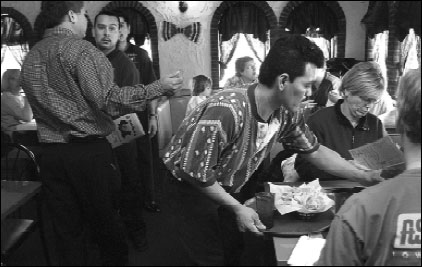

Immigrant Pablo Auelos waits on a table at the El Ranchero Mexican Restaurant in Iowa City. Photo by Scott Norris/Iowa City Press-Citizen.©

A young colleague, fired with the ideal that good journalism afflicts the comfortable, read the posting for the newsroom’s latest job: a reporter to write about homes and home decorating.

“Just what we need,” she said in disgust. “Someone to tell people how to decorate their great rooms.”

Those of us who have hung around newsrooms longer are more tolerant of sections and features aimed at middle- and upper-class readers in an affluent age. Advertising revenue pays our salaries. And we’ve fussed over window treatments and table settings ourselves on occasion.

But implicit in my young colleague’s remark is an important question: Do we slight the stories of poor citizens in our communities because we’ve become preoccupied with the high-demo reader whom advertisers crave? Does our marketing emphasis shape news values, driving us to devote any new resources to coverage of business, sports, entertainment and suburbs and to neglect coverage of hunger, homelessness, sickness and struggle? Have we become enthralled with the go-go spirit of the times and complacent in our own middle-class lives?

I know of no careful analysis of how much the media cover poverty. Even counting the terms “poor” and “poverty” would be a faulty measure. Many subjects that touch the lives of low-income Americans—foster care and welfare reform, immigration and public transit, high rents and lack of health insurance—wouldn’t necessarily show up in the tally. I can’t claim statistical proof of what our profession is documenting or neglecting.

As a journalist who covered poverty and welfare for four years and has taught college students about poverty, I can point out a lot of ingenious, committed reporting—from news features to huge projects—that brings the lives and concerns of poor people to the broader community. I can also point out missed opportunities. Despite nearly a decade of steady economic growth, 12 percent of the population lives in poverty as the federal government defines it—less than $17,000 a year for a family of four—and one-fifth of the nation lives on less than $17,500. You’d never know this if you picked up the average newspaper.

With the exception of Christmas features about needy families, few newspapers or television stations attend regularly to the lives of people living on disability checks or raising children on a hotel maid’s or nursing assistant’s wage. As journalists, we are drawn to people who are doing something—building dot-coms, merging companies. That’s where the news and the hot beats are. People living in poverty often struggle just to pay bills.

John Soloski, director of the school of journalism and mass communications at the University of Iowa, suggests a simple way to test the thesis that newspapers aren’t interested in poor citizens. Find out what parts of the market they don’t circulate in. Perhaps readers in those neighborhoods lack the income or interest in subscribing to newspapers, I suggest. Soloski counters by citing a finding by his colleague Gilbert Cranberg. The St. Petersburg Times, which is owned by the Poynter Institute and is satisfied with smaller profit margins than those that the big chains and their investors expect, has far higher penetration in that city’s poor, largely black neighborhoods than did the chain newspapers he studied—The Milwaukee Journal, Detroit News, Detroit Free Press, and The (Baltimore) Sun.

Few newspapers offer the sorts of appeals, discounts and premiums in poor neighborhoods that they offer readers elsewhere, Soloski believes. “There’s no effort made. It’s a little bit like redlining.” He then quotes Max King, formerly of The Philadelphia Inquirer, who has reported that large losses of circulation in city neighborhoods elicited no reaction from advertisers. They didn’t care. Soloski also points out that among the big newspaper chains, McClatchy is one of the few that explicitly uses circulation growth as one of the key measures used to determine executive pay. The reluctance to push for circulation in poor neighborhoods might have been present before, but Soloski believes that today’s economic pressures on newspapers drive it further.

But blaming limits of our coverage entirely on selective demographics and greedy investors is too simple. Jason DeParle of The New York Times, as high-demo a newspaper as they come, did smart, determined reporting from Washington as the Clinton administration and Congress passed welfare block grants and time limits, then reported from Wisconsin for a year after that state implemented the changes. I doubt that many Times readers clamored to know how poor families were faring in Milwaukee. DeParle and his editors decided they needed to know.

DeParle’s absence to write a book about welfare has reduced the newspaper’s level of coverage. That’s hardly surprising. Whenever an experienced and talented reporter is replaced on a beat, there’s a gap as the newcomer builds sources, knowledge and confidence. But covering poverty and welfare demands particular ingenuity and commitment from reporter and editor.

To begin with, poverty and poor people don’t have to be covered, as city hall and schools do. A newspaper can do without. Neither advertiser nor reader is likely to demand more coverage. Neighborhood activists complain about too much negative coverage of their communities, too much attention to fires, murders and drug busts. They want stories about neighborhood volunteers, high-school sports stars, bad landlords, new businesses. They’re not as likely to ask for more coverage of poverty.

