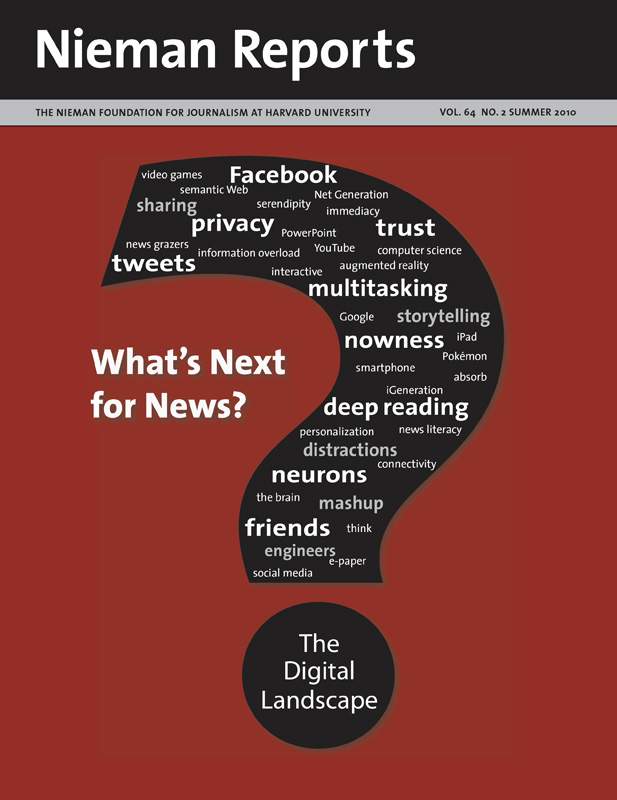

Pokémon has become much more than a video game. It taught a generation of kids that they are more than consumers: They are participants, experts and creators of media. Photo by Shea Walsh/AP Images for Pokémon.

A year and a half ago, my research team released the findings from a three-year study of how young people use new media in social and recreational settings. In summarizing findings from the Digital Youth Project, we wanted to focus press attention on the learning opportunities we had found being supported by interactive and online media. When I spoke with journalists about our research, I emphasized the need for adults to support the positive potential of informal and social learning online rather than assume that the time that kids spend with digital media is always a distraction or waste of time.

More often than not, however, teachers asked me about strategies to disengage kids from social media so they can focus on their studies. And journalists seemed most interested in how online networks escalate peer pressure and bullying. Whether it is teachers trying to manage texting in the classroom, parents attempting to set limits on screen time, or journalists painting pictures of a generation of networked kids who lack any attention span, adults seem to want to hold on to to their negative views of teen’s engagement with social media.

This generational gap in how people regard social media means that kids and adults are often in conflict about what participation in public life means. Not surprisingly, cultural and educational organizations also seem out of step with how young people learn and access information. It is critical to acknowledge the radically different media environment kids inhabit today while also appreciating both the positive and negative aspects of these changes. Now young people can be connected 24/7 to peers, information and entertainment, and their attention is captured through visual media, participation and interaction.

All of these differences challenge journalists as they redesign their models of communicating news and information. In today’s media environment, daily life is far more porous in accepting a diverse range of information and social interactions, and this circumstance can complicate and enhance the task of reaching and engaging youths. In fact, this isn’t just about youths, though they are emblematic of these changes. All of us are living through a profound shift in how we engage with culture, knowledge, information, news, events, society and our social lives.

To create a digital public sphere that both engages and informs requires that we find ways of bridging the gap in our understanding of the networked world. Yet if we can capitalize on the potential of social media, we’ll discover unprecedented opportunity in highly personalized and participatory public engagement.

Our study, the Digital Youth Project, was part of a larger effort by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s digital media and learning initiative to understand how young people’s lives are changing as a result of digital media. Our research involved hundreds of youths across the United States and relied on the efforts of 28 researchers and collaborators. While we did not examine their media practices with the journalism and news media industry in mind, our key findings can be of significant value to journalistic organizations that are figuring out how to bring news and information to the next generation.

Ours is in many ways a hopeful story. Our research leads us to believe that organizations and institutions that serve youth can still have their best days ahead of them if they engage with youths’ peer cultures and social communication. Creating interest-driven content and programming that is easily shared, interactive and participatory is key to unlocking the power of networked media.

Learning From Pokémon

Before we explore what’s taking shape today, let’s look back to the late 1990’s when Pokémon swept through childhood culture. Those who are graduating from college now are the first post-Pokémon generation. These are kids who grew up with ubiquitous social gaming and convergent media as a central part of their peer culture.

