Before you do anything else, turn on your TV. Go to CNN, Fox News, MSNBC and the big three networks. Read your newspaper, especially the letters to the editor. Log onto www.dvidshub.net, the Army’s slick new Web site that provides video and still images of troops in Iraq and Afghanistan to news organizations nationwide, free.

Now try to figure out whose truth is true.

Welcome to our generation’s battle for hearts and minds, born in the shock and awe of America’s invasion of Iraq. It’s driven by politics, ratings, the sheer number of news outlets and Web sites available these days and, most importantly, the unquenchable thirst for power in Washington. This is the propaganda war within Gulf War II. Its roots are in Ground Zero, and I have been a willing participant. So, too, were many other reporters. A month after the terrorist strikes on the East Coast, I sat in the cargo hold of a C-17, its bay door open and our crew wearing oxygen masks as the Air Force dropped crates of humanitarian rations in the dead of night from 25,000 feet over Afghanistan. A few weeks later I was in Kuwait with a 1st Cavalry Division brigade.

These military events were legitimate stories, but also our coverage of them contained an obvious rah-rah component. We were, after all, reporting on events certain to reinforce the patriotism of Americans already supportive of President Bush and the war. It harkened back to the simpler era of Ernie Pyle journalism, and I relished it as any patriotic American at war would—especially with an enemy as easy to hate as al-Qaeda. But I also knew it couldn’t last as I stepped on the bus that took NBC’s David Bloom, The Washington Post’s Mike Kelly, and a dozen other journalists to our assembly areas in Kuwait’s northern desert.

Three months after Bloom and Kelly died while reporting from Iraq during the 2003 invasion, the positive stories had begun to fade, replaced by an increasingly combative media that saw in Iraq disturbing parallels to the war in Vietnam. Then came the whisper, “Why aren’t you reporting the good news stories?”

Embedding, I soon realized, had spoiled all of us.

Embedded With the Troops

Before the war, 775 journalists went into the field, including San Antonio Express-News photographer Bahram Mark Sobhani and me. We lived with two Air Force close-air support teams attached to a 3rd Infantry Division battalion that spearheaded the invasion, saw combat in five battles, and had too many close calls to count. Our work appeared in newspapers nationwide. Mark’s pictures were shown on “Nightline,” in Time, even in Field & Stream. (That was the shot of a soldier fishing at one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces in Baghdad, the one with a big lake. Call it Ernie Pyle photography.)

As in any new relationship, both sides were nervous. In the run-up to the war there were a series of highly publicized media “boot camps” sponsored by the Pentagon. I was at the first one, in Quantico, Virginia, and recall journalists in a bar wrestling with the issue of whether to wear gear supplied by the Marines for a five-mile march the following morning. We were told that 35 media outlets would be on hand to record our march along a hilly, tree-lined path that cut through the base. A New York Times reporter, among others, worried about that, but I wasn’t bothered. Launched in the shadow of the coming war, our boot camp was bound to be a big news story. It sure enough was, and I found the incestuous nature of the event surreal. At dawn, some reporters wore blue bulletproof vests with “TV” taped over them while being interviewed by their own networks.

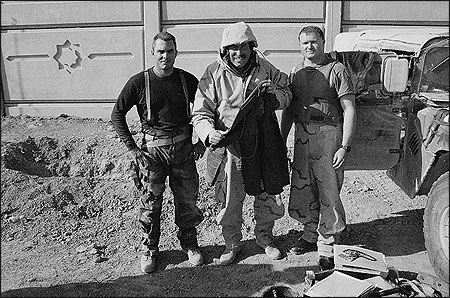

In the northern desert, Air Force Capt. Shad Magann, Senior Airman Dan Housley, and Staff Sgt. Travis Crosby were leery of taking on embeds. They wondered if they could talk about the war, its politics, and other matters without getting in trouble with their commanders. They soon found that these reporters, while indeed dubious about the war, nonetheless could be trusted. Our job was to report on American troops in combat, and we knew it was a great privilege and the adventure of our lives. We would protect our sources, as they certainly would defend us from the enemy. Determined to do it right, as Ernie Pyle had, I lived by a few rules, and just a few, for if you had too many you’d never remember them:

- Make it clear when they were being interviewed.

- Report only what I observed—not what I thought I saw.

- Check with them or the battalion’s commanders if I had questions about revealing details that could help Iraqis target our positions.

