This coffee-table book, the first by and about The Associated Press as an institution in 66 years, apparently was edited by committee, or perhaps by anonymous editors in turns. Whoever was hands-on responsible, he/she/they faced the problem of pulling together thousands of anecdotes, hundreds of claims of glory, and a few confessions of error. Moreover, much of the material had already been published.

Thus it made little sense to write another history of the wire service, merely bringing its predecessor, “AP: The Story of the News,” by Oliver Gramling (1940), up to date. Instead of a chronology, those in charge decided to organize the book around the theme of how AP correspondents and photographers got their stories. The 12 chapters, each written by a staffer, are based on subject matter, ranging from war, which gets two chapters, to sports.

Most, but not all, of the time this device works, with surprisingly little slopover from one chapter to another. When it does work, the passages demonstrate reportorial ingenuity. In 1903, Salvatore Cortesi worked out a code system to get around a two-hour ban on reporting the death of Pope Leo XIII. In nine minutes, New York AP flashed the news around the world, beating even the Italian press. Cortesi used friendship with a well-placed source, the pope’s personal physician, to provide intimate details of the pontiff’s last minutes.

Codes are dangerous. In 1935, an AP Teletype operator secreted in a New Jersey courthouse attic misread a code and filed a flash: “Verdict Reached Guilty and Life” in the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of air hero Charles A. Lindbergh’s baby. Some newspapers and radio stations used the report before AP could correct the wording to the death penalty.

Friendship, even a professional relationship, is an obvious source of beats, but it also raises the question of neutrality—look at Bob Woodward of The Washington Post and his struggle in dealing with Deep Throat. “Breaking News” tells how the “passion, tumult, intimacy and shared confidences” between reporter Lorena Hickok and Eleanor Roosevelt compromised the AP reporter. Roosevelt showed Hickok the text of the President’s 1933 inaugural speech at a dinner the night before he gave it, but Hickok never thought of using it—with its ringing “we have nothing to fear” exhortation—in advance for an exclusive.

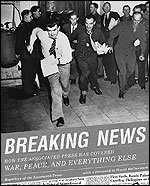

Getting to the telephone first has long made the difference between leading the pack or running second. The book’s cover photograph shows Wes Gallagher, later president of AP, dashing for the phone to report the verdict at the Nuremberg war crimes trials on October 1, 1946. He used an old trick; his wife, Betty, held the line open for him.

Merriam Smith, long the United Press chief White House Correspondent, used another stratagem when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Riding in the front seat of the fourth car in the presidential motorcade, Smith, at the first sound of shots, grabbed the mobile phone hanging from the dashboard just in front of him. Smith called his office, dictated news of the shooting, and refused to give the phone to Jack Bell of AP, who was riding in the rear seat. Smith delayed even further, insisting that the story be read back to him. When Bell finally got the phone, it went dead; apparently Smith broke the connection.

Of course, such ploys are no longer necessary with every reporter carrying a cell phone, BlackBerry and computer.

Ingenuity and Perseverance

What, then, is the value of “Breaking News” to journalists today? One of the important lessons is its reinforcement of an old one: keep after sources, don’t give up. Before the body of the Lindbergh baby was found and the world wondered his fate, AP’s Francis A. Jamieson sent two reporters to a state police news conference as a “decoy” while he called New Jersey Governor A. Harry Moore. But Moore had left his office and was on his way home. Jamieson kept dialing, finally reaching Moore, and asked him to check with the state police. While Moore called the police, Jamieson opened a second line to the national news desk. A few seconds later Moore shouted to Jamieson: “I have sad news for you. The Lindbergh baby has been found dead.” Newspapers with Jamieson’s story were on the street before the state police announcement more than an hour later. Other reporters accused the governor of favoritism, but he replied that Jamieson was the only reporter who had called him. “He caught the train,” the governor said. “The others stood on the platform and watched it go by.”

An AP beat reporter’s persistence on another big story confirms the lesson. Harold Turnblad, in the Seattle bureau, was assigned to follow the flight of Wiley Post, a record-breaking pilot, and Will Rogers, the humorist, in Alaska in 1935. Based on information from the Signal Corps in Alaska, Turnblad sent out a flash on their plane’s crash near Point Barrow, but in Washington the War Department questioned the story. “You got it straight,” a Signal Corps captain told Turnblad when he checked back. “You’re the only one I called because I didn’t have the other fellows’ numbers, and your office kept calling through the night.”

