Move over, boomers. At 78 million between the ages of 39 and 57, you used to be the most coveted population in America. Until Generation Y, that is, who have you beat by about 10 million. At 16 to 24 years old, the older part of the Gen-Y’s are a powerful, cash-wielding, get-it-while-it’s-hot group of 32 million young adults, who spend about $200 billion annually and influence another $300-400 billion in spending.

While the 2003 Scarborough Report tells us that a healthy number of 18 to 24-year-olds regularly read a newspaper—38 percent nationally—there is no guarantee this will continue or the percentage will increase as they get older. In fact, there’s plenty to suggest it won’t. Newspapers are up against a behemoth we all know about, the Internet. There is also a potentially ruinous trend that most of us are just waking up to: This generation uses news differently than their parents and grandparents. If they can’t interact with it, they will go—and are going—elsewhere.

Searching for Solutions

What, then, will attract them to newspapers? What is the future of newspapers if they don’t start subscribing? Why are this generation’s newspaper reading habits so different from previous generations? In the newspaper business, all of us are asking these questions and scrambling to implement different solutions, usually partial ones—a teen page here, a tabloid section there, an entertainment spread somewhere else.

I don’t think anyone has yet found what we’d call “the solution.” This is perhaps because I don’t believe there is one, in the sense that a newspaper can do any one thing to capture young readers’ attention. What connects this generation to information and news is too complex to fit into our formulas. They are too savvy about marketing and too sophisticated to fall for a moderate tweak of the passive service most of us provide in our print product. It’s no longer enough to offer news and expect people to accept what we offer as the last word. Nor is it enough to allow the usual politicians and loudest voices to dominate the ink. Or to believe that “connecting to the community” only means printing a dozen letters to the editor each day.

This generation craves—no, demands—debate and participation in the news. Instead of waiting for news to reach them, often they determine what “news” is in their own blogs, in chat rooms, and in online forums. How they use news is all about hands-on debate and involvement in a continuous and evolving marketplace of ideas. By becoming pundits about issues affecting them and their peers, by being observers and commentators, they are breaking down what they perceive to be the elitist attitude of too many newsrooms. And they’re doing it all with the click of a mouse or the tap of a stylus and with a steady discourse about political and social issues and trends in their daily lives—trends most newspapers show no indication of knowing anything about.

An unmistakable example of this new communication tool is Weblogs. Most blogs are written by your average Jane or Joe who take on a pundit’s role by reading and thinking in a way that newspaper “experts” or usual sources rarely do. The few newspaper blogs that exist are hugely popular, largely because they allow the reader to see the journalist as a human being, connecting with them without the stiff, imperial we voice that turns so many younger people off. And most blogs allow—indeed, thrive on—reader interaction.

What Can Be Done?

To compete with the Internet and have a chance at attracting young people, newspapers must offer them a combination of goods: authentic and edgy news coverage, more international news, stories with more young voices, fresh writing and designs, interactive options such as blogs and forums and, perhaps most importantly, flexibility.

Letters to the editor? Lose ’em—unless you print almost all of them online, allowing the collection of comments to morph into a marketplace of ideas instead of today’s typical practice of selecting a few letters worthy enough to make the one page allotted daily to community dialogue.

Young reporters in the newsroom? Stop shunting them off to school board meetings and teaching them to write to the same 50-year-old white homeowner whom newspapers have always written to. Encourage them to weave whimsy into their news stories along with the facts, to write something they would enjoy reading. Instill in all reporters the need to consider different generations when reporting and writing, breaking down for young, old and in-between what the latest news means for them.

Write shorter but with substance and authority. This generation is all about quick-hit information gathering—not dumbed-down news, mind you, just shorter, smarter news stories. Many in this crowd stick to opinion pages where they can get both a sense of what happened and a point of view, so they can form their opinions and debate with peers, on and offline.

This crowd also craves more international news. It is the most ethnically diverse generation of any—6.8 million people in the United States describe themselves as being more than one race; of those, 42 percent are under 18, according to the Yankelovich’s summary of 2000 Census data. They realize they are part of the global system and, as such, want to know how they fit into it. Since the September 11th terrorist attacks, a majority in every generation indicate they are more interested in international news than two years ago, but it is members of Gen-Y who show the highest jump: 74 percent of them say “it is important to me to keep up with international news,” up from 65 percent prior to the attacks, according to Yankelovich.

Young people care about social issues and politics and want to know in particular how events in these realms relate to them. This is a smart bunch; they know the world is full of war and crime and injustice, but they also want to read about real people—locally and internationally—who are trying to make a difference.

As newspaper editors and managers, make some or all of these changes. But don’t expect newspapers to ever be able to cultivate the same loyal readers who turn only to your paper as the day begins. And this is a good thing. The world is too complex for anyone to read one paper, or look at one Web site, or listen to one news program.

Next appears every Sunday in The Seattle Times.

Next features opinion pieces by young writers.

