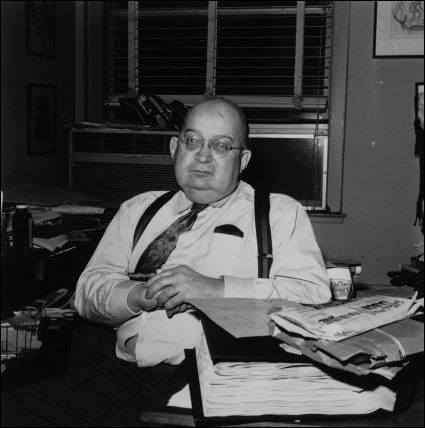

A.J. Liebling. Photo courtesy of UPI/Corbis-Bettmann.

[This article originally appeared in the March 1963 issue of Nieman Reports.]

It is a time-honored custom for the out-of-town speaker to tell you what’s wrong with newspapers. Forgive me for flouting tradition—but I don’t think there’s a goddamned thing wrong with newspapers.

I’m proud of my business and grateful to it for a satisfying life as a reporter. I’d rather cover a President than be President. I’d rather cover the county courthouse than be the town banker. I’d rather be club editor than president of a country club to which a reporter couldn’t belong.

If journalism had not rescued me from the working classes, I would today have about 40 years seniority on the Chicago and North Western Railroad. This would perhaps have permitted me to work the day shift in the train yard at Proviso yards in Chicago.

When I need some self-justification for this professional smugness, I recall as my example a man named Jack Burke, a pit boss in a Havana gambling joint. I met him during an investigation of Batista’s links with the U.S. underworld five years ago. I asked Burke how he had got into the racket, and he recalled the event with some pride.

“I used to drive a milk wagon in San Francisco,” Burke told me. “After a while I noticed that I had to work 29 days to get a day off, but that they worked the horse only every other day. That’s how I became a crap dealer.”

To belabor the point, I have never for a moment regretted the day that I had a chance to become a reporter. And my most thoughtful prayer at this stage of life is that my bosses will remain solvent and that I’ll hang on until it’s time for them to give me a gold watch and some matched luggage.

My strong feeling about a business that has been good to me makes me impatient with intellectuals who criticize the American press for its banality, its parochialism, and its imputed failure to keep our people dewy-eyed and well informed.

Frequently these intellectual discussions use The New York Times as a measuring rod for the deficiencies of us provincials.

There’s always a gaping hole in this presentation.

The New York Times is a great institution, everyone agrees. If it did not exist, the Ford Foundation would have to start one. But there’s room in this country for only one New York Times. God forbid that we could support more than one. If we ever got into an orgy of keeping well informed to the point that everyone was reading the equivalent of The New York Times, there’d be no coal dug, no yarn carded, no automobiles bolted together.

Nearly every highbrow discussion of journalism in which I’ve participated has ignored the dichotomy of the newspaper business. So long as we have a free-enterprise society, newspapering is first of all a profit and loss operation, and after that a thing of the spirit.

A. J. Liebling is the most devastating critic of the U.S. press that we know. But read Liebling, and you sense that he is still suffering from a traumatic emotional experience he had back in 1930, when some hardheaded character took a look at the account books at the New York World, decided he didn’t want to lose any more money, and killed that great institution.

The callous business judgment which killed the World also left Liebling with a lifelong bitterness. Why? Simply because Liebling, as an idealistic young man, had overlooked the fact that the romantic life of a reporter in a battered hat is impossible unless some advertising hustler in a hard hat is bringing in the sheaves.

The tiresome discussions about the role of the press in a free society could probably be deflated a little if newspapermen and their critics alike kept in mind the unique and dichotomous nature of journalism in a democratic society resting on a free-enterprise system of production.

Newspapering is a mass production, assembly-line manufacturing process, first and foremost. And like any other manufacturing process, the assembly line shuts down if the customers don’t buy the merchandise.

