Reporters who cover corporations might as well be covering the affairs of a medieval king sequestered behind castle walls and a moat. Corporations are not like city halls, county courthouses, or state assemblies where information is harvested freely by reporters. Efforts to scale the castle wall, even to interview the rank and file, often end in a dousing of scalding water, usually administered by the corporate executive whose job it is to keep the news media in check.

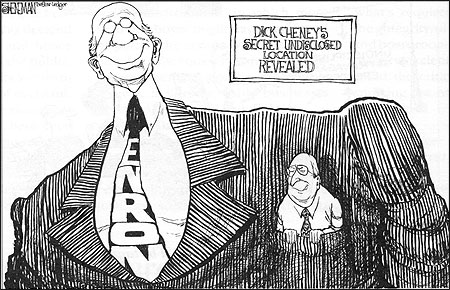

Unlike public sector reporters who benefit from public records laws, open meetings, and a robust flow of information from the bowels of government, reporters on corporate beats are accustomed to exclusion. Corporations whose stock is publicly traded disclose a large amount of information about their finances but, as in the case of Enron and too many other companies, the information is written to obfuscate, not enlighten. (And these reports are prepared primarily for stockholders—the corporation’s owners.) Publicly held corporations also conduct once-a-year meetings—again, primarily for shareholders—that seldom offer truly candid assessments of a company’s financial condition and prospects. In many instances, corporations hastily rubber stamp the routine business on the agenda, then dance around the inquiries of shareholders who dare to challenge company policies or suggest changes in corporate governance. Some corporations actually go as far as to conduct these meetings in places such as Wyoming and North Dakota to discourage attendance, as the bygone SafeCard Services did in the 1980’s.

So it came as no surprise when I read about the heavy-handed response by Enron to early inquiries about its finances by reporters Jonathan Weil of The Wall Street Journal and Bethany McLean of Fortune. Weil had to run a gauntlet of seven Enron officials before writing a September 2000 article that rankled Enron. (His experience reminded me of a 1978 assignment when an electric utility dispatched a battery of four executives to hear my questions about a controversial power project that threatened a town’s mountaintop water reservoir. When one executive groped for an answer, another would chime in, and when the rapid-fire, two-hour interview was done, I wasn’t entirely sure who had said what in my notes.) McLean’s questioning months later ruffled Enron’s feathers even more. Jeffrey Skilling, Enron’s former CEO, called her questions “unethical” before hanging up on her. Enron nonetheless sent its damage-control squad to New York to meet with her. Expecting the worst, Enron founder and Chairman Kenneth Lay called one of McLean’s editors in a fruitless attempt to spike the story.

Preemptive strikes by corporations whose dubious business or accounting practices are about to be exposed are merely another hurdle for corporate watchdogs in the news media. It doesn’t stop there. Competent business reporters are regularly blackballed for writing critical stories or for failing to trumpet a corporation’s business ventures.

Quarterly earnings reports can be a minefield in this regard. Decades ago, when the bottom line meant just that, net income (or loss) was the ultimate measure of a corporation’s performance. But in today’s environment of permissive accounting rules and forgiving investment analysts, reporters are criticized for not giving corporations enough credit for so-called “one-time” charges against earnings. Events and items such as plant closings, severance payments to laid-off employees, business writeoffs, and even unsold products are singled out in corporate earnings reports as “extraordinary” or “non-operating” expenses. Corporations, eager to present the most favorable picture possible to potential buyers of their stock, prefer investors to look at the profit line shorn of the “one-timers.” The idea behind all of this is to expunge past blunders and steer investors to the future, which somehow always manages to be bright. Never mind that the corporation has squandered millions or billions of dollars.

If reporters ever think they’re going overboard with their skepticism of reported earnings, they should take a closer look at the Securities and Exchange Commission’s book-cooking cases and investigations involving Xerox, Waste Management, MCI Worldcom, Qwest Communications, Adelphia Communications, Computer Associates, Enterasys Networks, Network Associates, RSA Security, Analytical Surveys, Sunbeam, W.R. Grace and, well, you get the picture.

Pity the reporter who chooses not to toe the corporate line. Corporations stung by even modestly critical stories have denied reporters access to CEO’s, denied entry to annual meetings, and leaked stories to competitors as punishment. I recall one Fortune 500 CEO a few years ago who responded to a skepticism-filled South Florida Sun-Sentinel article on his company by buying a full-page ad in the same newspaper excoriating the two authors. The paper then published an op-ed column by the CEO in which he described how journalism had become “infotainment.” This same CEO complained to my editor (I was at The Miami Herald at the time) after I had written that his company’s superstores were considered by industry veterans to be money-losing white elephants. My editor stood behind me, although with some trepidation, because the company was our biggest advertiser. A year later, the CEO was replaced. One of his successor’s first acts was to pull the plug on the superstores.

