Cartoon by ©John Deering/Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

As I write this, the NASDAQ Composite Index is trading around 1800, more than 75 percent below its high of two years ago. Shares of Cisco Systems are trading at $14, General Electric is at $31, and AOL Time Warner is under $18—all fractions of their former highs. Did America’s business media present a fair warning back in 1999 and early 2000 of the debacle in high technology and other stocks that was to come? No one could reasonably argue that they did.

There were occasional doubters, of course. But they were in the minority. Rather than inform, the reporting by these dissenters seemed to provide the disclaimers necessary to enable the rest of the news media to wax enthusiastically about the miracles of information technology and America’s prosperity, often called “unprecedented,” without justification. Each time I heard this, I winced. In the 1960’s, unemployment was lower. During the 1920’s, and again in the 1960’s, both Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and productivity grew faster. Throughout most of the 20th century, one worker could support a family. Not now. And now a far higher proportion of the family budget had to be devoted to education and health care, whose prices rose far faster than typical family incomes. Income gaps were widening and child poverty was high. An ever greater proportion of Americans had no health insurance. The quality of public education was tragically unequal. And what supported high levels of consumption were high levels of personal debt. Though important gains had been made, this was not America’s finest economic hour.

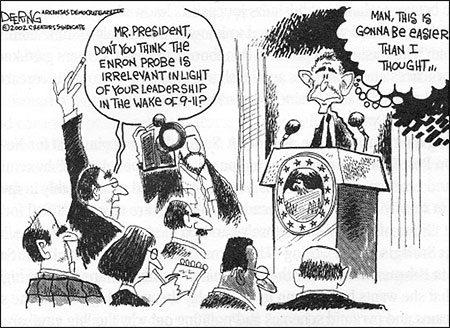

Not until the accounting scandal surrounding Enron surfaced did some in the news media at least acknowledge their negligence. And Enron’s situation was not uncovered by the press, by Wall Street, or by Washington. Enron was “caught,” not because Wall Street recognized its specific deceit, but because other high technology stocks collapsed. The fall in prices was contagious, and Enron’s stock also began to fall, if modestly, as a result. But because Enron used its stock to guarantee its own financing in a complex maze of partnerships, as the stock price fell, its partnerships became unglued. They had to report big losses. Had the market gone back up and the slide in its stock price been stopped, Enron would still be telling its story—and what a whopper! Like children around a campfire, the news media eagerly absorbed Enron’s tall stories wide-eyed and ready to repeat, even exaggerate further, what they had been told.

Enron was merely the manifestation of a broad failure on the part of the financial media. Is this language too tough on the financial media? To the contrary, if anything, it is too weak. The financial media in the 1990’s were like fatted calves, and Wall Street analysts and corporate public relations teams pounced almost at will. I was on an evening talk show with a respected Washington journalist and a financial cable network host. The Washington editor claimed Enron was a “green eyeshade scandal.” In other words, it was too complex to expect journalists to crack it. The television reporter said there was not much of an audience for critical stories when the market was high, even though his network tried to do them occasionally. With those disclaimers, these reporters exonerated themselves.

The Enron transactions were complex, but the financial media did not simply miss the Enron scandal. They extolled the virtues of the company in ways rarely seen before. Fortune named Enron the most innovative company six years in a row. It listed it as one of the 10 largest companies in the nation, even though Enron reported as sales the value of the underlying securities in their derivatives transactions, thus inflating its actual size by several times. (Financial companies report only the commissions or spreads as sales revenue.) Almost every major publication joined in undiluted praise, several putting Enron on the cover repeatedly. The proof that this decision was right: The stock price kept rising.

Enron simply told perhaps the best story of the decade—in a decade of tall tales. With its business strategies, Enron touched all the big media buttons: globalization, the new economy, derivatives trading, deregulation and the Internet. Enron’s story was consistent with the biggest economic story, which was the much reported belief that America was in the throes of a “new economy” and that high technology would remake the economy, with information as its main asset.

In time, television and financial magazines, in particular (newspapers were somewhat more responsible), became part of Enron’s sales process, while increasing their own. Readers and viewers reveled in hearing of one miraculous business success after another. After all, these news media outlets attracted advertising from the glamorous industries as well, and did not want to be the bearers of bad news. At the same time, many in the financial media increasingly portrayed themselves as business experts, registering firm opinions rather than presenting several sides of an issue. Of course, they cited Wall Street analysts and economists as if they also were experts, mostly ignoring patent conflicts of interest in most assertions they made.

Even if this scandal got the nation’s attention, there has been only the most passing mea culpa in the news media. Members of the financial media continue to quote analysts as if they are objective sources. Television commentators, in particular, remain cheerleaders for the market, for certain government economic policies, and for a variety of myths about why the economy grew rapidly in the late 1990’s.

This lack of self-criticism among most journalists amounts to an abuse of power. It is the work of journalists that often calls public and private entities to task, but apparently there is no one and nothing to call the media to task. Largely, that is good news; it ensures our free press. But it reminds us of the special responsibility journalists have to monitor themselves. Some editors expressed dismay at their news organizations’ reporting of Enron. But I’ve heard little about how they might seriously mend their ways.

The financial media reported well on neither the Enron story nor the economic stories impacting the American people in the 1990’s. Among journalists there seemed little sense that they served as a public watchdog during this time. There’s been no golden age in financial journalism, but in earlier times there did seem to be some sense of proportion. But during this past decade, proportion wasn’t what got reporters far with many editors of the financial news.

The evolution of the term “new economy” suggests how this single enthusiastic idea affected reporting. Business Week was the leading advocate of a new economy. It first used the term in 1981 when it had largely to do with the emerging dominance of services in the economy. A recession in 1982 ended new economy talk, but it was resuscitated during a revival of the economy between 1983 and 1985. In 1986, Business Week, Fortune and U.S. News & World Report each published a “new economy” cover story. Then the stock market crash happened in 1987, and slow economic growth during the next eight years ended talk of a new economy reinvigorating America.

Business Week rediscovered the new economy in 1995, this time basing its emergence on globalization and high technology. In time, nearly everyone in the news business climbed aboard, defining it in all different ways. In 1997, The Washington Post celebrated the kitchen sink approach, putting globalization, new technology, restructuring and deregulation into its definition. At Business Week, the definition was also evolving. Now it was risk-taking venture capitalists that made the economy “new.” Then, for most publications, it became the Internet, pure and simple.

A Lexis-Nexis search reveals 325 references to the “new economy” in the print business press in 1995. Just four years later, in 1999, there were 3,215 such references. By 2000, the number had risen to 22,850. A single phrase thus ruled financial journalism, but what the phrase really represented was a poorly defined idea that could be anything an editor wanted it to be. As long as the stock market kept rising, there was little reason to question it. (The only financial magazine I found that criticized the term consistently was the generally conservative Economist.) Meanwhile, high-technology advertising soared in the business pages and, no doubt, on television as well.

Enron’s story fit neatly into this world of exaggeration. Americans wanted a “new economy” and could be excused for thinking they had one based on what they read and heard. In reality, they had suffered more than 20 years of slow growth and stagnating wages since 1973 and needed an explanation for the economic boom of the 1990’s. The new economy was it, and the business media thrived while promoting it.

As a consequence of hyping a hope and ignoring a reality, Enron probably got away with fabricating much of its earnings between 1995 and 2000 and hiding enormous amounts of debt. Its executives became wildly rich on the basis of little more than a good rap that the business press wanted to hear. Still, the mythmaking continues. America grew rapidly in the late 1990’s because it embraced markets, wrote one respected business journalist recently. Economics is so much more complex than that, and its forces affect so much more than what happens on Wall Street.

My fear is that the only impetus for reform in the business media—so that balance and complexity and solid reporting will prevail—is journalistic conscience. Given that assumption, I am not optimistic.

Jeffrey Madrick is the editor of the economics affairs journal, Challenge, and author of “The End of Affluence,” among other books. He is a contributing columnist to The New York Times and was formerly an economics reporter and commentator with NBC News and financial editor of Business Week.