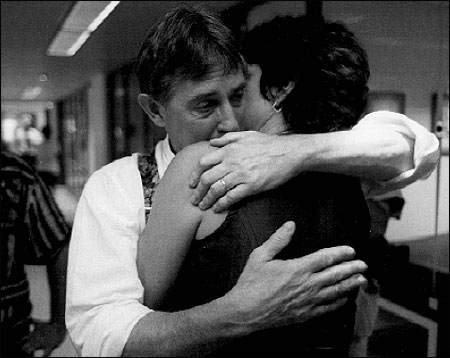

New York Newsday Editor Donald Forst consoles photographer Erica Berger on closing of the paper. Photo by Mitsu Yasukawa, courtesy of New York Newsday.

[This article originally appeared in the Spring 1996 issue of Nieman Reports.]

The question for the nation’s newspapers is as stark as it is simple: Will they survive?

In a few years, most newspaper readers will live in homes served by the electronic equivalent of a giant watermain through which will roar a Niagara of information. They will have access to an almost limitless supply of data, seductively presented. To compare today’s on-line offerings to what is soon to come is to compare hieroglyphics and papyrus to Time magazine.

So it is little wonder that newspaper companies are worried and confused— even panicky.

Whether the nation’s newspapers save themselves—and they can—lies almost entirely in the hands of their owners and top executives, who have the power to decide how money is spent, and in what amounts. These are shrewd and intelligent people, most of whom believe they are journalists, if only tangentially. They are also serious about their business and are guided by reason and pragmatism.

Therefore, it is all the more stupefying that the nation’s newspaper executives are engaged at this critical moment in undermining the very thing that is the absolute essential key to their survival.

The newspaper industry is binging on its seed corn.

To use the business jargon that is now ubiquitous from the executive suite of General Motors to the publisher’s office of The Daily Bugle, the “core competency” of newspapers—that service that no one else can do better—is reporting the news. Yet throughout the nation, news budgets are being squeezed, news staffs depleted, news travel curtailed, news holes reduced, and the news itself dumbed down.

It is as though General Motors decided to compete with Japan by making a few cosmetic changes to mask the fact that the cars were actually less reliable and less innovative—and at the same time charging more for them. Any businessman would view such a strategy as suicidal, but that essential business plan is now in place at newspapers all over the nation.

For instance, at Knight Ridder’s Philadelphia Daily News, the news staff has been cut and the news budget is so tight that only selected phones may be used to dial directory assistance, according to The Washington Post. The price of the paper, however, just increased 20 percent.

“To raise the price and cut content at the same time is beyond frustrating,” Zachary Stalberg, the News’s editor, told the Post.

At the Los Angeles Times, where the news budget is under enormous pressure, a sign showing the current Times Mirror stock price is positioned so arriving employees can see it, the better to understand why it is necessary that reporters no longer travel to sporting events that they used to cover.

But Times Mirror and Knight Ridder are hardly alone in seeking increased profits by reducing news costs. A recent survey of the nation’s top editors found that the major reason for their increased levels of stress is “lack of adequate staff, budget considerations, and a heavier workload,” according to the Associated Press Managing Editors Association.

What is being undermined is the newspaper industry’s core competency. As management gurus say, a core competency is what allows any business to exist. It is the product or service that customers perceive to have value. It is what motivates them to spend their money. At a dry cleaner, the core competency is doing a good job cleaning clothes. If you are the only dry cleaner in town, you don’t have to be a great dry cleaner, but if another shop opens down the street, you have to get better fast. In that sense, Mark H. Willes, the Chief Executive of Times Mirror Co., is absolutely correct in comparing the Los Angeles Times to a box of Cheerios. While brand loyalty can carry a product for a while, in the long-term Cheerios must be better than other toasted oat loops to survive. A lot better, if the rival is much cheaper. The Los Angeles Times and all other newspapers are no different, except that their fundamental product is news.

The real risk within the newspaper business is that smart people like Mark Willes and Tony Ridder, Chairman of Knight Ridder Inc., and many other industry leaders seem maddeningly blind to the fact that expanded, enhanced news coverage is the only thing that assures the long-term survival of the nation’s newspapers. They dismiss the concept as impractical, based on an outdated, romantic ideal of what newspapers should be.

But this is not a moral issue. It is a business one.

It is news that will attract customers, who in turn will attract advertisers as well as clients for the vast array of periphery businesses newspapers are now entering, from delivering magazines and custom publishing to audio-text and fledgling on-line services to selling coffee mugs emblazoned with the newspaper’s flag. But without news dominance, these “added-value” ventures will wither.

If this long-term strategy is really so obvious, why don’t these people act to bolster and expand their core competency while newspapers are still the premier news organizations in their markets? Why are they willing to waste such an invaluable—but increasingly shaky—advantage?

Because of money, of course. The glorious decade between 1977 and 1987 may have ruined the newspaper business.

