When I started in the newspaper business as a high school student in a small Iowa town in the early 1970s, our paper was as social as media got. The Shenandoah Evening Sentinel ran short items we called “locals,” submitted by area busybodies, telling who was visiting whom, who was ill and who had just returned from vacation. Unlike most tweeps today, our locals actually answered Twitter’s question, “What are you doing?”

I didn’t care much about that since I wanted to launch my career as an investigative reporter. But I did connect with the community through that social media newspaper. I first encountered my future wife when she called to criticize my prediction about a high school football game. (I was right.) During the next few years the Sentinel told people in and around Shenandoah about our graduations, engagement, wedding, the birth of our first son, and eventually the deaths of my father and Mimi’s parents. The newspaper connected our community like nothing else. You couldn’t imagine Shenandoah without the Sentinel.

With our children grown, Mimi and I get most of our news from links on Twitter and send our love and honey-do’s by txt msg while the local newspaper, The Gazette in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, which provides my paycheck, piles up in the recycling bin, mostly unread.

The Sentinel died in the 1990’s, about a decade after the newspaper I carried as a youth in Ohio, the Columbus Citizen-Journal, published its final edition. I was present for the final editions of the Des Moines Tribune in 1982 and the Kansas City Times in 1990. While I did manage to do lots of investigative journalism, I noticed early that newspapers have essentially been dying my whole career. So don’t count me among those who blame the current turmoil in the newspaper business on Google, Facebook, Twitter or some other digital demon.

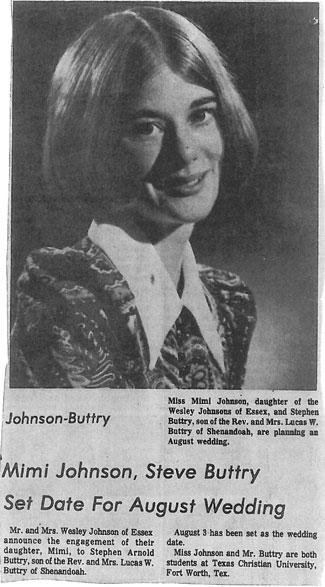

In the 1970’s Buttry’s local newspaper, The Shenandoah Evening Sentinel, published the announcement of his and his future wife’s engagement.

Digital Attempts

I encountered the prospect of a newspaper’s digital delivery of information before I heard of the Internet. A few proprietary services—America Online, Prodigy and CompuServe—were offering digital news to early adopters who had computer modems—all dial-up, of course. I was pondering such a purchase myself. As an assistant managing editor at The Kansas City Star, I attended meetings about a project called StarText. We were going to provide newspaper stories (text only) by modem the night before their publication to subscribers of the service. I suggested that we sell and install modems and show people how to use them, just as cable companies provided the equipment needed to access their service. My suggestion didn’t take root. Like most other newspaper managers, my peers and bosses at the Star thought we were in the newspaper business. While they were trying earnestly to innovate and dive into the digital stream, they failed to realize that we were really in the community connection business.

I saw a more discouraging view of the mindset of newspaper companies when I was at the Omaha World-Herald in the mid-1990’s. The publisher dismissed the fledgling Internet as a fad and our company was slow to go online and we didn’t pursue any serious innovation. When I left in 1998, I still didn’t have e-mail or Web access from my desk. Most reporters still didn’t when I returned two years later, but I negotiated to be one of the first.

When I worked at the American Press Institute (API) from 2005 to 2008, I became heavily involved in the Newspaper Next project, focused on helping newspaper companies develop business models for the digital age. Clayton Christensen, a Harvard business professor who has studied innovation in dozens of industries, partnered with API on the project. I had seen the newspaper companies I worked for as an employee and consultant make all of the errors that Christensen said established companies typically make when faced with the threat or opportunity of disruptive innovation.

We ignored competitors because we didn’t think their product or service was good enough to worry about.

We crammed our existing model into new technology rather than imagining and exploring the possibilities.

We bogged innovation down in the culture of our hidebound organizations.

As I taught the principles of innovation in Newspaper Next, I saw newspaper companies respond with limited, narrow projects that barely, if at all, changed their cultures or their business models.

Though Buttry doesn’t know of a newspaper Web site that handles engagement announcements and weddings in the way he envisioned in his Complete Community Connection blueprint, StlToday.com, the Web site of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, uses digital tools to gather and share this news.

Connecting the Community

I began to develop my own ideas to use digital tools to do some of the jobs that were essential to connecting the community when I was cutting my teeth at the Evening Sentinel. I wrote my first drafts of a vision for a new business model. When API decided not to use my work for the second Newspaper Next report in early 2008, I started looking for a newspaper company adventurous enough to give my Complete Community Connection plan a try. At this time, I was also jumping into social media, first with Flickr and LinkedIn, then Facebook. Twitter really showed me how social media were revolutionizing how the world connected. With brief comments, questions and links, I communicate daily with thousands of people, becoming so familiar with many that when we actually “tweetup,” we greet one another like old friends.

