Mainstream media coverage of stem cells and cloning is starry-eyed, lopsided and deceptive. But at least it is no worse than journalists’ coverage of the dot-com bubble.

As the Internet bubble inflated, reporters magnified the industry’s promises and predictions. They rarely investigated the overlapping networks of venture capitalists, insider stock deals, the hype, backscratching and the Ponzi-like financing of Internet companies whose sole assets consisted of fawning press clips and a foosball table. Of course, after the bubble burst and a few trillion dollars worth of hopes and illusions escaped into the ether, many journalists have judiciously written acres of cautionary stories and investigative pieces.

This pattern has repeated itself in biotech, only we’re still somewhere between boom and bust. Remember those breathless pieces on television, in Time and Newsweek and many other publications, about the miracle new cures that will come from cloned embryos’ stem cells—cures for Parkinson’sAlzheimersDiabetes so desperately sought by dying people? Hasn’t happened. Won’t happen, or not for many years, and not until today’s patients are dead and gone, scientists now say, sotto voce.

But the press furor created a mini-boom for the few scientists and companies that specialize in this arcane corner of biotech and for the reporters who cover it.

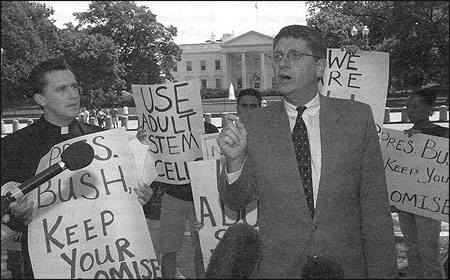

Antiabortion activist Randall Terry talks about his opposition to stem cell research during a demonstration in Lafayette Park across from the White House in August 2001. The demonstrators were asking President Bush to ban embryonic stem cell research. Photo by Stephen J. Boitano/The Associated Press.

Language Drives a Story

I’ll start with the language. Stem cells from embryos are typically called “embryonic stem cells,” but there’s nothing embryonic about them. They are fully formed and fully prepared to multiply into a living, breathing person. Better that they be called “embryo stem cells” or “embryos’ stem cells.”

This terminological transmutation is important because it changes readers’ perceptions of the issues involved. This change becomes clearer in the intertwined debate about human cloning, in which some scientists want to create new stem cells by cloning embryos from adults with interesting genetic features or diseases. Until 2001, this process was routinely described as cloning. But once the technology matured to the point that cloning human embryos—not just mice or rats as before—seemed practical, scientists in universities and companies decided they needed a new name, one that would bypass the public’s usual revulsion over the cloning of humans for scientific or commercial purposes.

Proponents of human cloning decided to deconstruct the single process into two identical processes—good “therapeutic cloning” to create embryos for use in medical transplants and bad “reproductive cloning” to create embryos for implantation and birth. Of course, this rhetorical trick also required scientists to argue that a cloned embryo was not human when destined for the laboratory bench or the tissue-bank, but was human when intended for birth. Thus many pro-cloning scientists now argue with a straight face that a cloned human embryo is only human when people say it is. Until that unscientific moment when opinion polls somehow breathe humanity into a human embryo, the cloned embryo remains property to be dismantled, diagnosed and disposed of, according to the owners’ wishes. It also gets a new identity—cleaved egg, ovasome, truck, pre-embryo, pluripotent stem cells, etc.—to distinguish it from other human embryos deemed worthy of life. Needless to say, no one calls the un-embryos “subhumans.”

Neither this new terminology nor this secular creationism has been challenged by any of the major newspapers—not in editorials nor in reporting. Translated into the dot-com scenario, such practices are akin to reporters accepting assurances from corporate executives that their financial losses are really investments and projected revenue is bankable cash. Come to think of it, that’s what many dot-coms did to hide their red ink, without it being described that way by reporters for months or years, until the Enron collapse precipitated the return of common sense.

Delivering What Reporting Promises

Cures that seemed so promising in the first wave of stem cell stories might never arrive, simply because there is too great a legal risk. The risk is that one or more of the millions of stem cells transplanted from a cloned un-human embryo into a patient will actually try to grow into a complete person. Each attempt will fail, of course, because the stem cell will have been extracted from its parent cloned embryo. But in the trying, such cells often now grow into “teratomas,” cancer-like growths of skin and bone, teeth and hair, and these would kill the patient.

Optimistically, assume the cloning scientists can control the process 99 out of 100 times. Those odds, while acceptable to dying patients, will likely ruin commercial prospects for any cloning-based therapy, especially when one adds the cost of custom cloning and considers marketplace competition from drug-makers, surgeons and the adult stem cell therapies.

