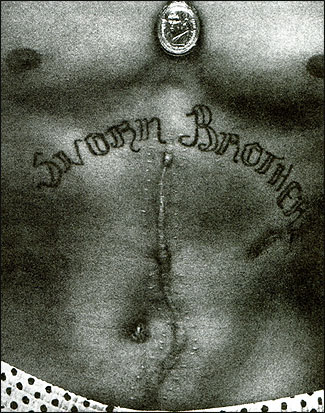

Kitt Philaphandeth, 19, of Lowell, Massachusetts, a member of the Sworn Brotherz gang: “If I was never in it, I’d be the coolest kid…if I leave, I’d get jumped out.” Stan Grossfeld, from “Lost Futures: Our Forgotten Children,” Aperture.

Garrison Keillor had it right. “Every murder,” he said, “turns into 50 episodes. It’s as bloody as Shakespeare but without the intelligence and the poetry. If you watch television news you know less about the world than if you drank gin from a bottle.” Unfortunately, Keillor’s comment increasingly characterizes much of the reporting—both print and electronic—that we find today in the media’s coverage of violence and juvenile crime.

Admittedly, it comes out of a well-established tradition. From Plato to William Golding, the young seem always to be vested with a potential for dissolution and violence. But what accounts for this consistent, historic pattern? Clearly, it is not juvenile crime.

A quarter century ago, the great American sociologist Herbert Blumer noted that the way we define “social problems” has less to do with their seriousness or frequency than with the role political figures and powerful organizations play in fomenting concern about them, while ignoring other issues. Blumer held that it’s therefore as important to plumb the process of how something gets to be viewed as a problem as it is to study the “problem.”

In a rare early application of this idea, Brooklyn College sociologist Mark Fishman described how the New York City media (the three largest daily newspapers and the five major local television stations), created the perception that there was a “crime wave” of juvenile attacks on the elderly in the early 1970’s. At the time, no objective evidence backed up the premise of this reporting.

Fishman discovered that journalists and reporters had set “a crime wave dynamic” in motion as they noticed one another reporting on the same theme of “crimes against the elderly.” Those news organizations that began “wave” reporting found support as other news outlets joined in thereby confirming the judgment that “this thing really is a type of crime happening now.” Indeed, isolated incidents fed the crime wave theme as the press followed a juvenile from arrest, to interrogation, arraignment, trial, sentencing, and finally incarceration. This was paired with periodic interviews of victims, “potential” victims, and interested others. Usually this meant people involved in law enforcement.

Each variation on the theme justified another. Soon the average viewer had the impression that there was a growing “juvenile crime wave.” In the wake of this reporting, bills were introduced into the New York state legislature mandating long prison sentences for youthful offenders and making juvenile records available.

Now, with the proliferation of the Internet, the blurring of entertainment and news, and the availability of Nexis (giving journalists the ability to create national “waves” of juvenile crime with the entry of a search word), the potential for “ride the wave reporting” has increased exponentially. And this time around, as it is happening, the process has resulted in the introduction of some of the most misguided juvenile crime legislation in recent memory.

How has the media covered violent juvenile crime recently? The latest “theme” was prompted by Northeastern University criminologist James Fox in 1995. Noting a rise in arrests of juveniles for violent crimes in the late 1980’s, Fox combined this observation with the expectation of a substantial growth in the teenaged population during the next 15 years. Unless things changed, so the thesis went, an influx of violent and predatory youth would plague the country shortly after the turn of the century. Accompanying his demographic scenario, Fox recommended a set of shifts in national policy to stem the approaching catastrophe, such things as early childhood intervention, better education, alternative programs and employment assistance.

Although Fox’s premise was shaky at best (arrests of juveniles for violent crime began falling shortly after his dire predictions), the suggestion that the nation would shortly be inundated with a new breed of predatory teenager touched a “hot” button in the press. For a while, Fox became something of a fixture on news programs and talk shows and an oft-quoted expert in major newspapers such as The New York Times and USA Today.