Second, a poverty or social issues beat consists almost entirely of enterprise work. Few press releases will arrive on the reporter’s desk. Few press conferences will be called. The numbers that are released—food stamp use declines, welfare rolls fall—will be mere figures that must be fleshed out with patient street reporting to learn why this is happening and how people’s lives are affected. Finding affected people requires patience and ingenuity. Privacy requirements limit access to clients’ names and case files. Charities and nonprofits often must be coaxed to identify broader trends and to link reporters with affected individuals. Poor people often move around, have their phone service cut off, are reluctant to give a reporter free access to their lives. It takes time and commitment to negotiate through all that. Searching for a single mother who was trying to improve her skills and get a better job, Isabelle Wilkerson of The New York Times made her pitch in several night classes before she found a subject willing to provide the necessary access and time.

For the reporter, covering poverty often presents ethical quandaries. If the family you’re writing about needs food or transportation to the doctor, do you bring groceries and give a lift, reasoning that it’s like buying lunch for a middle-class source? Or do you restrain yourself in order to give a truer portrait of how a poor family manages? If the person being featured has her daughter’s family living illegally in her public housing apartment or lied about her job benefits in order to qualify for government-subsidized health insurance, do you include that information, knowing she could lose the apartment or the insurance? The conferences and publications sponsored by the University of Maryland’s Casey Journalism Center for Children and Families are filled with such debates.

When I was covering poverty, the political debate over welfare reform gave the story a clear focus and unquestionable importance. What would Congress and President Clinton do? How would our state respond? What would be done about such obvious barriers to work as child care, transportation and low wages?

It’s a harder story now because action is not centered in legislatures and welfare offices but dispersed within communities, workplaces and childcare centers. Welfare rolls have dropped precipitously. Many people have disappeared entirely from the public support system. What has happened to them, their children, and their neighborhoods? No report from the welfare department is going to answer that. But teachers, visiting nurses, ministers, mail carriers, cops, grandmothers, shopkeepers and families themselves might be able to.

By nature or necessity, good journalists are opportunists. Each community will present its own opportunities to delve into the lives of its have-nots. After a public health report was released about the prevalence of diabetes among Native Americans, the Minneapolis Star Tribune looked at the reasons for the growth of the disease, the terrible effects on individuals and families, and efforts to change diet and improve medical care. When Iowa’s governor declared that he wanted his state to be a magnet for immigrants to restock the labor supply, the Iowa City Press-Citizen used the chance to look at immigrants in eastern Iowa, the jobs they hold, the cultures they brought, and how they meshed with Lutherans and cornfields.

But if we believe the issues of poverty can only be treated effectively in series, we greatly constrain what’s possible. Former Nieman Curator Bill Kovach once suggested that I read Henry Mayhew, who wrote hundreds of brief newspaper portraits of the poor of London in the mid-19th century. Mayhew’s sketches of costermongers and organ grinders and flower girls are vivid and scrupulous, with copious quotes from the people themselves.

Mayhew saw his work as “the first attempt to publish the history of a people from the life of the people themselves.” He was sympathetic to his subjects and impatient with both charity and economic exploitation. But most of all, he was interested in them—curious and angry that the wealthy knew and cared so little about starvation, ignorance and depravity.

In our age of irony, exhaustion and complacency, it can be hard to get the reader’s attention to stories of the down-and-out. But there are opportunities to remind the comfortable of the struggling. When heating bills in Minnesota spiked because of a cold winter and jump in natural gas prices, Chuck Haga of the Star Tribune spent a morning at a community center where dozens of panicked people applied for heating assistance. During the Christmas season, the newspaper published brief, first-person vignettes from readers who had needed help years earlier. Their memories of the neighbor who brought a tree and presents, or a church that brought food, reminded readers living in unprecedented prosperity that fortune in America is like a Ferris wheel—it moves up and down.

Maja Beckstrom, who writes about poverty for my newspaper, went to a dental clinic for homeless men and described a roomful of men with no thought but eliminating the pain of abscess or exposed root. She also probed a related policy problem: Many of the men are covered by Medicaid, which includes dental benefits, but couldn’t find dentists to treat them because the government reimbursement rates equaled about half of the dentists’ normal fees. Moreover, if a doctor accepted the appointment and the patient didn’t show, the dentist had an empty chair and a wasted hour.

Last year, when I taught a seminar about poverty to college freshmen, I was surprised at how little they knew about the poverty of today and the past—the Great Depression, the War on Poverty. After all, their parents and grandparents lived through those times. And many Americans still live with little. Yet before my students spent time for class at soup kitchens and residential hotels, few had known anyone who is poor.

We can blame their ignorance on a dearth of history classes in high school and a lack of political attention to poverty, on economic segregation and a sense of shame that keeps even poor kids from wanting to be seen that way. But surely we can blame some of it on the way the media reflect the world back to themselves. As journalists, we need to keep reporting on lives that are alternately feared, pitied and ignored. A middle-class woman who worried about low-income apartments in her neighborhood once told me: “Poverty is like mercury. A little can ruin a neighborhood. And middle-class people know it.”

If we don’t report across that toxic divide, who will?

Lynda McDonnell, a 1980 Nieman Fellow, is political editor for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, where she reported on poverty for four years. In the November 2000 issue of The Washington Monthly, McDonnell wrote an article entitled “The Ghost of Tom Joad: What happens when an entire generation forgets what it means to be poor?”