My wife, Elizabeth, likes to tell people how I took her to a strip mine for one of our first dates. Usually, though, she leaves out the fact that it was her idea. It makes for a better story, I guess. It was July 1998, and I was in the midst of reporting a series of articles that would become the biggest story of my career: mountaintop removal coal mining. I’m sure I talked about it constantly—the huge shovels and dozers, barren hillsides, buried streams, and coalfield residents who live with gigantic blasts shaking their homes and dust clogging their lungs.

Elizabeth wanted to see what the big deal was. So we went on a little picnic to Kayford Mountain. It’s a mountaintop removal site, just a 30-minute drive from downtown Charleston and the state’s gold-domed capitol building. On top of the mountain, Larry Gibson tends his old family cemetery. White crosses dot the spot, at the head of Cabin Creek. At the end of a long ride up a battered dirt road, the cemetery sits as a solitary island of grass, brush and scattered trees among the strip-mined moonscape.

Larry’s home place is surrounded on all sides by mountaintop removal. Various companies have mined thousands of acres in all directions. Larry’s little cemetery is the last holdout. Everyone else sold to the mining companies. “I told the company they could have my right arm, but they couldn’t have the mountain,” Gibson told me on my first visit there in April 1997. “We’re here, and we’re here to stay. They just don’t know it yet.”

Within a few months, the company—and everybody else—knew it. Later that year, in August, Penny Loeb reported a stinging exposé on mountaintop removal for U.S. News & World Report. “The costs are indisputable, and the damage to the landscape is startling to those who have never seen a mountain destroyed,” Loeb wrote. “Indeed, if mining continues unabated, environmentalists predict that in two decades, half the peaks of southern West Virginia’s blue-green skyline will be gone.”

Now it’s not like The Charleston (W. Va.) Gazette had never covered mountaintop removal before. My colleague, longtime investigator Paul Nyden, spent years uncovering coal-industry abuses and wrote numerous articles about mountaintop removal. But what Loeb’s work did was to give the issue national prominence, and it prompted those of us at the Gazette to delve into it more deeply.

Was the situation as bad as Loeb portrayed it to be? More importantly, if it was, how had it gotten that way? In 1977, Congress passed a federal law to regulate strip mining. Was it not working? Were state and federal regulators falling down on the job?

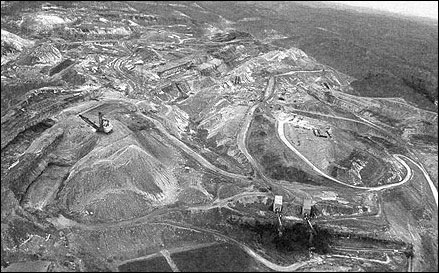

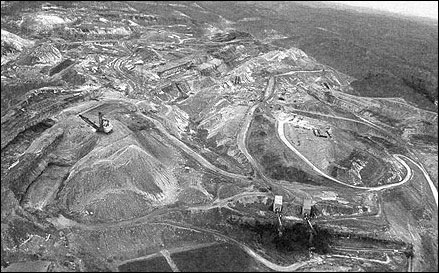

An aerial view of Arch Coal, Inc.'s Hobet 21 mine after it had stripped more than 10,000 acres from mountaintops in Boone County, West Virginia. Photo by Lawrence Pierce/Sunday Gazette-Mail, courtesy of The Charleston Gazette.

A Watchdog Emerges

After I got the okay from my editors, I started the hard work of digging through the documents to try to answer these questions. I read the 1977 law—the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). I also read SMCRA’s implementing regulations, the congressional history of the law, and as many law review articles on the subject as I could find. What I found became the basis for my stories: During arguments over SMCRA, Ken Hechler, then a Democratic congressman from West Virginia, tried to ban mountaintop removal altogether. As often happens, lawmakers compromised: mountaintop removal was allowed, but only under certain conditions.

Mountaintop removal is just what its straightforward name implies. Coal operators blast off entire hilltops to uncover valuable, low-sulfur coal reserves. Leftover rock and dirt—the stuff that used to be the mountains—is shoved into nearby valleys where it buries streams.