The romance blossomed. We were enthralled with the prospect of covering a war, the biggest story any reporter will ever get, and the troops began to like the media spotlight. A bonding began. I walked through the sprawling assembly area interviewing soldiers as they worked, played and slept. One day we caught a ride and happened upon a touch football game. Each night, after watching the beautiful desert sunset, I’d trek to one of the mess tents and talk with soldiers, who so often struck me as being too young. But then, at 46, I was old. The only man my age whom I met in the battalion I embedded with was its top enlisted man.

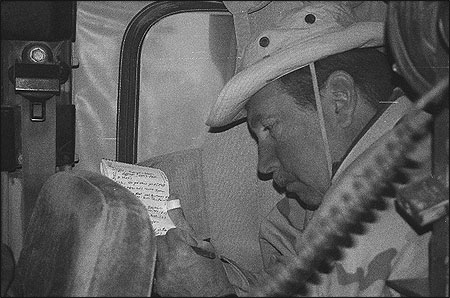

There were moments when I could almost hear Ernie Pyle’s voice as I filed stories under a camouflage net, my Toughbook computer resting on a small, rickety wooden table. Each morning I lined up with the troops to get prepared meals called T-rations, walked back to the tiny tent city we called “Air Force Village,” got pancakes specially made by some of the close-air support crew as they played heavy metal music, and then went to work. We could walk or catch a ride with someone, do our reporting, and then file. After turning in our work, we’d sit in a tent with other troops and watch DVD’s on television. One night I realized I didn’t want it to end. That’s how much I liked this life in Kuwait’s desert.

Mark and I had more experience with the military than many embedded reporters, but you could see the barriers fall with each passing day. There was the sense that we were in this together, but the troops lived by Ronald Reagan’s axiom, “trust but verify.” Some had computers, too, and carefully scoured the Internet to find our stories and photos. As they did, those soldiers came back and talked more.

I slowly got to know Housley and Magann, an A-10 Warthog pilot, by asking the usual Ernie Pyle questions. We had something in common: I’d worked in Shad’s hometown of Jacksonville, Florida and Dan’s hometown, Huntsville, Texas. Both trained at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. Dan, a typical trooper in the theater, was two years old when I started my career at The Huntsville Item. They were impressed as they saw an overweight middle-aged guy eat meals-ready-to-eat and learn to sleep on the Humvee’s hood, fighting off the cold.

The War Begins

Our first taste of combat came on a West Texas-like plateau defended by dug-in Iraqis, some regular army, others Republican Guard, and a militia wearing black pajama uniforms—the fedayeen Saddam. Shad drove like a madman to get to the plateau, rushing past several captured fedayeen next to a group of soldiers on a skirmish line. A pair of A-10’s circled like buzzards a few miles away after dropping bombs that from the distance looked like the tips of a ballpoint pen. Dust and debris blew high into the air as the bombs hit, the sound of their explosions reaching us seconds later. My heart was in my throat. It worsened when we got into the middle of the fighting, the air filled with machine-gun fire and the earth shaking as mortars exploded. Housley negotiated a particularly difficult dune as we raced to find a spot to call in air strikes.

“Young Housley,” Shad smiled, “the force is strong in you.”

Almost catatonic from fear up to this point, I managed a hearty laugh and soon settled down, taking notes while they led pilots on bombing runs. We lived that day only because an Iraqi gunner’s bullets fell 20 yards short of our truck.

Life with an Army at war was like this for weeks on end. Often I’d hear Pyle’s voice, and finally I understood the meaning of his words. There were long, boring days on the road, too many meals-ready-to-eat with the same, metallic taste. No showers for weeks and weeks. Crapping in the desert outside Najaf hoping the snakes, scorpions and Iraqi sniper who killed one of our tank gunners one day were in hibernation. Dying like that just seemed too low. Pyle loved the infantry, especially the lower-ranking troops, and I knew why. Living like this broke down the final barriers, as did the media’s mounting death toll. There was no lack of respect for the courage reporters displayed or the fact that they had volunteered for this, one of them being Kelly’s elderly friend George Wilson.

Shad, Dan and I endured four more battles. One, the taking of a bridge southwest of Baghdad, was so dangerous that Dan and I were certain we would not survive and said a prayer before we crossed. That night, during a counterattack, they grinned broadly as I phoned descriptions of the battle to my editors back in Texas. They then returned to the business of calling in air strikes that lit up the night sky, braving the bullets and rocket-propelled grenades that flew over our heads. Two days later we rolled into Saddam International Airport flush with victory. On a cool, star-filled night after the fall of Baghdad, the group that Sobhani and I were embedded with gathered next to the big lake at Al Faw Palace, broke out cigars, and told our favorite stories.

The brotherhood was complete, but my journey had only begun.