But there is a slight difference that makes our manufacturing business unique. And you’ll pardon me for repeating that ancient story about the debate over equal rights in the French Chamber of Deputies. When a speaker remarked that there was only a slight difference between men and women, the chamber arose as one man and shouted:

“Vive la petite difference!”

“La petite difference” in our business is this:

We are the only commercial enterprise specifically covered by a guarantee in the Constitution of the United States. I refer, of course, to the freedom of press specified in the First Amendment, a simple and well worn phrase packed both with opportunity and responsibility.

Shaken down, this is what it means:

After we have filled the forms with ad copy, with the crossword puzzle, with Ann Landers or Dear Abby, with the daily bridge hand (where north and south for some reason always get the cards), with recipes for Lenten meals, with the vital statistics, with the night police report, and with the canned material from New York, Washington and Hollywood, we find a little hole remaining in the type.

That is where comes to flower the brilliant thought you had in the shower. That is where reporters find space to report an unjust conviction, or some evidence of stealing in high places, or the preposterous utterances of some politician suffering from delusions of grandeur.

It’s that little hole in the forms, where we express ourselves, that the First Amendment was written about. The expressions of the spirit that go into that free space, sometimes noble and courageous, sometimes petty and self-serving, are the things that make “la petite difference” between us and all other manufacturing industries.

That freedom of the press of which you are custodians is precious.

And editors would be less than human if they were not at times hypersensitive about freedom of the press. They would also be less than human if they did not sometimes overemphasize the privilege of freedom enough to blur their vision of the responsibility that is part and parcel of the privilege.

I do not offer this as serious criticism of the people in our business. When editors are either hypersensitive about their rights, or insensitive to their responsibilities, a better balance is soon restored by time, events and the pressures of competition.

I think that an editor’s sense of responsibility is sometimes blunted temporarily by his personal environment, which can permit a cultural gap to develop between editors and readers. Let me explain this theory. A $20,000 editor will live in a $20,000 suburb; he will play golf and poker with $20,000 people; inevitably he will think $20,000 thoughts; with enough environmental conditioning, an editor could find a cultural gap between him and the people on the wrong side of the tracks. This cultural lag, if it exists, can betray itself in a delayed awareness, on the part of the editor, toward a fresh wave of news affecting groups outside his personal life. I think this lag was apparent in the early 1930’s, in the explosive rise of a labor movement which is now almost respectable. It has been apparent in more recent years, among some editors who have forlornly wished that this boring story of the racial crisis would just go away.

Ours is a nerve-racking business. It follows that hypersensitivity about freedom of the press appears more frequently in our ranks than does insensitivity to duty.

In 36 years as a reporter, I have had my share of personal experiences with arrogant or corrupt people who took it upon themselves to stop the flow of information. But I have difficulty getting agitated about these characters. Somehow or other the information starts to flow again. You steal it, you keep harping about it, you get legislators on your side who want their names in the paper, and they carry the torch for you.

To me, a much more serious problem than suppression of news by public figures is the selection of news by reporters. I have been aware of this particularly since living in Washington. There’s just too much of the world for the human mind to comprehend any more. The reporter or editor who can settle on a news budget on any given day without some secret apprehension about what he’s missing is probably a very rare bird.

On many a day when I am afflicted with this problem, I think with nostalgia of a German who was on the night desk of the old Wesliche Post in St. Louis. President Harding was on his deathbed in San Francisco. Right after the German editor had locked up his front page for the night, the AP bulletin phone rang, and a voice said:

“Flash...Harding dead.”

“Vee got enuf news already,” the editor said as he hung up.

We can all envy the stolidity of that editor. If we had it, the incidence of ulcers in our business would certainly decline.

And with that German’s sluggish self-possession, editors and reporters as a group might be slower in their wrath about threats to the freedom of the press.