It was a decade of unprecedented profitability at newspapers. The Inland/ INFE National Cost & Revenue Study for papers of 50,000 circulation reported average profits of over 20 percent in 1986; the profit margins were double that or more at some particularly bottom-line chains. Owning a newspaper seemed almost foolproof. Newspaper unions had been generally neutralized, and high technology allowed huge savings in production costs. Most newspapers were the only one in town, and the Reagan economy was booming.

Then came the 1987 stock market crash, to be followed over the next several years by the worst-ever advertising recession.

Many of the nation’s major newspaper companies are publicly owned, and their stockholders had little taste for dwindling profits after a decade of double-digit annual increases. Wall Street’s baying analysts considered profit margins short of mid-80’s levels aberrant and temporary. Management generally agreed, and the newspaper industry went through five years of belt-tightening in every area, including news.

And public newspaper companies were not the only ones addicted to 20- plus percent profit levels. Many privately held and family-owned newspapers were operated just as voraciously, and often much less competently, than the public ones.

When the crunch came and revenues plummeted, it was only prudent to cut some expenses, including news costs. Newspapers are a business, and their owners should not consider them to be nonprofit public services. Solid business success is the surest guarantor of editorial independence.

But a solid profit is not the same thing as a 20 percent profit. And after a long round of stringent belt-tightening, many of the nation’s newspapers are engaged in yet another round, this time justified by higher newsprint prices that surged after being artificially low during the advertising drought.

The bitter medicine of newsroom cost cutting, hold-downs and hiring freezes is nothing new to newspapers. But this time the situation is different, even compared to 1987. This time, the patient might die.

Newspapers are a cyclical business, and newsroom cost cutting usually occurs when business is bad. Newspapers have been able to get away with squeezing the news product because there was no real competition in that particular area.

There was plenty of competition on the advertising front: from radio, then television, then local cable operations that even the smallest markets could not escape and which made it possible for every automobile dealer to fulfill the fantasy of appearing on television. In recent years, direct mailers have been the most ferocious rival, and they have been joined in their assault on newspaper advertising by the U.S. Postal Service. The result has been a price war on preprinted advertising circulars that has hit newspaper advertising revenues hard. Locally owned businesses are increasingly rare, and that also penalizes newspapers. Some big retailers tend to look strictly at price and have no personal stake in supporting the local paper.…

Add to these woes the surge in newsprint prices that began in 1994 and, in some areas, the still-depressed overall economy, and it is not difficult to see why newspapers are under financial pressure.

To deal with these challenges to their advertising dollars, newspapers have cut costs and found new ways to produce revenue. Traditionally, they just raised ad rates, but in such a competitive advertising environment, that solution has become very risky.

The new newspaper theory is that circulation must produce more of the revenue, which is why—despite reductions in the news hole and letting newsroom vacancies lie unfilled—many, many newspapers have increased their price in the last year or two. The market would bear it, so they did it.

What the newspaper industry has not yet grasped is that there is a rival looming that is different from radio, television, cable or direct mail. This competitor—the electronic one that is murkily referred to as “the Internet”— directly challenges the “core competency” that newspapers have enjoyed for so long with splendid and unthreatened confidence.

As a local news utility, none of the other media has ever credibly threatened newspapers. The last time newspapers had serious rivals was when there were two genuinely competing newspapers in the same town, and that sort of all-out news battling is well outside the memory of most newspaper executives these days.

The Milwaukee Sentinel staff hearing of merger with the Milwaukee Journal. Photo by Benny Sieu, © 2000 Journal Sentinel Inc., reproduced with permission.

Even in the markets where there is competition, the newspapers either carve out different niches of the total audience or participate in joint operating arrangements. There are few cities where two serious newspapers fight it out for the same reader. The New York Times does not really compete with the Daily News or the New York Post. It did compete with New York Newsday, but that ended last year when Times Mirror shut the paper down.

In the rare places where there is genuine rivalry between newspapers, the impact on news budgets is the exact opposite of the current trend.

A wonderfully telling example is the case of The Denver Post, which is owned by William Dean Singleton, one of the most profit-minded and cost-conscious publishers in the nation.

Dean Singleton’s Denver Post is in a fierce news battle with the Rocky Mountain News, flagship of the Scripps Howard chain. Over the past year, the Rocky laid off 17 managers and demoted some others, but publicly boasted that no downsizing had occurred in the news department. The Post, meanwhile, expanded its news budget as though Singleton took pride in making a lush news operation his signature.

Nothing could be further from the truth. In September, Dean Singleton acquired The Berkshire Eagle in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, one of the most distinguished small newspapers in the nation and one known for its oversized—by industry standards— news operation. Unfortunately, the paper’s owners overextended in other non-newspaper areas. It was not their handsome news operation that forced them to sell, but when they got into financial trouble they cut the news staff to 40 from a high of 62. When Singleton bought the paper, he ordered news salaries cut and the news staff further reduced. An additional 11 editorial employees left or were not offered jobs.