When Congress passed SMCRA, the lawmakers required coal operators to put strip-mined land back the way they found it. In legal terms, this means they must reclaim the land to its approximate original contour (AOC). Of course, when the top of a mountain is removed, achieving AOC is impossible. So lawmakers gave coal companies an option. They could remove mountaintops, ignore the AOC rule, and leave formerly rugged hills and hollows flattened or as gently rolling terrain. But to get a permit to do so, companies had to submit concrete plans that showed they would develop the flattened land after it was mined. Coal operators had to build shopping malls, schools, manufacturing plants or residential areas on their old mine sites.

I suspected this wasn’t really happening and decided to find out for sure. As so often happens in investigative reporting, this was tougher than I thought. The state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) told me it didn’t even know how many mountaintop removal mines had been approved. I then spent three months huddled at a table in a back office that DEP calls its file room. I befriended a couple of staffers there who seemed to be the only ones in the agency who knew where permit fields were, and I started combing through the records. Every mine permit file filled three to six thick binders. Each had hundreds of pages and dozen of maps and diagrams. DEP had changed the permit format several times over the years, so tracking specific items became more difficult.

Eventually I built my own database of dozens of mining permits. With it, I was able to pinpoint a shocking lack of enforcement by DEP and a complete absence of oversight by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining (OSM), the federal agency charged to make sure states properly enforce SMCRA.

How could this happen? Spending hour after hour in the DEP office looking through files helped me to answer this question. The agency’s permit writers, inspectors and various supervisors got to know me. They felt comfortable talking to me, and we’d spend hours sitting and chatting over permit maps or reclamation cross-section drawings. As it turned out, DEP previously had a rule that any mine that chopped off 50 or more feet off a mountain had to get an AOC variance. But at OSM’s urging, that rule was eliminated. Any mine—no matter what kind of changes it made to the terrain—could get a permit as an AOC mine. DEP staff who knew and trusted me told me about this policy and gave me the public records to explain it.

Sixty-one of the 81 mountaintop removal permits that I examined were approved, even though they did not propose or contain AOC variances. In May 1998, I published a long Sunday piece that detailed my findings. I led by describing two DEP staffers’ reactions when I asked them about how one huge mountaintop removal mine that was being left flat could possibly meet the AOC rule. The DEP staffers just laughed. “Approximate original contour is the heart of the federal strip-mining law,” I wrote. “But among many West Virginia regulators, it’s becoming a joke.”

Next, I turned to the post-mining development plans. It turned out that, even when DEP required AOC variances for mountaintop removal mines, it didn’t require development plans. I returned to the file room for another three months of research. A few of the DEP staffers I’d talked with before were a little less helpful after my story showed their agency wasn’t doing its job. But most of them wanted to do a good job policing the coal industry and were proud of their efforts and upset when politicians up the line got in the way of tough enforcement. I’ve found that most regulatory agencies are like this: the on-the-ground people work hard and want to do a good job, so if reporters show them they will be thorough and fair—and can be trusted—they will be helpful.

After more research, I was able to find 34 mountaintop removal permits with AOC variances. Only one included a post-mining development plan. There, the state built a prison. The AOC variance permits usually called for post-mining land uses such as pastureland, hayland or something called “fish and wildlife habitat and recreation lands.” In simple terms, coal operators were leaving mountaintop removal sites—more than 50 square miles of land that used to be some of the richest and most diverse forests in North America—as leveled off grassland.

I published another lengthy Sunday article that explained how coal operators had gotten away with ignoring the post-mining development responsibilities and, in doing so, had broken the social compact that allowed mountaintop removal to continue in the first place.

The Follow-Up Investigations Continue

These stories were published about six years ago. Since then, it’s been a pretty wild ride. When fellow reporters ask me what I’m working on, I almost always say, “mining stories—still more mining stories.” That’s because the controversy about mountaintop removal has only grown since that day Elizabeth and I made our visit to Kayford Mountain.

There was a series of investigations to follow-up on what my stories alleged. Eventually, the OSM published a report that confirmed my findings—and promised reforms of the permitting process.

Then there were the lawsuits. The West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and other groups have filed a series of cases in federal court to try to force proper enforcement of the permit requirements for mountaintop removal. So far, there have been three major federal court and one state court assault on mountaintop removal. Two of the federal court suits resulted in rulings by the now-late U.S. District Judge Charles H. Haden II to strictly limit the mining practice. Both were later overturned on appeal. The third federal court and the state court suit are still pending. I’ve covered all of these cases, attempting to master and explain in simple language the complicated matters from Clean Water Act permitting schemes to the 11th Amendment constitutional prohibitions against suing state governments in federal court.