Returning to a Different War

Seven months later I was back in Iraq with Express-News photographer Ed Ornelas strapped into the cargo hold of a plane diving into old Saddam International with a gut-churning corkscrew landing. It was just after Thanksgiving, and the insurgency was heating up. The road from the airport to downtown already was the most dangerous in the country. The danger at Camp Anaconda, an hour north of Baghdad, was from mortars. In Baghdad we drove around town in a small, inconspicuous sedan, the threat coming from drive-by shootings and car bombs.

This was a much different war. Embedding, as we’d known it, was history. Reporters no longer were married to their unit for the duration, if only because this conflict had no discernible end. We stayed at Anaconda to interview AH-64D Apache Longbow pilots for a series, but broke off from them when we were ordered to Tikrit to report on Saddam’s capture. While there, we endured a hostile grilling from an American officer until he was convinced we really were reporters for Hearst Newspapers. Once nervous G.I.’s, fearing the specter of the car bomb, nearly fired on us when our Iraqi driver unwittingly drove too far at a checkpoint. After the Nabil Restaurant was blown up on New Year’s Eve, shaking the superstructure of my hotel miles away as the clock neared midnight, the cordon of troops that circled the ruins had the look of cops on the cusp of a big-city riot.

The euphoria of Baghdad’s fall that spring of 2003 had evolved into a struggle on the part of our occupation troops to survive the Iraqi winter. The following July, in 2004, Ed and I were back at old Saddam International. We rode an armored bus into town, the driver wearing a Kevlar vest and helmet. I sat on a long, rectangular block of ice and waited for an ambush like the last one, at the end of the invasion. The Green Zone was a prison, scarred by terrible suicide bomb attacks and the constant threat of mortar fire. Going anywhere required getting two soldiers to drive you around in a Humvee. Setting up stories turned out to be even more difficult. The 1st Cavalry Division’s public affairs office didn’t tell Ed and me about a raid on Haifa Street until afterward, ensuring there was no story. Efforts to spend an extensive amount of time at the combat support hospital were rebuffed by a public affairs office that at best was indifferent and at worst hostile to us. No explanation helped our cause. One public affairs officer caustically told me, “Maybe you’ll get lucky and someone will come here and die today.”

Marine Corps Times reporter Gordon Lubold, who flew out of Iraq on the same C-130 as Ed and me, found similar tension. He said things were “uneasy everywhere” and had heard of reporters who had been kicked out of units. “Military commanders have become extremely sensitive: A quote here or a sentence there that they don’t like or that they perceive paints them in a bad light can send them over the edge,” he said. “They’ve become increasingly suspicious of our motives.”

To be sure, there were many good moments. Our time with the U.S. Central Command’s No. 2 man, Lt. Gen. Lance Smith, led to the building of new bridges. We hung out a lot with troops from the Arkansas National Guard in Baghdad, guys who didn’t hesitate to tell you what they thought. Doctors and nurses at the 31st Combat Support Hospital were quick to talk with us and saved my life, treating me when my blood pressure spiked into the stroke zone. As with the first two trips, we’ve endured terrible danger and made lifetime friends. Somewhere out there, Ernie Pyle and his war correspondent buddies are smiling.

Blaming the Messenger

On the whole, however, I fear the mood has changed two years into the occupation. Media bashing is back with a vengeance. Quoting a columnist who talked of embedded reporters’ negative Iraq War coverage, Lt. Gen. James Conway told a Navy League conference last spring, “Remember, these reporters were being stuffed into wall lockers in high school by the types who now run our military. They’re just trying to get even.” I chuckle over that one; I was a defensive nose tackle with a Marine’s hardheaded attitude in high school.

Civilian Pentagon leaders, military commanders, and journalists at a 2003 Cantigny Conference hosted by the Mc- Cormick Tribune Foundation found the atmosphere between troops and media in Iraq much better than the bitter aftermath of Gulf War I in 1991, when tempers flared over limited access and specially chosen pool reporters who never saw a battle. But the conference participants wondered if embedding would work in a longer, more drawnout war with greater casualties, a logical question that already has been answered by Gulf War II, now in its third year with no clear exit strategy.

How to counter the drip-drip-drip of the dead and the maimed? Blame the media. Accuse us of overlooking the good news stories of Iraq. Moan, as conservative commentators often do on cable TV, about “liberal” newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post that are out to get the President. None of this is new. We heard it all from Richard Nixon, who often went to the well of his “silent majority” to marginalize opponents. Of course, conservatives have reason to be paranoid, for some of their critics would be after them no matter what. The same goes for liberals who feel under attack from the right. That isn’t new, either. Indeed, the “Crossfire” nation is really a cottage industry, not a political movement. (Just look at the clowns who’ve cashed in, using cable television to sell their books and perpetuate their existence as celebrities.)

