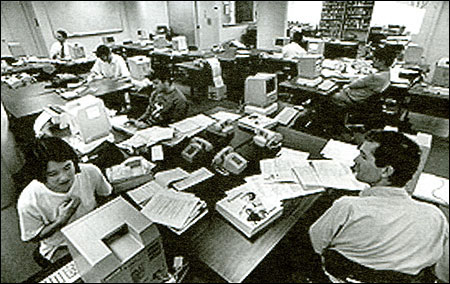

A newsroom for journalism students. Photo courtesy Medill School of Journalism.

Most of us know the frustration of desire outpacing ability. But what about coping with the reverse? What happens if you decide you don’t want to live up to your potential?

The top is what we’re all supposed to be gunning for. The best and the brightest. In America, we don’t celebrate anything less. To aim elsewhere is considered a waste of talent.

Growing up in West Virginia, the top of anything but the next mountain seemed to me remote and unlikely. Yet from the time I wrote my first story for my college paper, The Parthenon, editors and colleagues have assured me that I could go as far as I wanted in the journalism business. They meant, of course, the top. It was understood that I should want it, so I did. Fifteen years later, I’m still wrestling that well-intended prophecy.

For a reporter, the top is a vague and shifting arena marked by only a handful of immovable icons—The New York Times, The Washington Post, etc. But tethered always to this notion of moving into the journalistic stratosphere is the awareness that it takes more than just talent to do so. It requires complete subservience to the goal. In the deliciously cynical undercurrent of newsrooms, it can be a matter of pride to have one’s life in shambles, but still be destroying the opposition.

At 23, my greatest fear was never escaping West Virginia and missing my shot at journalistic greatness. Since then, I’ve spent four years at an afternoon daily in Charleston covering politics, three years teaching reporting in Hungary, and two years as a freelancer in San Francisco writing dull articles about high-risk insurance products and the computer trade.

Today, at 33, poised finally to take that shot after a decade of rambling, I am hesitant to squeeze the trigger. The problem is that in the last 10 years I learned there are things as important to me as my career; maybe some that are more important.

Raising such questions makes me feel like a heretic in the halls of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, a veritable mill for journalistic gods and goddesses. My teachers here—many of whom have made the stratospheric sacrifices—are echoing editors past with their shiny predictions for my future in this business. And why not? Surely one comes to Columbia to be a part of all that.

The end of the millennium has people in reflective mode. Friends say, “Do what makes you happy.” But would they understand if my happiness doesn’t include the high-octane career we’ve all envisioned for me? How about a summer of cooking camp in Italy instead, or a couple of years squirreled away somewhere writing another novel? What if my greatest happiness means starting a family and actively raising the kids? Would they accept that as a mark of professional happiness? Would I?

It’s not that one can’t work in the stratosphere and do all these things, too. Some people manage it. But I don’t think I can. I know from my newspaper days that reporting consumes me once I commit to it. My most self-destructive stretch thus far was when I was giving 12 to 14 hours a day to a newspaper. I drank more, ate poorly, exercised less and was more irresponsible in my relationships. I never read anything other than newspapers. I never spent a rainy Saturday just cooking. In the winter, it was dark when I left home and dark when I returned. I worked weekends, holidays. My entire social existence, slim as it was, was confined to my colleagues at the paper. Newspaper people are without peer, but they are not the only species worth knowing.

I loved it and hated it simultaneously. I cannot imagine making my living any other way, yet I fear its ability to devour everything else I love. Regardless, you have to reach the top before such a flexible and varied life is possible, and that’s where the real sacrifice comes unless you are a genius or celebrity. For several years now I have watched a friend’s single-minded climb up the journalistic food chain while the rest of her life goes untended. I know plenty of people who would love to be where she is, yet nothing she ever does is good enough for her. I don’t believe, through all that striving, she appreciates what she has already accomplished.

At first I watched with excruciating envy and self-loathing for not possessing similar courage and drive. Lately, though, I’ve watched with something akin to relief. There is still time for me to make wrong decisions and recover. But the weight of expectations, my own and others’, real and perceived, has me reeling. People expected me to be like my driven friend. So that’s what I expected of myself. Yet at every turn, I have opted for the path that led elsewhere, to other pleasures in other areas of my life.

When I left my newspaper job, for example, the obvious next move for someone headed to the stratosphere was to a bigger paper in a bigger market. I went instead to Hungary, where I traveled and wrote a novel that may never be seen by anyone other than those few friends I trust to be kind. It was there that I first began to question whether the lifestyle I had always envisioned for myself was something I really wanted.

I was in Eastern Europe in the early 1990’s and simply ignored my big chance to establish a toehold as a foreign correspondent. The opportunities were there and people I knew were taking them. I took, instead, cooking and language classes and spent long hours reading books I’d missed over the years. It’s something I’ve tried hard to regret since coming back home, but I’ve never been completely able.

I understand the idea that you can do good work anywhere. That this notion of big-time journalism is an internal—an individual—thing. But I only agree up to a point. If everything but my career fell away, my dream job would be the freedom to write about whatever interests me anywhere in the world. Only a precious few journalists have anything approaching such a job. And only a few publications can afford to indulge such a desire. The best of the best.

Clearly then, this desire exists somewhere in me. I came to Columbia, at least in part, to figure out exactly where this desire resides and how strongly it could burn. Perhaps, despite the beliefs of friends and colleagues, I could never reach the stratosphere, anyway, even with 10 times the drive of my driven friend. The question now is whether I’ll ever know.

So here I am, almost armed with a degree from Columbia’s J-school. My shot is clearing, and in May it will be mine to take or not. In the meantime, I am at least preparing to take it, if not as aggressively as perhaps I should given the cost of my time at Columbia. The school’s career services office provides a weekly listing of various internships and fellowships worldwide. Through this, I have applied for several two-year internships at larger papers in cities where I would like to live. I would prefer an actual staff position to an internship, but I suppose if I can’t make them want to hire me in two years, it wasn’t meant to be. And I know that the likelihood of being offered a full-time job at the end of an internship varies from paper to paper. A two-year intern stands a better chance of being hired than a summer one, but some things are beyond your control, such as the availability of a job when your time for review comes up. Still, I have more experience than most of my fellow students, and am ready for a staff position. So I will focus more intently on finding a full-time job this spring, both through career services and my own contacts.

In recent years, I have grown enamored of urban living, and plan—initially anyway—to limit my job search accordingly. If I come up empty, I will either suck it up and look to smaller markets or move back to San Francisco, land of the alternative lifestyle, and try to string together a living that allows for many loves. I may ultimately choose the latter regardless, but for some reason the lure of the stratosphere persists. Maybe it’s habit, or maybe it’s the proximity that Columbia affords.

Another friend fled the drive to the stratosphere when she was about my age and moved outside the city to seven acres and a dog. From this bucolic base, she tends her extensive garden, writes the freelance stories she wants and pays the bills with a handful of steady corporate editing gigs. She takes great pleasure in the fact that corporate America is subsidizing her radical journalism.

Do what makes you happy. If only it were that easy.

William Brent Cunningham graduated from Marshall University with a degree in journalism and a master’s degree in comparative politics. He worked for four years at The Charleston Daily Mail and taught reporting at the American Journalism Center in Budapest before arriving at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism.