Only outside of the continent might people think of Europe as being a fully integrated political and sociological entity. From within, there is a great diversity of thought among the 15 members of the European Union. Divergent views about the scientific issue of cloning offer a perfect example of this disparity. Reporters who cover the issue remain largely prudent since cloning is still an unfolding issue about which there are and will be many different perspectives. But, at times, there are sensational clone-related events that lead to an eruption of more debate.

In Germany, the ruins of fascism and World War II still infiltrate most cultural subjects. In the realm of biotechnology, Germany was among the first western European countries to pass a law forbidding embryo manipulation. Most striking was the publication in 1999 of a book, “Rules for The Human Zoo,” written by liberal philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. Many perceived it as a justification of eugenics, whereas Sloterdijk believed he was inviting readers to reflect on new challenges offered by the rapid progress in science.

Starting with a story in the German weekly Die Zeit, a long, complicated debate was engaged. It involved many thinkers and philosophers and resulted in much confusion for everybody, including the participants. Journalists from a number of German and foreign newpapers tried to report accurately on the numerous and evolving points of view, but the debate was blurred because Sloterdijk’s text was understood as a justification of eugenics and Nazism. This prominent philosopher argued against these accusations, presenting himself as a left-wing thinker. But the emotions connected with these accusations hindered for a long time any subsequent assessment of his ideas.

In France, history also twists the debate. Many intellectuals want to address cloning while considering policies involving universal human rights. They establish themselves as abstract consciousness for the human being—an echo of the French revolution. The various scientists who have led the national ethics committee, like Axel Kahn, frequently addressed the press on the issue of cloning. (Revision of the bioethics law was due in 1998 but is still delayed.) But if this debate is regularly portrayed in the newspapers, it has not yet found its place on the political agenda since it seems that politicians are afraid to take a position on such a sensitive issue. Only a few days after former French Prime Minister Lionel Jospin said he would authorize therapeutic cloning, he withdrew his decision. In the recent presidential campaign, French leaders did not address the cloning issue.

In contrast to theoretical debates in France and Germany, cloning has been considered as an issue of practical concern in Italy. There, citizens wanted to know more about the possibility of giving birth at an older age and about specific benefits they might receive from the current progress of scientific research and new opportunities offered through genetic engeneering. Until July 2001, Italy had some of the most tolerant laws regarding the use of fertility science in Europe. A post-menopausal woman could receive implants as a method of giving birth.

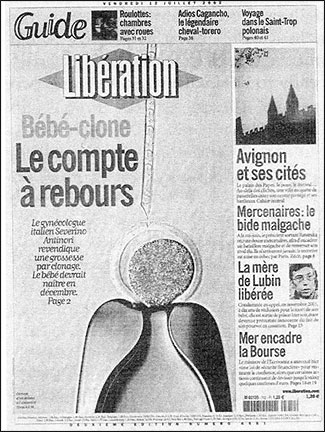

In Italy, however, one name became emblematic of this scientific contro-versy—as Sloterdijk did in Germany. That name is Severino Antinori, a professor of medicine at the University of Rome. In August 2001, Antinori was the first to publicly announce the launching of diverse human cloning programs. Accompanied by slogans such as “reproductive cloning is a form of therapy,” his comments provoked many emotional reactions, as he had obviously hoped they would.

While covering such news, journalists inform readers of the general trend against reproductive cloning, and they often react negatively to Antinori’s flamboyant speeches. But their informative approach was stained for many citizens by how others in the media turned this story into sensationalized and “scoopy” coverage. It should be said that Antinori provokes and manipulates the media with some talent. Recently, he announced the planned birth of the first baby clone in December of this year. Strong words such as “worrisome” or “horrific” are often used in headlines, but most papers, such as Le Monde in France, keep a neutral voice. However, such neutrality is likely to disappear as the situation unfolds.

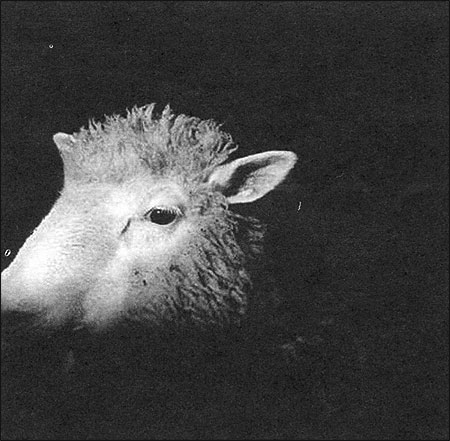

British press coverage of cloning offers a third way to reflect about the issue. Great Britain has the Union’s most permissive legislation about embryo research. Few people remember the first test-tube baby, created in Britain in 1978. Many more recall the cute genetically conceived sheep, Dolly, who appeared on the front page of many newspapers swhen her existence was announced in July 1997. The British Parliament formally approved therapeutic cloning in 2001. In such a context, the British press usually adopts a questioning, wait-and-see tone. Specialists are warmly invited to feed the ongoing debate in the opinion pages.

In 1998, a referendum was held in Switzerland in an attempt to forbid any kind of new research on genes. It was defeated, but only by a small margin. This probably reflects the strength of advocacy that came from the academic research community and those involved in the field of genetic research. Their views were largely relayed by the press whose coverage during the referendum debate became intense and reached a very large audience.

What kind of larger assesment can be drawn from this wide diversity in the European press? In their editorial positions, most newspapers (at least non-religious ones) unanimously reject reproductive human cloning, but they don’t take sides about therapeutic cloning or use of stem cells. (Reproductive cloning aims at the perfect reproduction of a human being, whereas therapeutic cloning reproduces some cells only, in order to cure diseases.)

In Europe, where the press is very often politically oriented, the traditional clash between liberals and conservatives (left vs. right) is not well reflected in the field of bioethics. European “Green” parties, for example, have been campaigning for a long time against genetic manipulation, as they warn people against the dangers of the biotechnology. But their positions are not well represented in large-circulation newspapers.

Cloning is a new topic for political debate, and the complicated and ever-changing scientific knowledge blurs positions. Confusion is perhaps the most apparent common ground among politicians and reporters. Individual journalists who write for the same magazine might have very different positions about this issue.

Many European journalists would certainly like to stimulate a vigorous debate about cloning. Until now, they have been very careful about not expressing their own views. Instead, they invite scientists, politicians and philosophers to present their opinions. If a referendum about cloning—such as the one in Switzerland—were to be organized in Europe, it would certainly invite the press to become more partisan in how they portray this issue. Considering the diversity of national cultures, religions and history, it is unlikely that any universal point of view about cloning will emerge in the European Union anytime soon.

Olivier Blond covers science for Courrier International, a weekly French magazine that publishes selected translations from the world’s major newspapers.