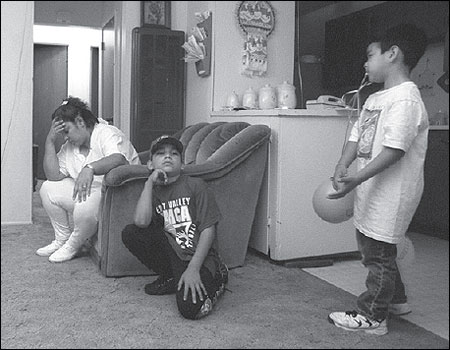

Pauline Flores takes a rare moment to rest between working all day and her sons’ basketball practice. She had just begun working as a pediatrician’s intern, a “job” for which she received no pay. From the series “Making Welfare Work.” Photo by Judith Calson/The San Jose Mercury News.

Throw out the book on welfare. Junk that Rolodex. Learn some Spanish. When it comes to covering welfare reform’s effects on U.S. Latinos, journalists will have to step beyond the anti-poverty beat. To explain what’s going on, they’ll also need to know the nasty cultural politics of immigration, race and ethnicity.

You didn’t think the federal 1996 welfare law was only about work, responsibility and dignity, did you?

For a sizable number of Latino immigrants, it was immigration reform in disguise. Congress had two ideas in mind. One was to pay for welfare reform for American citizens by cutting assistance to immigrants. The other idea was to persuade “undesirable” immigrants to go home and discourage others from coming.

For example, let’s look at Ofelia M. I met with her at a nonprofit clinic in Palo Alto, California, not long after President Clinton signed the welfare law. She and her husband had left Mexico in 1994 to clean offices and houses in the cradle of Silicon Valley. With a monthly income of $900, they could barely meet their rent and pay for basic necessities. When she became pregnant and needed prenatal medical care, she went to the clinic for checkups and to receive $50 in food coupons from a federal nutrition program.

The 1996 welfare law gave the states a choice on those coupons. A state can decide to either end eligibility for undocumented women, or approve its continuation. Either way, it wouldn’t cost the state a dime. The coupons are entirely funded by the federal government.

A no-brainer decision?

Well, no. Pete Wilson, the Republican governor of California at the time, threatened to cut off the program to undocumented mothers. He relented only after intense political pressure.

Before Wilson backed off, I asked Ofelia in Spanish if she would return to Mexico if she were disqualified from the program. Ofelia smiled. She looked at her daughter, an American citizen by birth. “No, we wouldn’t go back,” she told me. “We have to think about her and our family.”

The welfare law also allows states to eliminate federal food stamps for legal and illegal immigrants. Wilson managed to eliminate food stamps for immigrants who have arrived since 1996.

More recently, The New York Times reported on how New York state is asking applicants for food stamps for proof of citizenship and immigration status—as permitted by the welfare reform law. While their American-born children should qualify, many undocumented mothers aren’t applying out of fear of deportation. If the most important part of the news is setting it accurately within its broader context, then we can’t write about Latinos and welfare without writing about immigration.

We can trace the federally legislated welfare mandates involving immigrants back to the passage of California’s Proposition 187. Passed in 1994, the measure was a masterful piece of political scapegoating. Prop. 187 maintained that California’s generous welfare system and schools were a magnet for illegal immigrants looking for a free ride. Never mind that illegal immigrants did not qualify for basic welfare, formerly called Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or for non-emergency Medicaid. Among other things, Prop. 187 attempted to abolish public education and health services to undocumented children and adults.

After 18 years of reporting on welfare and immigration policies, I have concluded that a lot of Californians were genuinely worried about the fiscal costs of immigration. But that’s not all. As the number of Latinos and Asians grows, many Californians feared losing their status as the dominant culture in the state. Either way, the majority of voters believed that the state’s generous welfare system was a magnet for immigrants, legal or illegal, and Prop. 187 passed.

While a federal district court quickly and decisively declared most of Prop. 187 unconstitutional, social conservatives in Congress picked up the idea of using welfare reform to control the border.

Now, welfare reform was complicated enough. With immigration in the picture, reporters—who were conscientious about telling the entire story—had to chase after welfare and immigration sources at the same time. But you know what? Nobody really wanted to hear it.

Let’s face it. The public didn’t want to bother with the mechanics of welfare reform. It perceived American welfare recipients as people who got something for sitting at home doing nothing while they had to work. If the public saw citizens on welfare that way, imagine what they thought about immigrants who were on welfare.

The news media’s great failure in welfare coverage has been in following the policy debate and not the people. The result was enduring stereotypes, such as the Cadillac-driving African-American welfare queen. Now we have the brown-skinned illegal immigrant crashing the border and the legal immigrant milking his green card for all it’s worth.

