Tension between scientific research and public policy is natural and even desirable. The conflicts enveloping policymaking about stem cell research have resulted, however, in a Gordian knot of red tape. A consequence: reduced support for cutting-edge research and hobbled prospects for the growth of biotechnology in the United States. Dimensions of this costly and counterproductive maze became clearer to me last October when a senior policy adviser at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guided me and other journalists attending a stem cell research seminar through regulations that governed scientists who received federal funding.

As an editorial writer at the San Jose Mercury News focused on writing about medical and health issues, I was aware that in August 2001 President Bush had placed significant barriers in the path of such research by limiting it to already existing lines of stem cells. Before attending this seminar, however, I hadn’t realized to what extent he had, in just a few words, created the need for such a massive structure of rules, documents, timelines, supplements and accounting procedures.

Illuminating Policy Debates

Therein lies, of course, one of the main reasons for attending such a seminar. While science writers have the job of explaining science, my job is to delve into the political decisions that affect what scientists get to do with our tax dollars. Behind the whiz-bang stories of far-reaching discoveries and cosmic breakthroughs are the little-noticed policy debates that shape the future of research in this country. The ways in which politics is allowed to trump science in this country is something that seldom makes the “science and technology” sections, but that I believe readers ought to know. In-depth seminars provide time to delve into these issues. And in the dim recesses of this NIH meeting room, I began to imagine this intertwined mass of requirements growing like an enormous tumor and impeding serious research far into the future. How much better it would be if, like Alexander in Anatolia, someone could seize a sword and slash through the knot.

Earlier in this seminar, sponsored by the Knight Center for Specialized Journalism, Washington Post science writer Rick Weiss had referred to stem cell research as a form of guaranteed employment for journalists. But Bush’s directive to the NIH, I concluded, had created a similar guaranteed employment program for a certain breed of federal workers. They’d spend months writing regulations intended to prevent scientists from using a penny of federal funds for examining cells from lines other than those on the NIH human embryonic stem cell registry. They’d provide unique codes for each cell line, assuring that each cell existed before 9 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time on August 9, 2001. They would also devote some of their energies to “parsing facilities and administrative costs for eligible research from ineligible research,” in the words of this senior policy adviser, all the while believing they were advancing the cause of science.

Since that seminar, issues involving stem cell research and its new cousin, “therapeutic cloning,” have become, if anything, even murkier. Much of the political resistance to such research is based on religious beliefs against the idea of manipulating human life, which supposedly begins at the moment of conception. But is that the moment? Or is it the moment of implantation? Or of cell differentiation? There are differing views that shape different answers to these and other questions. As someone who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area—and tries to reflect and inform public opinion—I am attuned, perhaps more than most Americans, to the wide variety of views on humanity, the individual, and community held by Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and others. In our readership, the portion of residents who agree with President Bush on this issue is small.

President Bush might have thought he had forged an ideal compromise between science and religion when he announced his policy. But this compromise turned out to be more like what King Solomon suggested to the two women squabbling about an infant: Cut the baby in half and each gets an equal part. In this case, the metaphorical sword is more like Solomon’s than Alexander’s.

This seminar provided many “aha” moments similar to these and, since I’ve returned to my job, I’ve struggled to keep up with—and explain to readers—implications of the most current research, policy initiatives, and international competition in biotechnology. For someone who majored in English, as I did, simply keeping up with scientific news about stem cell research and cloning has proved challenging. When I took biology courses in high school and college, mitochondria’s role was steeped in mystery, and the first heart transplant had just occurred. Genetic causes of many diseases weren’t even suspected, much less explored. Now, to write editorials, I am trying to understand how cells from a blastocyst could be coaxed into producing insulin and how a nucleus could be teased out of one cell and introduced into a human egg, creating potential life—without conception.

Because I am a journalist from California, at this seminar I fielded many questions from colleagues on my state’s encouragement of stem cell research. Weeks earlier, I’d written an editorial applauding California’s forward-looking legislature and governor for approving a bill endorsing research on stem cells and allowing so-called therapeutic cloning, which many proponents prefer to call somatic cell nuclear transfer. (California, along with nearly everyone except the Raelian cultists, opposes reproductive cloning of humans.) Another Californian, Senator Dianne Feinstein, is a leader among those calling for federal legislation allowing research involving stem cells and nuclear transfer, while banning reproductive cloning. I explained to the other journalists that California’s move was purely symbolic—a point I had made in my editorial, since future federal legislation would trump state law and the lack of federal funding would cripple research that called for creation of new stem lines.

I was wrong to portray California’s policy as being so modest. Symbolism turned out to be stronger than I thought it was. Since September 2002, several states have followed California’s lead. Of course, several other states have gone the opposite direction by banning all cloning. In the states calling for the freedom to pursue research, the proponents have made it clear that congressional action to ban stem cell research—as called for in a bill that twice passed the House but not the Senate—wouldn’t reflect the opinion of most Americans.

As for the crippling effect of Bush’s decision, I was a bit off the mark there, too. What I had not considered strongly enough was the possibility that private funders would step in to finance such research. Several weeks after the seminar, Stanford University announced an anonymous grant of $12 million in private seed money that would help to establish a new Institute for Cancer/Stem Cell Biology and Medicine. And high-tech leader Andy Grove pledged five million dollars to help launch a new embryonic stem cell program at the University of California-San Francisco. Those amounts are far less than the billions of dollars that are available to the NIH. But, along with private firms such as Geron, they will help to keep Northern California in the forefront of research. And they give researchers even more ability and reason to resist federal restrictions.

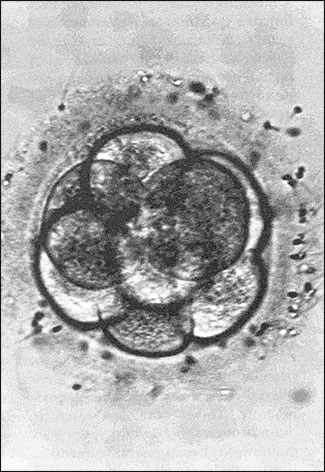

An eight-cell embryo is shown three days after insemination. Photo by Eastern Virginia Medical School/The Associated Press.

Getting Past the Media Hype

The history of stem cell research is short. The future could hold tremendous promise. Or stem cells could become the biological equivalent of cold fusion. So far, the media hype about them has far outrun their reality in terms of current applications. What has been most prominent to most readers, listeners and viewers in these debates about stem cells and cloning is the turmoil of false hopes and celebrity exploitation, as famous people like Michael J. Fox and Christopher Reeve arrive on Capitol Hill to testify. Religious ferment combined with the anti-intellectualist furor and political manipulation have also served to obscure what’s really happening in the lab.

In trying to inform public debate about these issues, it doesn’t help that so few people who aren’t scientists or doctors understand the complex science involved or even know the difference between embryonic stem cells and cloned cells. On the other hand, many of the Mercury News’s readers understand the science perfectly well because they are the scientists and technicians who are doing it. Luckily, my editorials focus on policy and funding decisions—and while those decisions may be obscure, they reflect human nature, which anyone can understand. Struggling to explain the science, the policy issues, and the ethical concerns is, indeed, as Rick Weiss reminded us, a sort of guaranteed employment for journalists.

Barbara Egbert is an editorial writer at the San Jose Mercury News. A graduate of San Francisco State University, she has also worked for the Nevada Appeal (in Carson City), Reno Gazette-Journal, and Alameda (Calif.) Newspaper Group. Her interest in health care and medicine was sparked by a year working as a volunteer at People’s Community Health Center in Baltimore, Maryland.