My paper and I have also taken a lot of heat. After one of Haden’s rulings, the United Mine Workers of America protested outside the federal courthouse and picketed outside the Gazette’s offices. Coal industry officials and various business leaders frequently call and write to the newspaper to complain that our coverage of mountaintop removal is hurting the state’s economy. In a small and extremely poor state, such charges are taken seriously. They can create incredible pressure for a paper to back off.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that the only way to counter such pressures is with good, solid reporting. This is where the months I spent reading mining regulations and studying dozens of mine permits paid off. I was armed with the facts, and that made my reporting stand up to all levels of criticism.

The other thing I’ve learned is that it’s important to be able to give readers solid information about the economic impacts of environmental regulation. For example, through a federal Freedom of Information Act request, I discovered government studies that showed that the economic impacts of tougher mountaintop removal regulations were not nearly as drastic as the coal industry would have had people believe.

Reporting on this impact study took me back to when I began covering mountaintop removal. The environmental impacts from this practice are extreme—more than 700 miles of Appalachian streams have been buried and tens of thousands of acres of forests destroyed. That alone makes this a huge story, obviously. But my original series focused on a somewhat different aspect of this same issue: the social compact that allowed mining companies to destroy the environment, if they leave something for coalfield communities to live on when the coal is gone. The lack of regulation that allows hundreds of miles of streams to be buried also left the communities where this mining occurred without the economic benefits of new factories, schools, commercial centers, or parks. These facilities were promised to communities when lawmakers struck a bargain to allow mountaintop removal to continue.

Since my original series, I’ve written hundreds of stories about mountaintop removal. The subject has drawn the attention of every major newspaper, wire service, and TV network in the country. For the most part, stories done by outside news organizations focus on the environmental damage with the theme being a jobs vs. the environment fight. That’s a simple story line that reporters, editors and media consumers are used to seeing and hearing. But most environmental issues are more complicated than that, and this one is particularly complex.

The real legacy of mountaintop removal is not just the scarred land and buried streams—or a battle of jobs vs. the environment—but the missed opportunities that proper regulation of the post-mining development rules would have provided to America’s coalfields and to those who mined them.

Ken Ward, Jr. has covered the environment for The Charleston (W.Va.) Gazette for more than a decade.

Elizabeth wanted to see what the big deal was. So we went on a little picnic to Kayford Mountain. It’s a mountaintop removal site, just a 30-minute drive from downtown Charleston and the state’s gold-domed capitol building. On top of the mountain, Larry Gibson tends his old family cemetery. White crosses dot the spot, at the head of Cabin Creek. At the end of a long ride up a battered dirt road, the cemetery sits as a solitary island of grass, brush and scattered trees among the strip-mined moonscape.

Larry’s home place is surrounded on all sides by mountaintop removal. Various companies have mined thousands of acres in all directions. Larry’s little cemetery is the last holdout. Everyone else sold to the mining companies. “I told the company they could have my right arm, but they couldn’t have the mountain,” Gibson told me on my first visit there in April 1997. “We’re here, and we’re here to stay. They just don’t know it yet.”

Within a few months, the company—and everybody else—knew it. Later that year, in August, Penny Loeb reported a stinging exposé on mountaintop removal for U.S. News & World Report. “The costs are indisputable, and the damage to the landscape is startling to those who have never seen a mountain destroyed,” Loeb wrote. “Indeed, if mining continues unabated, environmentalists predict that in two decades, half the peaks of southern West Virginia’s blue-green skyline will be gone.”

Now it’s not like The Charleston (W. Va.) Gazette had never covered mountaintop removal before. My colleague, longtime investigator Paul Nyden, spent years uncovering coal-industry abuses and wrote numerous articles about mountaintop removal. But what Loeb’s work did was to give the issue national prominence, and it prompted those of us at the Gazette to delve into it more deeply.

Was the situation as bad as Loeb portrayed it to be? More importantly, if it was, how had it gotten that way? In 1977, Congress passed a federal law to regulate strip mining. Was it not working? Were state and federal regulators falling down on the job?

An aerial view of Arch Coal, Inc.'s Hobet 21 mine after it had stripped more than 10,000 acres from mountaintops in Boone County, West Virginia. Photo by Lawrence Pierce/Sunday Gazette-Mail, courtesy of The Charleston Gazette.

