but more significantly to the transformative power of anger, I was converted into a full-time columnist who took on the serious work of defending a city.

I was not born in New Orleans and, given the city’s aforementioned resistance to outsiders’ opinions, that is probably reason enough for some New Orleanians to ignore what I have to say. Just the other day I heard a local pundit exclaim, “You don’t choose to be a New Orleanian. You’re born a New Orleanian.” He was serious. By his definition, I will never, can never, be of this city.

But I am not a mercenary. This fight for the city’s survival is as personal for me as it is for the native born. I know what it’s like to lose a house, a car, and one’s entire community in one fell swoop. I know what it’s like to see one’s personal belongings in a sodden heap on a buckled-up hardwood floor. I know what it’s like to say I have something — a book, a CD, an article of clothing, a photograph — and in the middle of that sentence stop myself and say, “Well, I used to have ….”

I think of myself as an advocate for those who used to have. Granted, not all those who used to have will always think of me as an advocate for them. Though everybody here is in agreement that New Orleans should continue to be, there is no consensus as to how it should be. I am in favor of a denser city, where most people live on the city’s natural ridges and fewer people live in the areas that were populated after the swamps were pumped dry. However, many people who live in those neighborhoods respond that the Army Corps of Engineers promised them protection, too, and that they have as much right to go home as anybody else. Besides, insurance settlements must be spent on the damaged property. Where else can they go?

In the larger sense, it doesn’t matter if my readers and I disagree about some of the issues related to rebuilding. What matters is that my opinions are built on a foundation of love and respect for the city and its culture and that I not pretend to be objective when those readers are desperate for someone who will passionately defend them.

Though I am personally in as much trouble and dealing with as much worry as the people I interview, I cannot imagine a more enviable assignment. Hurricane Katrina, with the exception of the terrorist attacks of 2001, is the most significant American news story of this young century. Some may have originally categorized it as a weather story, but it’s much more wide reaching than that. Can an American city really die before our eyes? What are the consequences of long-term poverty, as epitomized by what happened here? Is homeownership really the safest way to build wealth? What happens when the people in a relatively isolated city become a diaspora? How does the federal government respond when it is to blame for much of the ineptitude we’ve experienced? Who have we become — both as a forgetful and dismissive nation and as a city trying to reform itself?

The opportunity to write about these things has come at a great cost. To be the observer and commentator, I’ve had to live in a struggling city where I am also the thing observed. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. New Orleans is my home. I long ago stopped trying to figure it out, even stopped trying to figure out why I live here. The simple answer is that it’s the experience for me. And it’s the experience that hundreds of thousands of those making up the diaspora long to know again.

Jarvis DeBerry is a columnist at The Times-Picayune.