We’ve had an uproar in recent weeks about news management and suppression. I hesitate to criticize the brethren in Washington with whom I share the daily burden of futility and frustration. But I think that extended residence in that insidious atmosphere tends to make many of us too touchy about what goes on amongst the federal payrollers behind closed doors.

I derived only one lasting impression from the Cuban crisis—John F. Kennedy, looking very much like Matt Dillon, one of my own heroes, walked up to the mouth of a cave and told Khrushchev to throw out his gun and come out with his hands up. The break in the tension that followed may some day appear to be the most important event of our generation. The fact that the President did this with some clever news management has failed to disturb me.

I think many of you are still upset by the Pentagon order which requires all officials in the Department of Defense to report to the Public Information Secretary the substance of any talks they have with reporters.

This sounds like implied censorship. It carries the germ of something that could be contrary to public interest.

But in fairness to Art Sylvester, formerly of the Newark News, who is Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, another side of this order should be considered.

Ever since the armed services were consolidated in 1947, with the statutory provision that the Secretary of Defense must come from civilian life, there have been flare-ups of guerilla warfare conducted by the information services of the military service branches against the civilian authority imposed upon them by law. This warfare has been carried on through the leakage of contrived stories behind the backs of civilian information officials. The purpose of these illicit leaks is generally to influence public or congressional opinion against the decisions or pending decisions of civilian authorities.

The Pentagon directive which has created controversy is quite simply a defense weapon of the civilian authorities against the furtive insubordination of the information officers of the separate service branches. Secretary of Defense McNamara, with a proper concern for morale, does not like to have this discussed publicly, but that’s the fact of the matter.

If and when a form of news management like this becomes a vehicle for concealing information to which taxpayers are entitled, I think we can be certain that somebody will break the blockade.

There’s another generally ignored fact that should be remembered when we talk of news suppression. Find me a government official with more than a handful of payrollers in his department, and I’ll find you a stool pigeon, an informant who at some time in his career wants to get even with his boss.

It may seem crude for me to stand here and plead for an honorable place in history for the stool pigeon. But let’s face it—life in our honorable profession would be more difficult without them.

This is a timely occasion, incidentally, for discussing the role of the stool pigeon in government. A significant magazine story casting scorn on Adlai E. Stevenson’s role in the Cuban crisis could only have come from some informant close to the President and the National Security Council. After noting the uproar caused by this story, I had the feeling that if Mr. Kennedy came before a group of editors again and asked them to exercise self-censorship, he would be laughed off the platform.

And now I offer a final reason for restraint in our concern about freedom of the press.

The incidents involving suppression of news are actually conflicts between mortal men and an institution.

You are the institution. You’ll be around.

The payrollers are the mortal men. In the long run, they’ve got to lose.

I doubt that many public wrongdoers have gone unpunished. At some time or another an unexpected shift in the wind topples the screen and reveals them in all their ugliness. Or the voters finally catch up with them, usually after long and painful efforts by newspapers to expose them as fakers. Whatever they do, life eventually closes in on them. And if you aren’t around to record the event, your successor will be. The important thing to remember is that you’ll have the last word.

As we enter these conflicts with public payrollers, we could gain some serenity by reminding ourselves that our adversary is probably a lot more scared than we are.

I’ll close by recalling a story about John Eastman, Publisher of the old Chicago Journal.

One day Mr. Eastman found Bob Casey, then a young reporter, full of fury about some bit of effrontery or arrogance he had just experienced with a public servant. Eastman advised Bob to simmer down.

“Bob,” he said, “I sit in my window with a bouquet of roses in one hand and a sockful of dung in the other. And my friends and my enemies pass.”

Perhaps if we remember John Eastman’s advice to Bob Casey in our recurring crises over freedom of the press, it will help us all to relax.

Edwin A. Lahey, Nieman Fellow 1939, is Chief of the Washington Bureau of the Knight Papers. This was an address to The Associated Press News Council. A request for an advance copy yielded what is said to be the only prepared text of a Lahey speech.