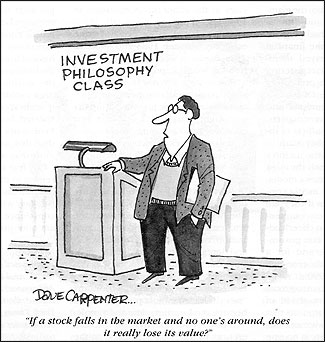

Cartoon by Dave Carpenter. Previously printed in the May 2002 Harvard Business Review.

“I don’t get it.”

Those four humbling words became the key to unlocking the secrets Enron Corporation had stored up before its collapse last December. But those four words proved to be a hard admission for most analysts who were paid to know what Enron was up to. Hard, too, for Enron’s highly compensated outside directors charged with protecting shareholders’ interests.

Nor is this a statement that reporters and editors like to make either in public view or to each other. Journalists take pride in finding out answers to questions, not in being stumped and misled. What readers and viewers want from us is a way to see the bottom line with clarity and not confusing, unfinished calculations.

Fortune’s Bethany McLean, the first journalist for a major business publication to question Enron’s inflated reputation, started down this path toward clarity when in March of 2001 she spotlighted a central issue about Enron that neither she nor much of Wall Street could explain. “Start with a pretty straightforward question,” McLean wrote: “How exactly does Enron make its money?”

Last spring, as Enron’s high-flying stock descended, other reporters raised questions and quoted skeptics. In a probing U.S. News & World Report story in June, Anne Kates Smith asked whether Enron was overpriced. She quoted Houston securities analyst John Olson, an Enron doubter: “They’re not very forthcoming about how they make their money. I don’t know an analyst worth his salt who can seriously analyze Enron,” Olson said. But it was not until mid-October, after Enron’s carefully hedged admissions of several unexpected and ill-explained financial setbacks, that the mainstream press began to take notice. Then Enron’s abstract accounting story took on a human face, that of its chief financial officer Andrew Fastow, an operator of mysterious investment partnerships that were lining his pockets. An article last August by Wall Street Journal reporters Rebecca Smith and John Emshwiller put a spotlight on Fastow. By October, other reporters were digging and more devastating disclosures followed. In December, Enron folded, with the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. history. By then, something like $60 billion in stock market wealth had disappeared in just a year.

It is quite an understatement to say that the press was late in getting to the scene of this fire. In a Business 2.0 column, Erick Schonfeld acknowledges having made Enron’s chief executive Jeffrey Skilling its cover boy for the August/September 2001 issue, a week before he resigned. But with this fire, there were reasons why journalists weren’t able to supply clear answers, and the primary one is that the answers were hidden, out of reach. “Mea cul-pas aside, Enron’s collapse caught analysts and journalists off guard because there was little hint of trouble in the company’s reported financial statements,” Schonfeld wrote.

That’s true. Enron took great pains to conceal what it was doing and create illusions of success in the quarterly and annual securities re ports it issued. How much money Enron really brought in and how much of its revenue and profit were accounting fictions is still not clear. On some critical questions about its business ventures and partnerships, Enron executives simply lied.

Hints and clues were there, however. Some trade press reporters, who closely watched Enron’s operations, saw them. “The numbers just didn’t add up,” says Barbara Shook, a reporter with Energy Intelligence Group, who questioned Enron’s claims of success a few years ago. Jim Foster of Platts energy publications is another observer who smelled something funny about Enron long before the rest of us figured it out. But even these doubters did not effectively challenge the sway of Enron’s mystique. “Many of us didn’t question them as closely as we should have,” Shook says.

Challenging Enron was no picnic. The core of its business was based on accounting strategies built by academic and financial experts operating on the outer limits of accepted accounting practices and, it turns out, often outside the lines. It was a world of “shared-settled puts,” “reverse contingent forwards,” “synthetic equity,” and “trapped appreciation.” If you didn’t understand, Enron suggested, well maybe you were just short a few cards in your deck.

Llewellyn W. King, founder and publisher of a group of energy, defense and other trade publications, and as canny as they come, had Enron’s Skilling as a keynote speaker at an energy conference several years ago, when technology stocks were still surging. King listened as Skilling described Enron as a new hybrid company that would earn dot-com stock prices by taking its energy trading expertise into widely disparate fields, creating new commodity markets for Internet transmission, water supply, advertising space, and other services. “It sounds wonderful,” said King, “but I don’t see it.” King recalls that Skilling replied good-naturedly, “I guess that’s right.”

In this case, Skilling was plying his charm. Other times, questioners and skeptics were sharply confronted, as Fortune’s McLean discovered when

Skilling sent Fastow to New York on a corporate jet to challenge her reporting. After U.S. News & World Report quoted securities analyst Olson’s doubts about Enron’s stock market value, there came a blistering note to Olson’s boss from Enron chairman Kenneth Lay.

If the public record about Enron was hard to trace, so were the inside tips that reporters began getting about Enron’s partnerships. I received a tip in November from a person describing a partnership named Chewco that The Wall Street Journal had uncovered the month before. This caller said Chewco had produced huge, concealed profits for former Enron executive Michael Kopper and his friend and explained the outlines of a byzantine off-balance-sheet structure. My questions weren’t very sharp, and the tipster was nervous. After two brief conversations, the calls ceased. It took weeks and some good luck to pin down printable details about the Chewco windfall.

Today, many journalists have become Enron specialists. A year ago, there were few. As an energy reporter, my interest in Enron used to be limited to its role in trading electricity and natural gas during California’s power crisis, a story that remains to be told.

In hindsight, it is clear where reporters should have been looking. Enron’s feet of clay were uncovered a year ago by operators of hedge funds and investors looking for overpriced stocks to bet against. A report in May 2001 by Off Wall Street, a private research firm, laid out fundamental weaknesses in Enron’s financial position and in the new ventures it was counting on to keep its stock price up. While Enron’s revenue was soaring from mid-2000 to 2001, the profit it was making on each trade was shrinking, the report noted. And Enron’s operations were producing a strangely small amount of cash. The publication, which goes only to private clients, recommended that investors dump Enron stock. Another hedge fund operator with doubts about Enron went looking more than a year ago for firsthand information. He got names of former Enron employees from Internet job sites and called them at home,

getting enough information to confirm his doubts. This became the same technique reporters on the Enron story began using six months later.

Behind the war stories are some old maxims for business reporters and editors:

- We need to question success stories that seem too good to be true.

- We need to listen to contraries and skeptics and also to short-sellers, recognizing the sharp axe they grind.

- Regardless of their size, news staffs can make choices and set priorities for investing in in-depth coverage on companies and business trends that matter most.

- We need to push harder for answers and hold companies to a more demanding standard of disclosure. If they don’t have answers, we need more stories that say so.

Enron reveled in its annual designation as one of the nation’s “most innovative” companies. In many ways, Enron was an innovator, but the press needs fewer pop designations like that one and better reporting on what the innovations are and whether they are working. And we need to produce fewer lists of “The Ten Most Innovative Companies” or “The Ten Toughest CEO’s” and “Who’s Who in Risk Management” or “The 100 Best Companies to Work For.” We would serve readers and investors better with lists like: “Ten Incomprehensible Financial Reports” or “A Dozen Companies That Won’t Say How They Make Their Money.”

When vital information isn’t disclosed, journalists need to say, “I don’t get it.” And do so in print and on the air. That’s a starting point toward getting better answers.

Peter Behr, a 1976 Nieman Fellow, covers energy issues for The Washington Post and has reported exclusively on Enron since October.