Photo by Robert Durell, The Los Angeles Times.

In May 1998, The Los Angeles Times published an exhaustive look at the problem of California’s schools—three special sections, 20 pages in all, entitled “Public Education: California’s Perilous Slide.” The project documented the disastrous effects of two decades of neglect—the worst overall ratio of teachers to students in the nation, 31,000 classrooms statewide presided over by men and women who lack a teaching certificate, and test scores in math and reading that are among the lowest in the nation.

The project, which had been six months in the making, engaged the efforts of more than 20 reporters and photographers. It prompted an enormous reaction among readers and helped galvanize the attention of state leaders. The state’s current efforts at education reform are heavily aimed at the two issues—teacher training and system-wide accountability—that were the focus of the project’s final installment.

Once the exhaustion of getting the project into print wore off, discussions within the paper turned to the question, “now what?”

We had devoted huge resources to calling attention to the problems of education, and clearly our readers cared about the issue. We certainly did not want to abandon the field, but neither could we simply do more of the same without being repetitious.

Times publisher Mark Willes had been greatly impressed by a project launched the previous year at The Baltimore Sun, which is also a Times Mirror paper. The Sun’s Reading by Nine project set a simple, albeit ambitious, goal: engage the community to get every child to read at grade level by the end of the third grade—the year that reading experts have identified as the make or break point for academic success.

To achieve that goal, The Sun had highlighted lagging reading scores in Baltimore, focused on the lack of phonics instruction in the schools, and encouraged employees of the paper and members of the community to tutor students in schools with particularly bad scores.

Willes, greatly concerned about the evidence reinforced in our series that hundreds of thousands of children in southern California read far below grade level, asked if the same effort could be replicated here.

His proposal faced some immediate problems. The most important involved scale. The Sun’s project dealt largely with one school district, Baltimore. By contrast, The Times’s core circulation area covers major portions of five counties. The roughly 800 elementary schools in our region are governed by scores of independent school districts. The Los Angeles Unified School District is by far the biggest—the second-largest in the country. But our circulation area also includes such sizable cities as Long Beach, Santa Ana, Ventura and Riverside as well as suburban districts and tiny rural outposts with only one school.

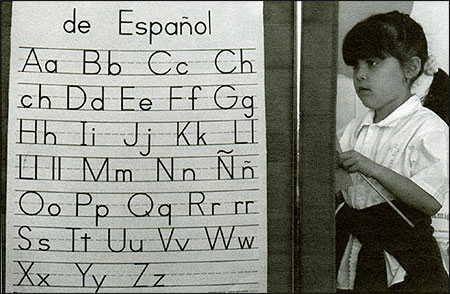

Moreover, the policy issue that The Sun focused on—whole language versus phonics—had already been resolved in California, at least on the policy level. State officials had adopted a new phonics-based curriculum earlier in the decade. In California, other issues such as teacher training, accountability and bilingualism were at the forefront of public concern.

As people in The Times’s community affairs office began to examine the size of the effort that would be needed to launch a Reading by Nine program in so vast a region, it became clear that the organizational task, alone, would take far more time than anyone had initially realized. On the newsroom side of the paper, however, Times Editor Michael Parks had concluded we should not wait.

And so, with the beginning of the new school year in September, The Times launched a second major education project for 1998—a series of page-one stories, one each Sunday from September on into November, that would examine different facets of our reading problem. In the meantime, our colleagues on the corporate side of The Times would continue to lay the groundwork for the work the newspaper would be doing in the community.

That two-track approach proved to have several advantages. Reporters and some editors were concerned, when the effort was first announced, that the compromises and political coalitions that might be necessary for a successful public campaign could affect our journalism. If, for example, The Times on a corporate level were to back a particular reading method as part of the Reading by Nine campaign, would that affect the sorts of stories we wrote? By putting our news coverage on a faster track than the overall corporate campaign, we allayed those concerns.

A second nagging fear remained: Would we be able to find enough newsworthy stories to sustain a continuing series? That fear was put to rest soon after the project was launched. As word spread that the Reading series was a major priority for the fall, reporters from all parts of The Times began to suggest ideas: Washington Bureau reporter Melissa Healy examined preschool reading programs, and education specialist Richard Colvin teamed up with one of our senior Washington reporters, Richard Cooper, to look at school reform efforts nationwide. Another education writer, Duke Helfand, looked at companies that are hoping to make money off the state’s move back into phonics while Elizabeth Mehren, a national correspondent based in Boston, examined the rising phenomenon of merchandise being sold as tie-ins to children’s books.