Another lesson is to scream if the editor screws up. In 1970, AP editors in New York deleted from a Peter Arnett story an account of GI looting wrecked stores in a rubber plantation during an “incursion” into Cambodia. Foreign editor Ben Bassett, concerned about domestic tensions after the killing of four student war protestors at Kent State University, sent a message to the Saigon bureau saying that stories should be “down the middle and subdue emotions” and added, “Let’s play it cool.” Arnett shot off an angry message to Wes Gallagher, AP’s general manager, that he had been “personally and professionally” insulted. Gallagher ordered the material restored to the story.

While “Breaking News,” as its title indicates, stresses the demand for getting the news first without sacrifice of accuracy, The Associated Press’s finest performance, certainly in recent times, came with its refusal to be pushed into a story. Early returns from the 2000 presidential election led the AP and the television networks to call Florida, if not the White House, for Vice President Al Gore, only to pull back. Then the networks called the election for George Bush. But AP advised newspaper editors, many of them pushing for a decision, that Bush’s lead was dwindling in Florida. It never did call the election, which ultimately was decided by the Supreme Court.

The Associated Press is rightfully proud of its accomplishments and never lets the reader forget it is the leading news agency in the world. Yet “Breaking News,” by its very title, indicates the limited impact of this great organization. Major advances in our understanding of the world come not from two-minute beats on spot news but from careful, time-consuming reporting. By far most of these stories are published in big-city newspapers, especially The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times. For these papers, The Associated Press is a backup to fill holes in coverage or a tip sheet of where to send their own reporters.

As a corollary, much of the fine work done by the AP is featured primarily in smaller papers. Even in those papers the AP story is often pushed out, no longer by United Press, as in the old days, but by the big-city news services, like those of The New York Times and The Washington Post.

The Internet adds another dimension to AP’s challenge. Online demands spot-news speed. Thus the challenge to AP is to meet the needs of all the media—of newspapers, large and small, or radio or television, and of the Internet-oriented who want the news sent to their Web sites, their desks, and their cell phones.

“Breaking News” scarcely touches on the digital era. As Walter Mears, who witnessed 45 years of change as one of the best reporters in the country, puts the problem in the final chapter of this history, “Online news delivery simply exploded; it was a matter of getting aboard or being rolled over.”

Despite resistance from holdout publishers—remember the wire service is a co-op financed primarily by assessments based on newspaper circulation, which has been falling—The Associated Press is aboard. The question remains: Will it travel first class or ride in the caboose?

Robert H. Phelps, retired editor of Nieman Reports, learned to respect and occasionally beat The Associated Press while a cub reporter with United Press Associations in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in the 1940’s.

Thus it made little sense to write another history of the wire service, merely bringing its predecessor, “AP: The Story of the News,” by Oliver Gramling (1940), up to date. Instead of a chronology, those in charge decided to organize the book around the theme of how AP correspondents and photographers got their stories. The 12 chapters, each written by a staffer, are based on subject matter, ranging from war, which gets two chapters, to sports.

Most, but not all, of the time this device works, with surprisingly little slopover from one chapter to another. When it does work, the passages demonstrate reportorial ingenuity. In 1903, Salvatore Cortesi worked out a code system to get around a two-hour ban on reporting the death of Pope Leo XIII. In nine minutes, New York AP flashed the news around the world, beating even the Italian press. Cortesi used friendship with a well-placed source, the pope’s personal physician, to provide intimate details of the pontiff’s last minutes.

Codes are dangerous. In 1935, an AP Teletype operator secreted in a New Jersey courthouse attic misread a code and filed a flash: “Verdict Reached Guilty and Life” in the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of air hero Charles A. Lindbergh’s baby. Some newspapers and radio stations used the report before AP could correct the wording to the death penalty.

Friendship, even a professional relationship, is an obvious source of beats, but it also raises the question of neutrality—look at Bob Woodward of The Washington Post and his struggle in dealing with Deep Throat. “Breaking News” tells how the “passion, tumult, intimacy and shared confidences” between reporter Lorena Hickok and Eleanor Roosevelt compromised the AP reporter. Roosevelt showed Hickok the text of the President’s 1933 inaugural speech at a dinner the night before he gave it, but Hickok never thought of using it—with its ringing “we have nothing to fear” exhortation—in advance for an exclusive.

Getting to the telephone first has long made the difference between leading the pack or running second. The book’s cover photograph shows Wes Gallagher, later president of AP, dashing for the phone to report the verdict at the Nuremberg war crimes trials on October 1, 1946. He used an old trick; his wife, Betty, held the line open for him.