Pokémon incorporated video games, trading cards, a television series, movies and a wide range of merchandise. It also broke new ground by placing gaming and social action at the center of the transmedia equation. Its content invites collection, strategizing and trading activity, and as such it is a form of media that is not an end in itself. Instead, it mobilizes youth to do something with it.

What is different about contemporary social media such as Pokémon is that personalization and remix is a precondition of participation. At its core, it is about engagement and communication. And this is what social media means for this generation—not just media that are about social communication but also media that invite social exchange. Marketers talk about this as viral or contagious media. For kids, it means media that have social currency. They are consumers, but more importantly they are participants, experts and creators.

There is much we can learn about kids’ learning and engagement with Pokémon. What follows are a few of the lessons that relate directly to the tasks of journalism:

- Skills and literacy are a byproduct of social engagement. Kids are not playing Pokémon with the explicit goal of learning skills or gaining knowledge. We’re starting to see some research coming out about the kinds of complex language skills and visual literacy that kids pick up with complex gaming environments like Pokémon or Yu-Gi-oh. But again it is a byproduct, not a focus of the engagement.

- The focus is on demand, not supply. In their new book, “The Power of Pull,” John Hagel, John Seely Brown, and Lang Davison write about a cultural shift from supply-push to demand-pull. Instead of working to build stable stocks of information in kids’ heads—in supplying a standardized body of knowledge—demand-pull is about giving kids skills and dispositions to be able to access and draw from a highly dynamic and unstable information environment that is too massive for them to internalize.

- Sources of expertise come from peers, not institutionalized authorities. Kids occasionally consult rule books, but they will far more often look to their peers for knowledge. Certain kids in a given peer culture will gain reputations as Pokémon experts, and the more advanced of these will be posting walk-throughs, reviews and cheats on Web sites that a much broader range of kids will be accessing. It’s about peers assessing and providing feedback rather than relying on institutional gatekeepers. The excitement comes from taking on the roles of participants, experts and knowledge creators, not simply knowledge consumers.

- Networked games support specialization, the development of personalized relationships to the content, and subject matter expertise. Instead of being asked to master a standardized body of knowledge that is the same for all their peers, measured against prescribed benchmarks, these more informal digital environments allow kids to choose their own areas of interest and engagement. One kid can develop a reputation as a water Pokémon trainer and expert; another can master the universe of cheat codes.

- The overall knowledge ecology is highly distributed. The circulation of information and knowledge and the learning is distributed across different kids, different sites, and different media platforms.

What Lies Ahead?

As kids grow older, they bring experiences from media like Pokémon to their participation in the teen social scene. Just as with childhood play, teenage peer sociability takes place in networked and digital environments. Negotiations over status and popularity that once happened in school lunchrooms and hallways now migrate to MySpace, Facebook and text messaging. For the post-Pokémon generation, these online community spaces are seamless with the offline settings of their daily lives.

Although peer spaces involving teen friendship are quite different from those that center on interests like Pokémon, peer culture operates in similar ways in both. And what happens in these social media spaces differs from what takes place in spaces presented to them by most adults. With mainstream media, as with other content and activities adults offer, teens find themselves acting primarily as consumers of information. In their media environments they are producers and distributors of content, knowledge, taste and culture; they make decisions about how to craft their profiles, what messages to write, and the kind of music, video and artwork they want to post, link to, and share. These choices about what media to display and circulate are made in a public (nonprivate) space and have consequences for their reputation in the social circles that matter to them the most.

Where are things headed? It’s good to remember that these are still early days of social media and our experimentation with harnessing digital media in the service of communication, engagement and knowledge acquisition. And many of us still carry the weight of assumptions, practices and institutions that no longer fit well with the emerging digital environment.

Historically we also have separated our kids’ peer cultures from their learning and engagement; this has created antagonism between education and entertainment media and demarcated boundaries separating adult-mediated institutions from youth-produced ones. These are major encumbrances as we move forward. Yet for those willing to experiment and seize the opportunities that today’s always-on, fully networked technology offers, tremendous opportunity exists to expand our reach to a new generation.

Mizuko Ito is a cultural anthropologist who specializes in digital media and youth culture. She is research director for the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub, a MacArthur Foundation-funded effort at the University of California Humanities Research Institute that is analyzing the impact of the Internet and digital media’s evolving relationship to education/learning, politics/civics, and youth. More information about initiatives at this research hub can be found at DMLcentral.net.