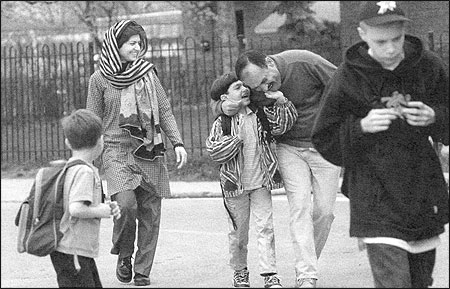

Pakistani parents pick up their sons at an elementary school they attend in Toronto. The family is seeking asylum in Canada after their visa expired in New York. Photo by Paul Kitagaki, Jr./The Sacramento Bee.

It wasn’t a particularly popular choice in some parts of the newsroom: The Sacramento Bee would not be sending any reporters or photographers to Iraq to cover the impending war. Yes, it was a huge story that would receive worldwide coverage. And yes, many large and medium-sized papers were sending staffers to Iraq either as embedded reporters and photographers or as unilateral reporters. There were certainly valid arguments for doing so, but these were not part of the reasoning I, as executive editor, used to arrive at the decision I did. And I reached this decision, in part, because I trusted that our readers would not be short-changed. I knew that we’d give them a solid selection of stories and photographs from reporters being sent by other McClatchy papers and the dozen or so wire services to which we subscribe.

Instead of incurring the large cost of covering the war, I wanted to concentrate our newsroom’s limited resources and time on a story of major national import that I thought wasn’t receiving the kind of scrutiny it deserved: the increasing controversy surrounding the USA Patriot Act, which Congress passed in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks. At a paper of our size—295,000 daily—editors often have to make choices on how best to deploy resources to deliver the most impact to readers. I knew that to do this story properly would require several months of investigative reporting; if reporters were in Iraq covering the war, the newsroom would not have the resources to enable a team of reporters and editors to take on this assignment.

Because of concerns I had about the lack of press attention to what might be happening with civil liberties in this country since the act’s passage, in February 2003 I asked senior writer Sam Stanton to begin taking an in-depth look at this issue in various communities around the country. I also told the editor of this project, Deborah Anderluh, to let the reporters travel to wherever they needed to go and to use reporters she needed to use to be sure the story would be fully told. Soon, immigration reporter Emily Bazar and photographer Paul Kitagaki, Jr. joined Stanton to make this a three-person reporting team.

During the next several months, Stanton, Bazar and Kitagaki traveled across the country and to Canada as they searched for information about and examples of how people’s lives have been affected by the USA Patriot Act. Their reporting led them to conclude that this legislation and a host of related government regulations was having a profound effect on many people’s lives. They found immigrants, primarily Muslims and others from the Middle East who legally immigrated to the United States, who were moving to Canada because they feared a government crackdown against them. They located immigrants who had overstayed their visas—a violation that in the past might have been ignored—who were now in jail as they awaited deportation hearings. They reported on immigrants who were being held incommunicado for indeterminate amounts of time.

But what became a four-part series of Page One stories went far beyond observing the impact this law was having on immigrants.

The reporters interviewed two Americans, both of whom were antiwar activists, who were blocked from boarding a plane in San Francisco because they were on a government-sanctioned “no-fly list.”

They spoke with a man who was questioned at his home by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on the day after he and six others, while working out in a gym, had engaged in a heated debate about religious fanaticism and the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan.

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, they found a former assistant public defender who was using a computer in the library at St. John’s College to search the Internet, when he was suddenly surrounded by four Santa Fe police officers who told him he was being detained by order of the FBI. He was taken to the police department and interrogated for more than an hour before being released.

They found peace groups who had been infiltrated by law enforcement officers and mosques that had been subjected to FBI surveillance.

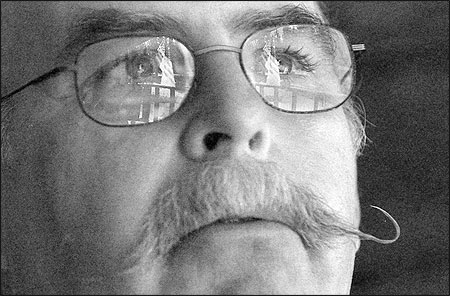

Tim Armstrong, a Vietnam veteran and Bronze Star Medal winner, lives in Juneau, Alaska, where the city council wanted to pass a resolution against endorsing the Patriot Act, a position Armstrong favored. Photo by Paul Kitagaki, Jr./The Sacramento Bee.