Merriam Smith, long the United Press chief White House Correspondent, used another stratagem when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Riding in the front seat of the fourth car in the presidential motorcade, Smith, at the first sound of shots, grabbed the mobile phone hanging from the dashboard just in front of him. Smith called his office, dictated news of the shooting, and refused to give the phone to Jack Bell of AP, who was riding in the rear seat. Smith delayed even further, insisting that the story be read back to him. When Bell finally got the phone, it went dead; apparently Smith broke the connection.

Of course, such ploys are no longer necessary with every reporter carrying a cell phone, BlackBerry and computer.

Ingenuity and Perseverance

What, then, is the value of “Breaking News” to journalists today? One of the important lessons is its reinforcement of an old one: keep after sources, don’t give up. Before the body of the Lindbergh baby was found and the world wondered his fate, AP’s Francis A. Jamieson sent two reporters to a state police news conference as a “decoy” while he called New Jersey Governor A. Harry Moore. But Moore had left his office and was on his way home. Jamieson kept dialing, finally reaching Moore, and asked him to check with the state police. While Moore called the police, Jamieson opened a second line to the national news desk. A few seconds later Moore shouted to Jamieson: “I have sad news for you. The Lindbergh baby has been found dead.” Newspapers with Jamieson’s story were on the street before the state police announcement more than an hour later. Other reporters accused the governor of favoritism, but he replied that Jamieson was the only reporter who had called him. “He caught the train,” the governor said. “The others stood on the platform and watched it go by.”

An AP beat reporter’s persistence on another big story confirms the lesson. Harold Turnblad, in the Seattle bureau, was assigned to follow the flight of Wiley Post, a record-breaking pilot, and Will Rogers, the humorist, in Alaska in 1935. Based on information from the Signal Corps in Alaska, Turnblad sent out a flash on their plane’s crash near Point Barrow, but in Washington the War Department questioned the story. “You got it straight,” a Signal Corps captain told Turnblad when he checked back. “You’re the only one I called because I didn’t have the other fellows’ numbers, and your office kept calling through the night.”

Another lesson is to scream if the editor screws up. In 1970, AP editors in New York deleted from a Peter Arnett story an account of GI looting wrecked stores in a rubber plantation during an “incursion” into Cambodia. Foreign editor Ben Bassett, concerned about domestic tensions after the killing of four student war protestors at Kent State University, sent a message to the Saigon bureau saying that stories should be “down the middle and subdue emotions” and added, “Let’s play it cool.” Arnett shot off an angry message to Wes Gallagher, AP’s general manager, that he had been “personally and professionally” insulted. Gallagher ordered the material restored to the story.

While “Breaking News,” as its title indicates, stresses the demand for getting the news first without sacrifice of accuracy, The Associated Press’s finest performance, certainly in recent times, came with its refusal to be pushed into a story. Early returns from the 2000 presidential election led the AP and the television networks to call Florida, if not the White House, for Vice President Al Gore, only to pull back. Then the networks called the election for George Bush. But AP advised newspaper editors, many of them pushing for a decision, that Bush’s lead was dwindling in Florida. It never did call the election, which ultimately was decided by the Supreme Court.

The Associated Press is rightfully proud of its accomplishments and never lets the reader forget it is the leading news agency in the world. Yet “Breaking News,” by its very title, indicates the limited impact of this great organization. Major advances in our understanding of the world come not from two-minute beats on spot news but from careful, time-consuming reporting. By far most of these stories are published in big-city newspapers, especially The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times. For these papers, The Associated Press is a backup to fill holes in coverage or a tip sheet of where to send their own reporters.

As a corollary, much of the fine work done by the AP is featured primarily in smaller papers. Even in those papers the AP story is often pushed out, no longer by United Press, as in the old days, but by the big-city news services, like those of The New York Times and The Washington Post.

The Internet adds another dimension to AP’s challenge. Online demands spot-news speed. Thus the challenge to AP is to meet the needs of all the media—of newspapers, large and small, or radio or television, and of the Internet-oriented who want the news sent to their Web sites, their desks, and their cell phones.

“Breaking News” scarcely touches on the digital era. As Walter Mears, who witnessed 45 years of change as one of the best reporters in the country, puts the problem in the final chapter of this history, “Online news delivery simply exploded; it was a matter of getting aboard or being rolled over.”

Despite resistance from holdout publishers—remember the wire service is a co-op financed primarily by assessments based on newspaper circulation, which has been falling—The Associated Press is aboard. The question remains: Will it travel first class or ride in the caboose?

Robert H. Phelps, retired editor of Nieman Reports, learned to respect and occasionally beat The Associated Press while a cub reporter with United Press Associations in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in the 1940’s.