My book was conceived in the days leading up to Christmas 2002 at Fort Benning, the vast Army installation in west central Georgia, just across the Chattahoochee River from Alabama. U.S. military officials consider Benning the world’s premier training ground for infantrymen, but there I was, with 59 other journalists, huffing and puffing my way through “media boot camp,” a Pentagon program designed to make reporters, photographers and broadcasters combat-ready.

There were 10 women in my class of 60, and we had what was regarded as a mark of distinction or pain in the rear: a documentary crew representing an Academy Award-winning documentar-ian was trailing our every move.

It puzzled me that they found women correspondents training for war so out of the ordinary; I didn’t think I was special. I’d been to some hot spots around the world, but so had many people in the class. The focus on the women trainees made me feel sorry for the men in the class, since they were being slighted, just as all of us were being pushed and prodded.

But after enduring the camera, the lights, and the microphone for five days, I had one overarching thought: If this is so interesting, I’ll tell my own story. It’s estimated that only roughly one in 10 of the 700-plus embedded journalists were women.

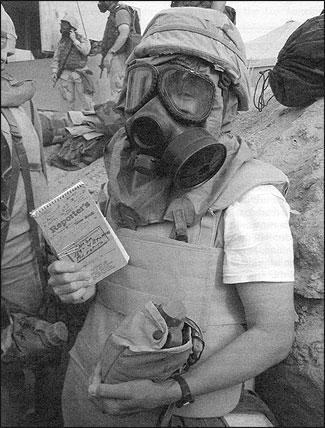

Reporter Katherine M. Skiba found herself on the other side of the lens when a missile alert sent soldiers from the 101st Airborne to a foxhole. A gas mask, helmet, bullet-resistant vest and canteen were standard equipment for embedded journalists. The photo was taken on the first day of the war in Iraq at Camp Thunder, a U.S. installation in Kuwait near the borders of Iraq and Saudi Arabia. It was the temporary home of the helicopter unit she accompanied, the 159th Brigade, part of the 101st Airborne Division. The brigade was the first U.S. military unit threatened by an enemy missile when the war began. Photo by Capt. Jeff Beierlein, 101st Airborne Division.

During the war in Iraq, I was assigned to the Army’s 101st Airborne Division, writing stories and shooting photographs for my paper, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and phoning my reports to its affiliated television and radio stations. After 45 days in the field, I returned home and launched into a book, the provisionally titled “Sister in the Band of Brothers: Bringing the War in Iraq Home to America.” As this was the first war to feature a large number of embedded journalists as well as popular use of the Internet, my stories were read coast to coast.

When I left for the war late in February, I had no idea whether I’d see any action—or so much bang-bang that I wouldn’t make it home alive as, sorrowfully, was the fate of 17 of our professional brothers and sisters. I ended up having a war that was chiefly three things: challenging, frightening and exhilarating.

I accompanied the 101st Airborne’s 159th Aviation Brigade, comprised of Black Hawk and Chinook helicopter pilots who ferried troops and supplies to the frontlines. Seven hours into the war, the unit, then in Kuwait near its borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia, had the distinction of being the first to be targeted by an Iraqi Ababil-100 missile, the crown jewel in Saddam Hussein’s arsenal. Traveling faster than the speed of sound, the weapon was destroyed nine miles from our camp by a U.S. Patriot guided missile. I lived out a nervous hour in a foxhole during the attack, mouthing the Act of Contrition and remembering the letter I’d penned to my husband just after President George W. Bush’s ultimatum to Hussein and his sons: “Marry someone nice,” I urged my husband. “Fish a lot. And forgive me for doing this.”

These days, I still ask my husband forgiveness since I’ve been spending hour after hour alone in my den with maps, photographs and my sand-coated notebooks, writing a memoir. Tom Vanden Brook, a reporter for USA Today, has proven to be an astonishingly understanding spouse. My editor, Marty Kaiser, was supportive of my request for a book leave, agreeing that a story like this might never come my way again. It would have been easier on many levels to take a long, post-war vacation and move on to the next story, but what I experienced left an indelible impression.

Writing the story of my war, from the “keyhole view” of the conflict I had side-by-side with about 1,700 soldiers, has meant discarding some of the cardinal rules of journalism that, after 25 years with metropolitan dailies, are nothing if not second nature. I’m no longer objective. I’m not taking pains to keep myself out of the story—since I’m the narrator. Plus, I weave in my husband Tom’s experience living alone back in the States, getting an overview of the war while working on his paper’s rewrite desk and wincing at the creature who came home speaking “Army,” which is to say, stringing together nouns and verbs laced with derivations of the F-word.

Speaking of language, I can swear in my book. I can use foreign words. I can use fancy words verboten in most newspapers. I can even invent words. All of that is delicious fun after one too many by-the-book copyeditors. But I now stand before copyeditors with enhanced respect—and belated gratitude—since, as Joni Mitchell counseled, “you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.” My book has demonstrated that I am not the precision grammarian I had fancied myself. Meantime, I’ve ditched my Journal Sentinel stylebook and, for the first time since college, picked up The Chicago Manual of Style. At midcareer, I’ve finally come to terms with a fetish—for dictionaries.

I’ve had to modify the style and pacing of my writing, since my early drafts of chapters—rife with short, choppy paragraphs—were judged “too staccato.” Rather than blurt out my best stuff to grab the reader at the beginning, I’ve learned to slow down, lead the reader by the hand, reveal things one at a time, hint, foreshadow, even tease—all while moving the narrative forward. Meanwhile, urged by my agent to “dig deeper,” I’ve learned a lot about myself, my motivations, and my past. I’ve made discoveries about my own marriage, too, and can assure everyone that after the book is done, I won’t be interviewing my husband again for some time. In June, two months after I’d returned from the war, Tom pointed out that he and I had never actually sat down and discussed whether I should go; it seemed to him a foregone conclusion on the part of the cyclone he had wed nine years earlier. That stung.

I regard authors differently now, never before appreciating the discipline, strength, staying power, and solitude needed for a 250-page book. Sure, I’ve done magazine pieces and multi-part series, but writing to this length is a new undertaking. I feel at times like I’m sewing a quilt, which is an odd metaphor since I’m not handy with a needle and thread. But I’ve held onto that image, since once the synopsis and chapter summaries were finished—a very good road map of the story—each subsequent chapter seemed no more intimidating than one more square of the quilt.

Keeping my focus has meant turning down social invitations left and right, and these, of course, multiplied when I came home safe and sound and the people who prayed for my safety wanted to see me in the flesh—and hear all about it. I apologize profusely when I turn down friends, fearing that they regard me as an arriviste, but I’m the same ink-stained scribe I always was, only trying to find an audience—something else I’d taken for granted all these years—and finish my story.

Katherine M. Skiba, a 1991 Nieman Fellow, is a Washington correspondent for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.