What is new, and worthy of a serious conversation among politicians and their constituents, is the Digital Video & Imagery Distribution System (DVIDS), the Army-run Web site that feeds positive news and images to TV stations in the United States—at no cost. Technology is taking us where no American has gone before. The Army and its proponents say DVIDS provides a view of the war as captured by military public affairs that isn’t reported by the news media. They’re almost certainly right. Propaganda experts, including the University of Houston’s Garth Jowett, however, worry that the melding of technology, politics and lazy rip-and-read news outlets not given to crediting their sources deserves a Surgeon General’s warning. They’re right, too. Will people know the difference between news and official spin? The carping is as bad from the left, which has found fault with the national media for not challenging the administration during the run-up to the war and demands ever more critical coverage of the occupation. These folks make essentially the same supposition as those on the right: that the media could find more bad news stories if they just did their jobs.

I’m not saying journalists do everything right or that we couldn’t do better. But this is life in today’s supercharged environment, made possible by the glories of a society besotted by conspiracy theory and satisfied not with thoughtful answers that lead to solutions but scoring points against the opposition, rallying the base, pumping up cable TV ratings, and selling newspapers, magazines and books.

These are perhaps issues upon which reasonable minds can disagree, although I am deeply troubled at how quick Americans are to pick a fight with each other rather than find commonsense solutions on civil terms—a notion from my parent’s generation that seems to have little utility today. When I returned from the invasion, I channel-surfed from the rediscovered comfort of my living room couch for days on end and concluded that the country had lost its collective mind. A month after that stunning victory, we were at each other’s throats—again.

Yet even more disturbing is the Fort Bragg, North Carolina court-martial of Army Sgt. Hasan Akbar, sentenced to death in the killings of two fellow troops in an attack early during the invasion. Fort Bragg this past spring Read the letter sent to Defense Secretary Rumsfeld by MRE »required reporters to sign an “agreement” pledging not to talk to soldiers or civilians on the base without permission. Believe it or not, public affairs officers even followed reporters to the restroom. The post’s attempt to force reporters to trade their First Amendment rights for access to its courtroom sparked a confrontation between the Army and journalism groups led by Military Reporters & Editors (MRE), an organization I cofounded in 2002. We’ve vowed to go to court the next time that happens.

Trust Evaporates

That’s where we stand today, nearly four years after 9/11.

MRE supported embedding because it ensured that the media would gain access to the troops. But despite our gains, many of us who have worried about the relationship between the military and media fear we’re on a treadmill. Vietnam-era antagonism between the media and military is back. It’s especially strong in the Pentagon, where some I know among the press corps long ago lost faith in the integrity of Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld and other top civilians.

The hostility is mutual except for the symbiotic relationship between the administration, Fox News, and conservative talk-radio hosts. Our critics, most of them Bush backers, contend that the news media have deliberately tilted their coverage toward the negative side of the conflict. Many of us point out that news usually gravitates toward the bad. Car accidents, stabbings and shootings are the staple of local TV broadcasts. It’s a bit odd that people believe reporters risking their lives aren’t doing enough to find “good news” in a war zone—especially one as infested with insurgents, crime, corruption and decades of neglect as Iraq. It sounds downright crazy that a few think the reporting is politically driven.

Ernie Pyle found those “good news” stories in war-torn Italy and France, as have many of us in Iraq. But read his book, “Brave Men,” and you know that as much as Pyle loved the common soldier, he also hated the carnage of war and often wrote about it. Pyle would have been one of the original Iraq embeds, and he would have returned to the theater. Integrity mattered to him, so Pyle would have addressed the whining about a lack of good news, as we should today. He would have asked if our battle to win hearts and minds in a war many think has questionable origins and no clear end has exposed us to the very virus that led Saddam and pitiful Iraq to its ruin—an institutionalized indifference to the truth. And so in this land of the wedge issue it’s a good bet that Pyle would have been beloved by the troops and, ironically, reviled as a traitor in some quarters of our flag-waving nation, as well as the government that tacitly endorsed him.

Sig Christenson has been the military affairs writer for the San Antonio Express-News since 1997 and was an embedded reporter for Hearst Newspapers during the invasion of Iraq. He has returned to Iraq twice since then, working as both an embedded and independent reporter. He is president and cofounder of Military Reporters & Editors, a nationwide group of journalists specializing in coverage of America’s armed forces.