My business model and my enthusiasm for social media appealed to the executives of Gazette Communications, and I arrived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa to start as editor last June 10th. Two days later, our nation’s worst disaster since Hurricane Katrina struck my new home. Our staff has covered the flood and its recovery with a wide range of digital tools—interactive maps and databases, social media, video, multimedia, liveblogging. We are recognized as industry pioneers in the use of liveblogging and Twitter. Our digital editor, Jason Kristufek, launched and led a series of BarCamp NewsInnovation conferences around the country.

But the disaster delayed us from the crucial work of transforming our business model. On top of the national economic slowdown and the economic challenges facing the rest of the industry, our community is reeling from a crisis that damaged or destroyed a thousand businesses. We had to join the wave of newspaper companies cutting staffs. But, unlike most of our shrinking peers, our executives faced the music the next day in a live chat.

In April, I published my vision for the new business model on my blog, calling it “A Blueprint for the Complete Community Connection.” I’m now “C3 Coach” at Gazette Communications, trying to turn the vision into fact. Bloggers and tweeps responded positively to the blueprint, and it earned me a seat at the Poynter Instit

ute’s Big Ideas Conference in July.

It’s not a digital update of the newspaper, but it is a digital update of the community connection role I first learned about as a youth in Shenandoah. Yes, the model includes professional journalists who will use digital tools to tell the community’s big news in new ways. More important, we will provide the platform where the community will tell those big stories in people’s lives that connect the community in important and meaningful ways—stories of graduation, engagement, birth and death, and who’s visiting whom and who’s in the hospital. (Many days, my biggest news now arrives from CaringBridge, a customized Web site where my brother-in-law updates friends and family around the world on my nephew’s recovery from a bone-marrow transplant.)

Just as important, C3 calls for us to move beyond the collapsing advertising and subscription revenue model. Many of those community moments described above are occasions for sending a gift or flowers. We need to enable businesses to conduct those transactions and many more through C3 using credit or debit cards. We need to connect businesses with ways to target the customers they want; when a high school graduate fills in “University of Iowa” for his college choice in our Class of 2010 site, ads for campus-area restaurants and bookstores should appear, offering opportunities for grandparents to buy gift cards.

I wish I could boast of C3 accomplishments and not just the vision. Like many others, our company has spent more time and energy on reorganization than on true innovation. I get frustrated at the pace of transforming a culture focused on producing our newspaper, television broadcasts, and news Web sites. I’m going to have to pursue this as persistently as any investigative story I ever worked, with the same commitment to reaching the goal, whatever the obstacles.

Steve Buttry is C3 coach at Gazette Communications. He can be followed at twitter.com/stevebuttry or on his blog, stevebuttry.wordpress.com.

I didn’t care much about that since I wanted to launch my career as an investigative reporter. But I did connect with the community through that social media newspaper. I first encountered my future wife when she called to criticize my prediction about a high school football game. (I was right.) During the next few years the Sentinel told people in and around Shenandoah about our graduations, engagement, wedding, the birth of our first son, and eventually the deaths of my father and Mimi’s parents. The newspaper connected our community like nothing else. You couldn’t imagine Shenandoah without the Sentinel.

With our children grown, Mimi and I get most of our news from links on Twitter and send our love and honey-do’s by txt msg while the local newspaper, The Gazette in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, which provides my paycheck, piles up in the recycling bin, mostly unread.

The Sentinel died in the 1990’s, about a decade after the newspaper I carried as a youth in Ohio, the Columbus Citizen-Journal, published its final edition. I was present for the final editions of the Des Moines Tribune in 1982 and the Kansas City Times in 1990. While I did manage to do lots of investigative journalism, I noticed early that newspapers have essentially been dying my whole career. So don’t count me among those who blame the current turmoil in the newspaper business on Google, Facebook, Twitter or some other digital demon.

In the 1970’s Buttry’s local newspaper, The Shenandoah Evening Sentinel, published the announcement of his and his future wife’s engagement.

Digital Attempts

I encountered the prospect of a newspaper’s digital delivery of information before I heard of the Internet. A few proprietary services—America Online, Prodigy and CompuServe—were offering digital news to early adopters who had computer modems—all dial-up, of course. I was pondering such a purchase myself. As an assistant managing editor at The Kansas City Star, I attended meetings about a project called StarText. We were going to provide newspaper stories (text only) by modem the night before their publication to subscribers of the service. I suggested that we sell and install modems and show people how to use them, just as cable companies provided the equipment needed to access their service. My suggestion didn’t take root. Like most other newspaper managers, my peers and bosses at the Star thought we were in the newspaper business. While they were trying earnestly to innovate and dive into the digital stream, they failed to realize that we were really in the community connection business.