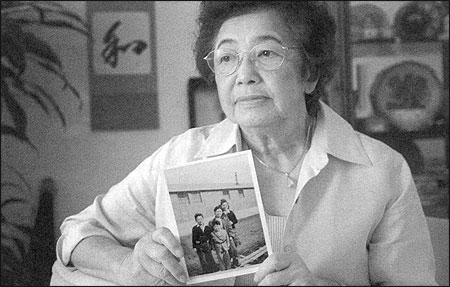

Marion Kanemoto, who now lives in Sacramento, was 14 when she was interned in the Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho. Her father decided to repatriate the family to Japan before the end of World War II. In the photo she holds, Kanemoto is with her brothers and mother at the internment camp. Photo by Paul Kitagaki, Jr./The Sacramento Bee.

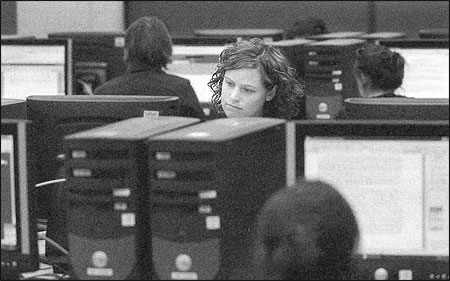

Students work on computers at the Sacramento State University library, where privacy policies were reviewed. Photo by Paul Kitagaki, Jr./The Sacramento Bee.

Documenting experiences such as these and others led our reporting team to understand that forces leading to a growing resistance to the erosion of civil liberties were emerging from both ends of the political spectrum. In Juneau, Alaska, diehard conservatives were rallying against these new policies, while in Salinas, California, the liberal-learning city council took a stand against the erosion of civil liberties. In the Bee’s own backyard, in the small Northern California community of Nevada City, more than 100 citizens packed a meeting hall in early March to debate these issues.

As our reporting continued, what became even more obvious to us than the reactions we were finding to this law was an absence of news about it. We could find no other news organization covering this story either nationally or as comprehensively as we’d set out to do. To track our findings, the reporters set up a computer file where each day they filed their notes, ideas and suggestions for graphics to accompany their words. The project’s editor met periodically with Managing Editor Joyce Terhaar and me to provide updates and receive feedback. It was a process that worked well.

While the reporters were finding many instances of how the law was interfering with civil liberties, documenting and quantifying its impact was harder. It was tough to convince immigrants, some of whom were the most severely affected by the new policies, to talk with us on the record. They feared retribution by the government. But with the help of community activists, lawyers and others, the reporters gained the immigrants’ trust, and they did not use information from anyone who would not go on the record. Figures were difficult to find, for example, to show the extent of detentions caused by implementation of this law or to determine how many people were on no-fly lists. This was caused, in part, by the government’s refusal to release much information, despite our newspaper filing of several Freedom of Information Act requests. When officials refused to disclose how frequently the USA Patriot Act had been used to require libraries to reveal what patrons were reading, Bazar convinced the California Library Association to survey its members for the Bee.

As a result of this reporting, in the same week Attorney General John Ashcroft reported to Congress that the FBI had never used the USA Patriot Act to gather information from libraries, the Bee was able to let its readers know that 14 libraries in California had been contacted by the FBI for patron information and that 11 had complied.

After we published this series of stories in September 2003, we received a tremendous response from throughout the country and the world. Some comments were negative, accusing us of being unpatriotic or “giving aid and comfort to the enemy.” But many expressed gratitude that these issues were being examined. Writing about the series in Editor & Publisher, columnist Nat Hentoff noted, “The Sacramento Bee did more than any daily newspaper I’ve seen to clarify the effects of the domestic war on terrorism on citizens and noncitizens.” And former President Jimmy Carter, who was sent a reprint of the series, penned a note to the reporters telling them, “I’m grateful you and the Bee have done this. Finally, the courts seem to be restraining Bush, Ashcroft and others who are chipping away at the Bill of Rights.”

Receiving such responses told me that we had made the right choice to concentrate our resources on reporting an important story that wasn’t being followed instead of following the obvious story and then being part of the pack.

Rick Rodriguez is The Sacramento Bee’s executive editor and senior vice president.