The Seattle Times’s Approach

At The Seattle Times, we’re trying to attract and serve more young readers in a variety of ways. One piece of our strategy is Next, a fresh new opinion page written by and for young readers every Sunday in The Seattle Times’s op-ed section. On the Next Web site, readers find an expanded—and interactive—version of what appears in the newspaper. We are also starting a blog on the Next site called Nextopia. I am the editor of Next and, at 31, am close enough in age to the Next writers that we agree on much of what we’d like to see in Next and in newspapers in general.

Another piece is a companywide group of young people who examine the paper and look for ways to make it more appealing to youth, whether through specific story ideas, design suggestions, or bringing in young people to give us their opinions. Once the newspaper’s budget picture brightens a bit, we plan to conduct more research on local young people’s reading habits and desires.

Next is not the entire answer, but it’s one approach. And we’re seeing some good results. Close to 400 young people applied for 25 paid freelance positions. Healthy numbers of visitors check out the Next Web site and interact in online polls. Dozens of people send e-mails each week responding to Next stories and/or they submit guest columns for consideration. Nearly 300 high school and college educators use Next in the classroom each week through our Newspapers in Education program.

Once a month, over greasy pizza and cold pop, I meet with the Next team of freelance writers, all of whom are between 17 and 25 years old. These writers come armed with well-researched column ideas to present and debate with their peers and with several young Seattle Times’s staffers. We help them to focus their topics and steer them to sources. They have about three weeks to research and write each opinion column. I edit them and typically offer suggestions for revisions. Each Sunday, we print two to three columns on the page and run up to eight more a week online. We run nearly every letter on the Next Web site.

What sets Next apart from the rest of the paper are the personal perspectives of this diverse group of young writers. Readers don’t come to this page or the Web site for the freelancers’ writing or expertise; they come to hear from peers about issues that matter. Others come to these pages so they can connect with this younger generation. The writers aren’t afraid to get personal about everything from the struggles of living in a ghetto to being a young gay male and a practicing Catholic to one young minority’s fear of becoming “whitewashed” at a mostly white college.

Interestingly, Next freelancers often write about many of the same issues that members of older generations are concerned about. The main difference for our mostly young readers is not what they want to read about but how they want the story told: They want stories that help them understand what a particular issue means to them.

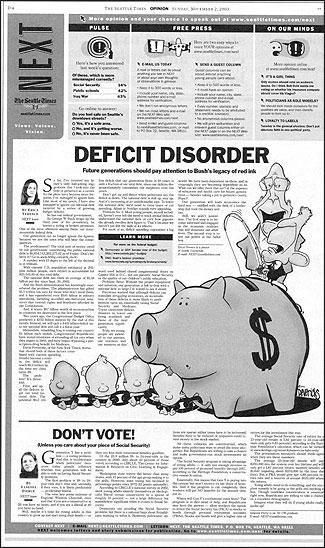

Social Security is a good example. Normally this topic seems incredibly remote to these younger readers, largely because much of the coverage is written with those 50 years old and older in mind. But here are some lines from a November story in Next about Social Security: “Generation Y has a problem—a voting problem. And this is troublesome when politicians’ decisions today greatly influence whether Gen-Y will be able to rely on having Social Security pensions.” The writer goes on to explain how few young people vote, which allows politicians to make Social Security promises to boomers, who do vote. The writer goes on to break down the declining funding picture of this entitlement program. “This means,” she writes, “that Generation Y is paying into the system now, but won’t receive its fair share of benefits.”

This is a good example of what Next tries to accomplish: writers breaking down complex political and social issues that matter to young people without losing substance or dumbing them down. Even as they include personal perspectives, opinions are always backed up by credible sources and relevant information.

In January 2004, Next will celebrate its one-year anniversary. We recently took a hard look at what works and, more importantly, what doesn’t and are implementing some changes this winter. We believe the stories need to be edgier and more locally focused, and we’re tweaking the page design and pushing more flexible layouts.

Next is a work in progress. And if progress means transforming valuable space in the paper one day each week and everyday online to create a place for young people to communicate with each other and the world, then we’re succeeding. After all, how many 22-year-olds’ opinions are respected—and printed—in a major metro paper? And how many older readers have a chance to understand and connect with the ideas and opinions of Gen-Y, told by members of Gen-Y themselves?

However, yes, Next is merely one page, one day a week dedicated to youth issues and opinions (though a few Next columns have appeared in the rest of the op-ed section). And it is on, as some of our writers lovingly refer to it, the “ghetto page,” the back page of the Sunday op-ed section.

Next is one piece of the puzzle. It’s a start to seeking out and including youth voices and issues throughout the paper, to creating a more interactive experience for readers, and to connecting on a human level with a huge sector of the community that otherwise might not pick up The Seattle Times.

To borrow a phrase from one of our Next writers, newspapers need to be “H.I.P.”—human, interactive and personal. We will never be able to compete with the Internet on a level playing field. But we can—and must—become H.I.P. if we want to continue to serve and cultivate readers.

Colleen Pohlig is assistant editorial page editor and Next editor at The Seattle Times.