I saw a more discouraging view of the mindset of newspaper companies when I was at the Omaha World-Herald in the mid-1990’s. The publisher dismissed the fledgling Internet as a fad and our company was slow to go online and we didn’t pursue any serious innovation. When I left in 1998, I still didn’t have e-mail or Web access from my desk. Most reporters still didn’t when I returned two years later, but I negotiated to be one of the first.

When I worked at the American Press Institute (API) from 2005 to 2008, I became heavily involved in the Newspaper Next project, focused on helping newspaper companies develop business models for the digital age. Clayton Christensen, a Harvard business professor who has studied innovation in dozens of industries, partnered with API on the project. I had seen the newspaper companies I worked for as an employee and consultant make all of the errors that Christensen said established companies typically make when faced with the threat or opportunity of disruptive innovation.

We ignored competitors because we didn’t think their product or service was good enough to worry about.

We crammed our existing model into new technology rather than imagining and exploring the possibilities.

We bogged innovation down in the culture of our hidebound organizations.

As I taught the principles of innovation in Newspaper Next, I saw newspaper companies respond with limited, narrow projects that barely, if at all, changed their cultures or their business models.

Though Buttry doesn’t know of a newspaper Web site that handles engagement announcements and weddings in the way he envisioned in his Complete Community Connection blueprint, StlToday.com, the Web site of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, uses digital tools to gather and share this news.

Connecting the Community

I began to develop my own ideas to use digital tools to do some of the jobs that were essential to connecting the community when I was cutting my teeth at the Evening Sentinel. I wrote my first drafts of a vision for a new business model. When API decided not to use my work for the second Newspaper Next report in early 2008, I started looking for a newspaper company adventurous enough to give my Complete Community Connection plan a try. At this time, I was also jumping into social media, first with Flickr and LinkedIn, then Facebook. Twitter really showed me how social media were revolutionizing how the world connected. With brief comments, questions and links, I communicate daily with thousands of people, becoming so familiar with many that when we actually “tweetup,” we greet one another like old friends.

My business model and my enthusiasm for social media appealed to the executives of Gazette Communications, and I arrived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa to start as editor last June 10th. Two days later, our nation’s worst disaster since Hurricane Katrina struck my new home. Our staff has covered the flood and its recovery with a wide range of digital tools—interactive maps and databases, social media, video, multimedia, liveblogging. We are recognized as industry pioneers in the use of liveblogging and Twitter. Our digital editor, Jason Kristufek, launched and led a series of BarCamp NewsInnovation conferences around the country.

But the disaster delayed us from the crucial work of transforming our business model. On top of the national economic slowdown and the economic challenges facing the rest of the industry, our community is reeling from a crisis that damaged or destroyed a thousand businesses. We had to join the wave of newspaper companies cutting staffs. But, unlike most of our shrinking peers, our executives faced the music the next day in a live chat.

In April, I published my vision for the new business model on my blog, calling it “A Blueprint for the Complete Community Connection.” I’m now “C3 Coach” at Gazette Communications, trying to turn the vision into fact. Bloggers and tweeps responded positively to the blueprint, and it earned me a seat at the Poynter Instit

ute’s Big Ideas Conference in July.

It’s not a digital update of the newspaper, but it is a digital update of the community connection role I first learned about as a youth in Shenandoah. Yes, the model includes professional journalists who will use digital tools to tell the community’s big news in new ways. More important, we will provide the platform where the community will tell those big stories in people’s lives that connect the community in important and meaningful ways—stories of graduation, engagement, birth and death, and who’s visiting whom and who’s in the hospital. (Many days, my biggest news now arrives from CaringBridge, a customized Web site where my brother-in-law updates friends and family around the world on my nephew’s recovery from a bone-marrow transplant.)

Just as important, C3 calls for us to move beyond the collapsing advertising and subscription revenue model. Many of those community moments described above are occasions for sending a gift or flowers. We need to enable businesses to conduct those transactions and many more through C3 using credit or debit cards. We need to connect businesses with ways to target the customers they want; when a high school graduate fills in “University of Iowa” for his college choice in our Class of 2010 site, ads for campus-area restaurants and bookstores should appear, offering opportunities for grandparents to buy gift cards.

I wish I could boast of C3 accomplishments and not just the vision. Like many others, our company has spent more time and energy on reorganization than on true innovation. I get frustrated at the pace of transforming a culture focused on producing our newspaper, television broadcasts, and news Web sites. I’m going to have to pursue this as persistently as any investigative story I ever worked, with the same commitment to reaching the goal, whatever the obstacles.

Steve Buttry is C3 coach at Gazette Communications. He can be followed at twitter.com/stevebuttry or on his blog, stevebuttry.wordpress.com.