Persuading editors to put the reins on their reporters appears to be part of the corporate media-management manual. In many instances, it’s justifiable because many reporters who cover corporations are “shake-and-bake” business reporters transferred from the city desk without receiving any education on corporate finance or capitalism in general. In a definitive Freedom Forum report on media-corporate relations entitled “The Headline vs. The Bottom Line,” 70 percent of CEO’s polled said journalists don’t have the sufficient background to cover business. Forty-five percent of reporters agreed.

Still, it isn’t only rookie reporters who are mistreated. Corporations try their best to eliminate proficient business reporters who become too nosy. Consider these examples:

- In the early 1990’s, former Seattle Times reporter Byron Acohido dogged Boeing Co. with articles spotlighting rudder failures on the Boeing 737 jetliner. Boeing didn’t like it and pressed Acohido’s editors to reassign him. The Times refused. Later, the National Transportation Safety Board recommended that Boeing alter its 737 rudder system. Acohido went on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1997 for his coverage of Boeing and aviation safety.

- In February 2000, after KHOU-TV in Houston broke the story linking certain Firestone tires to an unusually high number of blowout related traffic fatalities involving Ford Explorers, Bridgestone/Firestone fired off a long, testy letter not only to the station’s general manager, but to the CEO of the company that owns it, Belo Corp. The tire maker accused reporter Anna Werner of having been “co-opted” by personal injury lawyers suing Bridgestone/Firestone. It called Werner’s assertions untrue. Yet, by the end of 2000, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration connected 148 fatalities and 525 injuries to Firestone blowouts on Ford Explorers. Firestone recalled 6.5 million tires.

- In February 1997, two reporters for WTVT-TV in Tampa, Florida—Jane Akre and Steve Wilson—completed a segment on the sale of milk drawn from cows injected with the FDA-approved bovine growth hormone (BGH), the safety of which was questioned by scientists and grocery chains. The day before the story was to air, the manufacturer of BGH, Monsanto Corp., wrote a letter to the station saying it expected a hatchet job. It asked that its side be told in greater detail. Akre and Wilson objected to the insertion of what they considered propaganda, but the station sided with Monsanto. The reporters threatened to report the matter to the Federal Communications Commission and were fired for insubordination. They sued the station, and Akre was awarded $425,000 in a jury trial. Their story never aired.

- This January, New York Post reporter Nikki Finke wrote two stories about a lawsuit accusing Walt Disney Co. of cheating another company out of millions of dollars in royalties from the sale of Winnie the Pooh merchandise. Disney wrote a letter to the Post alleging “serious factual errors” in the story, a claim that Finke denied. Although Finke says editors never shared Disney’s qualms with her—and no corrections ever ran—the Post fired Finke on February 19. The Village Voice reported that Finke’s dismissal followed a tirade by Disney CEO Michael Eisner to Post owner and fellow media mogul Rupert Murdoch. In April, Finke sued the Post, Disney and Disney’s chief spokesman for $10 million.

These are the lengths to which some corporations will go to exert control over news coverage. At the other end of the spectrum, there are corporations that take their coverage in stride and, in fact, welcome news inquiries and help reporters understand esoteric issues. Former Ryder System CEO Tony Burns took me into his confidence on several occasions before his inability to sate Wall Street ultimately led to his early retirement. And Martin Hanaka, the CEO of The Sports Authority, never ducked a phone call or hid behind a flack, even when his company was hemorrhaging and closing stores.

Enron, however, took the field of media relations to new heights. Enron didn’t settle for the usual currying of reporters’ favor with free meals and product giveaways, but paid tens of thousands of dollars to selected media pundits such as Bill Kristol of The Weekly Standard, Lawrence Kudlow of CNBC, Peggy Noonan, contributing editor of The Wall Street Journal and Time, and Irwin Stelzer of The Weekly Standard and The Sunday Times of London for consulting and service on advisory boards as Enron pushed for favorable federal energy policies. (Enron also hired Paul Krugman, then a Princeton economics professor and author, who had not yet joined The New York Times as a columnist, but had been writing for Fortune and Slate.) It’s no stunner to hear about corporations passing big checks to working journalists. The journalists should have known better.

Looking ahead, I would like to believe that the federal forays into corporate accounting mumbo-jumbo and whatever comes out of the Enron-Arthur Andersen mess will make business ethics fashionable and persuade corporations to be more forthcoming, if not to embrace, media coverage. Disclosure requirements will help investors, and I suspect auditing firms will start looking a lot more closely at their clients’ ledgers. Then again, 20 years of covering corporations tells me not to expect to find it easy going as I try to get inside the castle gates.

James McNair has been a business writer with The Cincinnati Enquirer since July 2001. Before that, he covered the business beat in South Florida for 17 years, including for The Miami Herald, where during the past 12 years he reported on corporations and on white-collar crime.