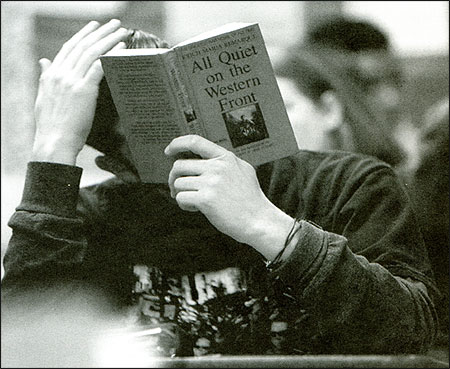

The article that drew the most reader response so far came from Robert Lee Hotz, one of our science writers, who produced a fascinating look at new research into the neurobiology of reading and the insights that the research has begun to supply for teachers.

The stories not only drew attention to the issue of reading, they also illuminated new facets of the broader national debate over improving our schools. And as time went on, we discovered that far from running out of stories, exploration of reading was turning up more ideas as we went along.

In mid-fall, a page-one letter to readers from Willes and Parks announced that The Times was committed to a five-year effort to help our communities teach all children to read by age nine. The paper’s work is two-fold: On the newsroom side, we are committed to explaining, analyzing and clarifying issues, monitoring success or failure of statewide and community efforts, and making sure that public officials know their work is being watched. On the business side, a task force of executives from all departments has been deeply involved in planning a region-wide Reading by Nine campaign. How exactly these two initiatives will work in tandem is not yet clear since the corporate effort is not yet fully engaged.

As our newsroom efforts unfolded, readers across Southern California began to take notice. In addition to letters and E-mail, we started to find that at community forums and speeches to outside groups—regardless of the ostensible topic—someone in the audience almost always brought up Reading by Nine. To extend the effort further, The Times took three additional steps during the fall.

First, we expanded our full-time staff of nine education writers by adding a new position solely devoted to coverage of reading-related issues.

Second, we added to our Sunday Metro section a full page devoted to reading aimed at parents, teachers and other adults who care for children. Each week it includes a main story that looks at some aspect of teaching reading—a school, a curricular issue, new research, etc. In addition, the page includes several features: a column of advice from reading experts for parents, a list of children’s book events localized for each part of our circulation area, a list of recommended children’s books prepared by local librarians, and a short essay by a prominent person about what first turned him or her on to reading.

Finally, as part of a previously planned redesign of our lifestyle section, Southern California Living, The Times added a page aimed at children—The Kids’ Reading Room—that is designed to encourage elementary school children to read. A prominent feature of the page is a serialized short children’s story that runs each week.

As those editorial efforts have rolled out, the business side of the paper has continued its efforts to plan the Reading by Nine campaign.

Some elements of that plan already are in place. Willes and other senior Times executives have made Reading by Nine the focus of speeches to scores of community organizations, business groups and the like, urging them to lend their help to book drives, tutoring programs and other efforts aimed at helping children learn to read. The Reading by Nine task force has met with community organizations from across the region to discuss strategies for improving the schools. The task force has also hosted several meetings of education officials from around the region, providing a forum in which they meet with literacy experts from the federal and state governments, academia and elsewhere. Newsroom personnel do not take direct part in those sessions, but stay informed about the task force’s efforts. This summer, the paper plans to host a regional reading conference to build on this work.

The campaign has clearly made a mark on the public agenda. Newly elected Governor Gray Davis, for example, has declared Reading by Nine one of his top official priorities and has proposed legislation to a special session of the Legislature to enhance the state’s teaching of reading.

By now, Reading by Nine has become institutionalized in the newsroom. Editors and reporters, knowing that stories about reading are a priority for the paper, keep an eye out for ideas and are quick to offer suggestions. Their ideas will be needed. While the paper’s initial announcement declared a five-year commitment, further involvement has proven once again that school reform is not a sport for the short-winded. The effort to ensure that our schools are properly teaching every child to read will be a priority at The Times for at least a decade.

Photo by Luis Sinco, The Los Angeles Times.

Photo by Wally Skalij, The Los Angeles Times.

David Lauter is the Specialist Editor of The Los Angeles Times, responsible for the paper’s coverage of education, science, medicine, religion, law and the environment. He has previously served as National Political Editor and was White House correspondent from 1988-90 and 1992-94.