The bulging newsroom in Denver and the decimated one in Pittsfield make the point. Newspapers will spend what they need to spend on news in order to protect their market position. It is good, common business sense. And when they don’t have to worry about protecting their newsgathering dominance, they will apply a standard that makes 20-plus percent profit margins attainable.

The potential catastrophe for the newspaper business is that the people who lead it have not yet realized that they are in the position of The Denver Post, not The Berkshire Eagle.

Newspaper executives simply have not been willing to imagine what seems increasingly obvious: that alternative newsgathering enterprises of high quality and great breadth can be created in their own markets.

What is going to be even harder for them to swallow is that the people who report and write and edit for these new news outlets are very likely to be some of their own employees…or, more accurately, former employees. Newspaper executives seem to believe that they have a patent on newsgathering, that because local radio and television and cable are little more than headline services, no one can come into their community and simply take the news away from them.

They are wrong.

It can be done, and—in some place soon—it will be done.

As an instructive case, think of Bloomberg News. Indeed, Michael Bloomberg is probably one of the people who most fervently hopes that the newspaper industry will continue to cannibalize itself for the sake of short-term profits.

Bloomberg News was created in the last few years as an entrepreneurial venture, virtually out of the air. It is now a serious, and very aggressive, news service specializing in financial news and hungry for a bigger game.

Or consider CNN. It took vision and money to create and then suddenly it was an international institution. Now the very television networks that could easily have created CNN themselves have declared that they will try to catch up with Ted Turner.

Bill Gates is feverishly spending top dollar to recruit some of journalism’s ablest people from both print and television. Is it difficult to imagine that this man, who wants every computer in the world to run on his software, also wants his company to be the prime provider of news—including local news—in every town in America?

Is it difficult to imagine that in Anytown, USA, fledgling electronic newsgathering operations will soon emerge? After all, there is no barrier to entry other than the raw cost of paying the reporters and editors who gather and present the information over the Internet.

Is it difficult to imagine that a local entrepreneur, or an ambitious local television station, or the local version of America Online, would hire away some of the local daily’s reporters and editors by offering them a 50 percent raise and complete editorial freedom? Make no mistake, local television believes that the electronic future of local news belongs to them, and they are hiring accordingly.

And might this local information and news enterprise become a business? A real business? With no presses, no distribution costs, and even better quality reporting than the local paper if that paper has been squeezing its news?

And might not such local electronic news outlets become franchises in their own right, to be assembled into well-capitalized networks offering first-class local news as an inducement to subscribe to an on-line service? Might Bill Gates be interested in such a network? Or Bell Atlantic? Or America Online? Or The Chicago Tribune Company?

So, how can newspapers save themselves?

They must pretend they are in Denver. They must fight and claw for news with the same unquenchable energy with which they wring every advertising dollar out of their markets.

They must open their news hole, hire good people, pay for quality, and vigorously promote the fact that they are doing all these things.

They must get ready to adapt their preeminent news machines to the electronic world, in whatever form or with whatever delivery system is required. But they must never forget that without the preeminent news machine, the electronic delivery will be to no avail.

They must make themselves as profitable and as tightly run as possible, but not by consuming their own muscle tissue. The real fat in newspaper expense is in the category listed on the Inland Cost and Revenue Study as “G&A,” for general and administrative. The most recent study shows that between 1959 and 1994, the percentage of the annual expense devoted to G&A—everything from accounting to health plan management to janitorial services—ballooned from 21 to 33 percent. That is more than twice the percentage of any other expense category, including news and newsprint. G&A functions don’t put a story in the paper or sell an ad. Some of these functions can be contracted to outsiders, who perform such work as their core competency and could do it more cheaply and as well. Certainly, if newspapers need to cut costs, here is an area ripe for the squeezing.

They must draw comfort from the knowledge that their greatest defense is the creation of an overwhelming offense. And they must remember that the absence of an electronic rival in their particular market is not cause for complacency. Newspaper owners have long known that the world is full of people who would love to take their advertising away from them, and now they must extend that wisdom to include the certain conviction that the world is also full of people who want to eat their lunch as newsgatherers.

And they must decide to settle for a long future with lower profit margins rather than a much shorter future with the 1980’s-level profit margins that, for the present, can still be wrung out of most newspapers.

Some newspapers will understand where their long-term interests lie and will invest in creating a local version of a news juggernaut. For them the electronic future is not a terror, but a sweeping opportunity.

Instead of feasting on their seed corn now, these shrewd few will be able to gorge later…on the markets of their less-wise newspaper colleagues.

Alex Jones, a 1982 Nieman Fellow, is in the fourth generation of a Tennessee newspaper family that, beginning with his great-grandmother and grandmother in 1916, still publishes the family paper, The Greeneville Sun. Alex began his career at The New York Times in 1983. His series on the fall of the Bingham newspaper dynasty in Louisville won a 1987 Pulitzer Prize. He and his wife, Susan Tifft, later coauthored a book on the Binghams, “The Patriarch.” Alex left the Times in 1992 to work with Susan Tifft on the first biography of the Ochs/ Sulzberger family, which is scheduled for publication in 1998.