Hopeless optimist that I am, I say we look on the bright side. In our coverage of welfare reform, we journalists today find ourselves just as smart or as stupid as those welfare researchers and think tanks whose job it is to evaluate what is happening in the wake of welfare reform. Advantage, us.

That’s because the new welfare law basically lets states do whatever each one decides to do. The national think tanks that have served journalists well as ready sources, from the liberal Urban Institute to the conservative Heritage Foundation, can’t possibly keep up with 50 versions of welfare reform.

I think new welfare experts will emerge at local colleges, universities and philanthropical foundations. And though these experts might not bring the sophistication of analysis that well-funded think tank studies do, they will be able to offer different and important levels of insight. They might not be able to tell what’s happening nationally, but they’ll know what’s happening closer to home. Of course, we will still get sweeping, nationwide looks at welfare reform, but they won’t be of much help to reporters unless they are able to find a relevant local angle.

Here’s an example: An Associated Press survey released this past March showed that whites are getting off welfare faster than minorities. Among the findings for Latinos on welfare:

- Sixty-four percent lacked a high school diploma, compared with 43 percent of blacks and 30 percent of whites.

- Only one-third of Latinos worked at some point during the year, compared with one-half of whites and blacks.

- Sixty percent of Latinos and 64 percent of blacks lived in a central city, compared with 29 percent of whites.

It was the kind of survey that academics might spend several years producing, then dish out the results to waiting journalists, who would write another perfunctory story about another academic welfare finding. But because journalists got these fresh survey results dumped in our laps, why should we wait for somebody else to come up with an explanation about its meaning? Why not assign reporters to look closely at how welfare reform among Latinos is affected by the policies of their local schools and by the kind of opportunities presented by their local job markets? Why not follow a number of Latinos for a year or more as they leave welfare and enter the work force and use their experiences as the crux of our reporting?

That brings up another issue involving welfare reform. This transitory time won’t last long. The real story will be what happens to former recipients in job markets for the rest of their working lives. Reporters on traditional anti-poverty beats will have to become experts on the ability of local economies to absorb all these new, mostly unskilled workers and on tracking what happens to the range of employees—former welfare recipients as well as long-time workers—who are working in low-wage jobs.

And when reporters look at Latinos in this picture, they will end up with a panoramic view as complex as the American landscape. Welfare reform for Puerto Ricans in Hartford, Connecticut, where I reported for eight years, will be very much the story of an undereducated people, isolated in a poor city from jobs that are being newly created in white suburbs. The unique dimension, however, is that this population’s traditionally high rate of moving between the mainland and the island may hamper participation in long-term job training and education programs for welfare recipients.

Reporting on welfare reform for Mexican-Americans in rural South Texas will reveal entirely different stories. With unemployment as high as 20 percent, and food stamp cutoffs to legal immigrants and underemployment for citizens coming off welfare, border community economies could be damaged and social services stretched too thin. In Los Angeles, poor Mexican-Americans coming off welfare may find themselves competing with African-Americans and immigrant Asians and Latinos for low-wage jobs with little or no health benefits. A race to the bottom in Los Angeles, my hometown, would be a dangerous thing. I’ve seen two major race riots there in my lifetime. I’d rather think of new opportunities that might be presented by welfare reform in covering this story.

Welfare reform was a blunt, national instrument with an anti-immigrant mean streak built in. I’m sure it’ll play out that way in some states. But I’m also confident that other states will resist the urge to single out immigrants for harsher treatment than others trying to move off welfare.

The point is, nobody is in a better position to track the progress and inequities of welfare reform and to challenge ethnic stereotypes than journalists working in local newsrooms.

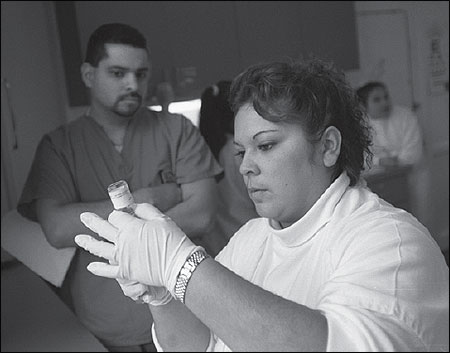

An instructor observes Flores preparing a needle in her medical assistant course. From “Making Welfare Work.” Photo by Judith Calson/The San Jose Mercury News.

Joe Rodriguez, a metro columnist for The San Jose Mercury News, is a 1998 Nieman Fellow. He is a co-winner of the 1998 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism for The Mercury News’s opinion page series, “Making Welfare Work,” and also won a 1994 Unity Prize from Lincoln University for a series of editorials and columns on immigration issues.