Unfortunately, Fox’s thesis was irresistible, too, to policymakers. Barely had the words “three strikes and you’re out!” been applied to the field of criminal justice and put into the media’s feeding chain when a new, powerful sound bite, one which seemed capable of quintessentially defining this new social plague, emerged—the juvenile “superpredator!”

Conservative writer John DiIulio parsed Fox’s thesis by predicting that 270,000 additional “superpredators” would pour into the streets by 2010. He based this conclusion on the premise that six percent of all juveniles would become “superpredators.” With the under-18 population burgeoning from 32 million to 36.5 million by 2010, DiIulio came up with just the number that many in the media were looking for. As University of California criminologist Franklin Zimring commented at the time, DiIulio didn’t address the implication of six percent of all juveniles being superpredators, nor did he help to unravel the mystery of what it meant to already have almost two million of them among us. This, after all, is twice as many kids as are referred annually to all the juvenile courts in the country.

Using DiIulio’s formula, Zimring calculated that even in 2010, among the 270,000 “newly arrived” superpredators, more would be under age six than over the age of 13. “If politicians and analysts can believe in ‘superpredator’ toddlers,” said Zimring, “they can believe in anything.” And indeed, they could, and members of the press were first among the true believers.

“Superpredators Arrive” trumpeted Newsweek in January of 1996, along with the question, “Should we cage the new breed of vicious kids?” Newsweek noted that fear of this new child psychopath had begun to spawn harsh legislative proposals. They cited Arizona’s then law-and-order-governor Fife Symington’s (now in federal prison himself) drive to abolish the juvenile court. “It’s ‘Lord of the Flies’ on a massive scale,” added Cook County State’s Attorney Jack O’Malley.

By March of 1996, the theme of the feral juvenile was in full gear. In a cover article headlined “Teenage Time Bombs,” U.S. News & World Report wrote: “Victims of underage felons [are] challenging the long-standing belief that youngsters who kill, rob and rape should be treated in a different way than adult criminals.” The writers of the article went on to describe an Ohio case involving two boys, ages six and 10, who had killed a two-1/2-year-old girl as further evidence of this new breed of kid killer. As is usually the case, the politicians weren’t far behind.

By June, The New York Times was reporting that Republicans in Congress were moving “to overturn what has been a fundamental principle of the American juvenile justice system for more than 150 years: the strict separation of jailed young offenders from hardened adult criminals.” In his campaign for President, Bob Dole borrowed both DiIulio’s dire predictions and his language—“superpredators”—for use in a national radio address on crime and juvenile justice.

Representative Bill McCollum (R-Florida), Chairman of the House subcommittee, introduced “The Violent Youth Predator Act of 1996.” In a background statement entitled “The Coming Storm of Violent Juvenile Crime,” McCollum described the youth predator as a juvenile who is likely to come from a fatherless home and reflect a “sharp turn for the worse in drug use.” “Brace yourself,” warned McCollum in his statement, “for the coming generation of ‘superpredators.’”

One might think that in stemming an onslaught of the teenaged superpredators in 2010, we might see legislation directed at diverting these who were then two- and three-year-old toddlers from a life of violent crime. No such luck! Indeed, legislative proposals focused instead on fingerprinting juveniles, photographing them, housing them in adult jails, meting out mandatory sentences, “escalating sanctions,” and imposing sanctions on states that shy from prosecuting 13-year-olds in adult courts. Things weren’t much better on the Senate side. Senators Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), powerful Chair of the Judiciary Committee, and Jeff Sessions (R-Alabama) introduced legislation that would jail runaways with adult prisoners and expel kids from school up to six months for smoking cigarettes.

States also took up the gauntlet with vigor. For example, in Texas, legislation was introduced to make 12-year-olds eligible for the death penalty—although they wouldn’t actually be executed until their 17th birthday. Each of these bills all but ignored preventive and treatment programs.

As this term “superpredator” was taking on added political significance, it also assumed not very subtle racial implications—incorporating elements of what Lani Guinier once termed the “rhetorical wink”—whereby code phrases communicate a well-understood but implicit meaning while allowing the speaker to deny any such meaning. The word “superpredators” carried minimal political risk when used in the context of getting “tough” on juvenile crime. Again, this wasn’t particularly new.