Rival stem cell cures exist now, albeit in small numbers. Many cancer patients are treated with their own stem cells, and increasing numbers of patients with heart conditions, eye problems, brittle-bone disease, and multiple sclerosis are also being treated with modest but significant successes. These treatments, so far, show no sign of killing their patients.

But the major media typically ignore these advances and have even recently taken to labeling them as “cell therapy” or even just plain “stem cell” successes. This reporting tends to mask their current therapeutic advantage over the much-touted use of stem cells from cloned embryos. So far, no one has been treated with embryos’ stem cells, although proponents argue that the first clinical trials could begin in three to 10 years. That delay gives the technology of adults’ stem cell many years to run further ahead of the embryo technology.

Back in our comparative dot-com land, this misplaced focus is akin to reporters arguing that investors should embrace companies with high online market share or impressive stock valuations, rather than real products, actual profits, and satisfied consumers. But that is precisely what many reporters and TV anchors did when they focused attention on companies whose lack of bankable assets was supposedly countered by their coolness. Remember pets.com? Who can possibly forget clickmango.com, or Blue Mountain Arts, a dot-com company that was purchased for one billion dollars in cash and stock because it was expected to corner the market on electronic greetings cards? The buyer, by the way, has long since shut its doors, although the seller is living comfortably in Colorado.

Speaking of value, one should ask who gains from the optimistic focus on embryos’ stem cells? The answer is a few companies and a variety of universities and scientists who hope the technology will lead to higher stock prices on Wall Street, more federal grants, and greater prestige in the science community. Already, scientists working on adults’ stem cells say on the record—and with evidence to back them up—that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) favors the embryo stem cell technology that was developed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. (This, of course, is no surprise to Tommy Thompson, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, who previously served as governor of Wisconsin and who, in 2000, offered $150 million in state funds to boost local research on the technology.)

The NIH’s focus on this technology also serves the interests of the embryo scientists—and their many fans among science reporters—who want to use cloned embryos to learn more about early human development, both because of their desire to know and because of their desire to control the genetics of early human development. One hopes that such control would be used to develop various cures for diseases involving new types of drugs, for example. But it might be used for another purpose, such as earning plaudits needed for academic prizes. Or it could be used to win patents for the nascent genetic engineering industry, which hopes to profit from parents-to-be who are interested in shaping the development of their child while it is still in the un-human petri-dish stage of life.

One should also ask who loses if the focus remains on long-term research into human development. Arguably, the losers are the scientists who need grants to further develop the technology of adults’ stem cells and today’s patients who need short-term cures to save them before they die. That’s the not-implausible claim made from a wheelchair by James Kelly, who wants some of the money spent on using stem cells to repair spinal cords, including his own. Disillusioned by the NIH’s spending, he’s looking overseas for an adult stem cell cure. Even some advocates in the “patients groups”—mostly funded and overseen by the professionals and managers who treat the patients—have spoken out against the false promises of early cures from embryo research.

When translated back into the familiar terms of coverage of the dot-com bust, the media’s focus on embryo work is akin to reporting that vaporware—software that does not exist—is better than partly tested software. It is little different from reporting that a dotcom’s ambitious hopes to dominate online retail make it a better investment than retail chains with expertise, warehouses, customers and revenue.

Have journalists not learned from the dot-com bubble? Can we, as reporters, not restrain our wildest dreams in favor of accurately describing the limited, but still wonderful, progress that we observe?

Our key error seems to be unwarranted deference to professionals in the universities and sciences. This fosters a widespread reluctance to treat scientists (whether they’re sources, subscribers or friends) as who they really are—university-based entrepreneurs working in a complex of professional and commercial interests. Most scientists, along with many other professionals, prefer to downplay wealth while they compete for and then advertise the professional status that is often the key to wealth and further professional status.

The media’s deference to the scientists’ self-image is not universal, but it is routine. For example, both Rick Weiss at The Washington Post and Nicholas Wade at The New York Times—who report many of these stories—explained that they usually did not include in their articles mention of the financial interests of the scientists because these interests are so commonplace. In my interview with Wade, which I conducted while writing a freelance piece for The Washington Monthly, he also told me that readers are not interested in financial matters. And the approach these influential reporters take is similar to that taken by the vast majority of journalists who write and edit these stories.

But financial matters and professional rivalries are not merely “fit to print.” They’re central to the story of biotech, science and cloning.

Neil Munro covers the politics of science and technology for the National Journal in Washington, D.C. Previously, he covered the dot-com bubble for Washington Technology and the U.S. Department of Defense for Defense News.