White-clad mimes pose during Carnevale in Piazza San Marco, with three masked figures in the background providing counterpoint. Photo by © Frank Van Riper.

When it was The Most Serene Republic, a community of art and achievement that valued the individual and barely tolerated the Pope in Rome; when it was the undisputed nexus of eastern and western trade; when Lord Byron or Wagner or Dickens tarried in creative leisure among its palazzi and canali—when Thomas Mann’s doomed, depressive Aschenbach came to seek solace, only to find death—the traditional approach to the city was by boat and virtually the only point of entry was through the Plaza that honors St. Mark.

So begins the final draft of the introduction to “Serenissima: Venice in Winter,” my book-in-the-making and a labor of love with my wife, Judy Goodman. This project began quite unexpectedly 20 years ago, when Judy and I delayed our Italian honeymoon so I could cover the 1984 presidential campaign.

Back then, I had no inkling I would become a professional photographer, much less one who did photography books. But, in fact, the freedom to scratch this photographic itch, which had been with me since childhood, came five years before we went to Venice, during my Nieman year.

The time I spent that year in the darkroom at the Carpenter Center began to push me with unsubtle force away from covering politics for the (New York) Daily News and into joining my photographer wife in a commercial and artistic partnership that, like the marriage, has endured—even prospered—during these past two decades.

The Venice book was our first joint artistic venture. If there were bumps early on, I have forgotten them; the project simply has been too damn enjoyable. Sometimes we made two trips to Venice in a year and took up residence for as long as a month in an apartment in the sestiere of Santa Croce. On each trip, armed with research we’d done during the preceding months from books, interviews, films and chance encounters, Judy and I plotted a short list of places and people we needed to find—people at work, people shopping at La Pescaria, people enjoying a sunny Sunday in Campo Santa Margarita or at Il Giardini.

Doing this preparatory research confirmed that the reporting of a story can be as important as the end result. And it convinced me of the exponential magic of networking. For example, to make pictures of real glass blowing on Murano—not snapshots of some fellow fashioning a tiny glass horse before an audience of tourists—we followed the lead of one of our American clients. He told us of his neighbor Giovanni. Giovanni’s brother Giampaolo, it turns out, is one of Venice’s premier glass brokers. I called Giovanni, who called Giampaolo, who ultimately told us, “With me, you can do anything.”

He was right. After several hours watching and photographing some of the greatest glass artisans in the world, Giampaolo asked: “Would you like to see a palazzo?” And later that week, we did, and also met and photographed the count and countess who owned this stunningly restored palace in the heart of the city.

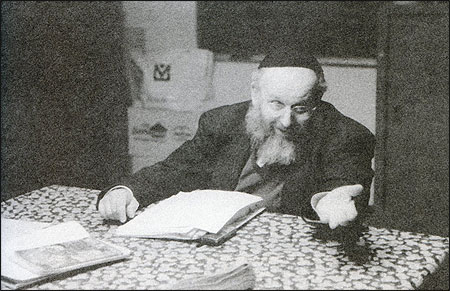

To document a key part of Jewish life in the world’s first ghetto, we talked with a photo lab owner (and orthodox Jew), who recommended we take a guided tour of the old Jewish cemetery on Lido. Two years later, that same guide led me to Rabbi Elia Richetti, who graciously let us photograph one of his afternoon Hebrew classes.

In the years since I left the Daily News, I have been able to pursue my twin loves of photography and writing, often while working on the same project. This has opened creative and artistic possibilities I never imagined that will soon culminate in the publication of this Venetian adventure. And to think it all began on those days when I went timidly but excitedly into the darkroom during my Brigadoon year at Harvard.

Frank Van Riper, a 1979 Nieman Fellow, is a photographer and author and, since 1992, photography columnist for The Washington Post. He previously was a Washington correspondent and editor in the (New York) Daily News’s Washington bureau. His current book, “Talking Photography” (Allworth Press, 2002) is a collection of the first 10 years of his photography writing.

In the Venice Ghetto, Rabbi Elia Richetti teaches a Hebrew class of young boys and girls. Photo by © Judith Goodman..jpg)

A gondolier plies the Venetian lagoon on a cold winter night as the church of La Madonna Della Salute looms in the background. Photo by © Frank Van Riper.

A traghetto (a smaller gondola) is the crosstown bus of Venice. For a very small fee, you can cross the canal without having to walk to a bridge. Many Venetians do this standing up. Photo by © Frank Van Riper.

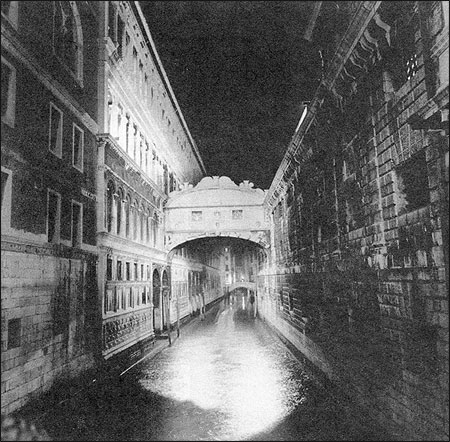

This is a late-night time exposure of the Bridge of Sighs between Doge’s Palace and the prison where unfortunates often would spend the rest of their lives. “Sighs” refers to an expression of despair from those glimpsing the light of day for the last time. Photo by © Frank Van Riper.