In a 1975 cover story on violent juveniles in The New York Times magazine, after describing in gruesome detail the torture and rape of two 10-year-old white youngsters by two African-American youths ages 14 and 15, the author summed up the thesis for that decade. “It’s as though our society had bred a new genetic strain,” he wrote, “the child murderer who feels no remorse.” Though no one explicitly said so, everyone knew to whom the writer referred and in whom this “genetic strain” resided. Conjuring up the specter of a growing breed of feral inner-city children, this article foreshadowed much of the contemporary reporting on violent juveniles, arriving as it so often does with a word that comes packaged with a “wink.”

Probably as much due to the preoccupation in Washington with Monica Lewinsky as anything else, the Senate and House subcommittees never quite got around to reconciling their superpredator crime bills before it was time to adjourn. Senator Hatch blamed liberals in Congress for “failing to protect the public…and [walking] away from negotiations” at the last moment. He vowed to make this juvenile crime bill a top priority in the 106th Congress.

Hatch’s promise is a warning that we can expect another round of putative “waves” of violent juvenile crime in the near future. If the process drags on, it’s possible that the “superpredator” panic will be replaced by another theme as some juvenile somewhere does something that gives rise to another new characterization. Given the current political milieu, it is as likely to arise out of political opportunity as out of any new reality.

Consider the FBI statistics on violent juvenile crime. Arrests of juveniles for “violent crimes” (which measure “crime rates”) seldom reveal the actual behavior. No one is touched in 80 percent of these “violent” crimes. The violent crime can be a threat or perceived threat. Of the 239,700 violent crimes processed by the nation’s juvenile courts between 1985 and 1990, fully 84 percent (202,300) were dismissed, handled informally or “non-adjudicated” as relatively insignificant.

Only slightly more than 900 of the 20,000-plus murders recorded annually in the United States are eventually proven to have been committed by juveniles. Most involve altercations between friends and relatives. One in ten involves a teenager killing a parent or parents—and when that does happen it is usually within the context of an abusive relationship. Each year, fewer than 300 juveniles are convicted of killing a stranger.

Even the apparent rash of tragic school shootings this past year did not foreshadow a new “wave” of such events. School shootings have been on the decline—55 such deaths in the 1992-93 school year vs. 40 during the 1997-98 school year. Moreover, a significant number of “school shootings” involve domestic or personal squabbles among teachers, husbands, maintenance workers and others while on school grounds.

And what about the very young “predators”—those 7-, 10- and 12-year-olds, who are said to be rising Omen-like among us? Unfortunately, homicides by very young children are nothing new. In reviewing 975 homicides that happened 30 years ago in and around that city, Cleveland’s deputy coroner found that five—some of which were unusually brutal—were committed by children age eight or younger. Nationally, the number of children under age 13 arrested for homicide has not changed appreciably for 32 years. More children under age 13 were arrested for murder in 1965 (25) than in 1996 (16).

Where does all this leave reporting on juvenile crime and violence? On some days, I prefer to believe that by understanding more about the traps the media can fall into in covering this topic, the mistakes of the past won’t plague future reporting. But then, I intersect with someone in the media again, and my hope that knowledge might transform the process quickly fades. On various occasions during the hype over “superpredators,” I’ve been interviewed by news personalities as diverse as Diane Sawyer and Bill Moyers. May I say that I’d consider it progress if they’d been able to wipe the look of disappointment from their faces when I declined to join the pack in pursuit of superpredators. By God, they might even air my interviews someday! Not likely. I’d best drink gin from a bottle.

Jerome G. Miller is Co-founder of the National Center of Institutions and Alternatives and Clinical Director of the Augustus Institute in Alexandria, Virginia. His 1990 book, “Last One Over the Wall,” won the Edward Sagarin Prize of the American Society of Criminology. His most recent book is “Search & Destroy: African Americans in the Criminal Justice System.”