A Watchdog Emerges

After I got the okay from my editors, I started the hard work of digging through the documents to try to answer these questions. I read the 1977 law—the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). I also read SMCRA’s implementing regulations, the congressional history of the law, and as many law review articles on the subject as I could find. What I found became the basis for my stories: During arguments over SMCRA, Ken Hechler, then a Democratic congressman from West Virginia, tried to ban mountaintop removal altogether. As often happens, lawmakers compromised: mountaintop removal was allowed, but only under certain conditions.

Mountaintop removal is just what its straightforward name implies. Coal operators blast off entire hilltops to uncover valuable, low-sulfur coal reserves. Leftover rock and dirt—the stuff that used to be the mountains—is shoved into nearby valleys where it buries streams.

When Congress passed SMCRA, the lawmakers required coal operators to put strip-mined land back the way they found it. In legal terms, this means they must reclaim the land to its approximate original contour (AOC). Of course, when the top of a mountain is removed, achieving AOC is impossible. So lawmakers gave coal companies an option. They could remove mountaintops, ignore the AOC rule, and leave formerly rugged hills and hollows flattened or as gently rolling terrain. But to get a permit to do so, companies had to submit concrete plans that showed they would develop the flattened land after it was mined. Coal operators had to build shopping malls, schools, manufacturing plants or residential areas on their old mine sites.

I suspected this wasn’t really happening and decided to find out for sure. As so often happens in investigative reporting, this was tougher than I thought. The state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) told me it didn’t even know how many mountaintop removal mines had been approved. I then spent three months huddled at a table in a back office that DEP calls its file room. I befriended a couple of staffers there who seemed to be the only ones in the agency who knew where permit fields were, and I started combing through the records. Every mine permit file filled three to six thick binders. Each had hundreds of pages and dozen of maps and diagrams. DEP had changed the permit format several times over the years, so tracking specific items became more difficult.

Eventually I built my own database of dozens of mining permits. With it, I was able to pinpoint a shocking lack of enforcement by DEP and a complete absence of oversight by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining (OSM), the federal agency charged to make sure states properly enforce SMCRA.

How could this happen? Spending hour after hour in the DEP office looking through files helped me to answer this question. The agency’s permit writers, inspectors and various supervisors got to know me. They felt comfortable talking to me, and we’d spend hours sitting and chatting over permit maps or reclamation cross-section drawings. As it turned out, DEP previously had a rule that any mine that chopped off 50 or more feet off a mountain had to get an AOC variance. But at OSM’s urging, that rule was eliminated. Any mine—no matter what kind of changes it made to the terrain—could get a permit as an AOC mine. DEP staff who knew and trusted me told me about this policy and gave me the public records to explain it.

Sixty-one of the 81 mountaintop removal permits that I examined were approved, even though they did not propose or contain AOC variances. In May 1998, I published a long Sunday piece that detailed my findings. I led by describing two DEP staffers’ reactions when I asked them about how one huge mountaintop removal mine that was being left flat could possibly meet the AOC rule. The DEP staffers just laughed. “Approximate original contour is the heart of the federal strip-mining law,” I wrote. “But among many West Virginia regulators, it’s becoming a joke.”

Next, I turned to the post-mining development plans. It turned out that, even when DEP required AOC variances for mountaintop removal mines, it didn’t require development plans. I returned to the file room for another three months of research. A few of the DEP staffers I’d talked with before were a little less helpful after my story showed their agency wasn’t doing its job. But most of them wanted to do a good job policing the coal industry and were proud of their efforts and upset when politicians up the line got in the way of tough enforcement. I’ve found that most regulatory agencies are like this: the on-the-ground people work hard and want to do a good job, so if reporters show them they will be thorough and fair—and can be trusted—they will be helpful.

After more research, I was able to find 34 mountaintop removal permits with AOC variances. Only one included a post-mining development plan. There, the state built a prison. The AOC variance permits usually called for post-mining land uses such as pastureland, hayland or something called “fish and wildlife habitat and recreation lands.” In simple terms, coal operators were leaving mountaintop removal sites—more than 50 square miles of land that used to be some of the richest and most diverse forests in North America—as leveled off grassland.

I published another lengthy Sunday article that explained how coal operators had gotten away with ignoring the post-mining development responsibilities and, in doing so, had broken the social compact that allowed mountaintop removal to continue in the first place.

The Follow-Up Investigations Continue

These stories were published about six years ago. Since then, it’s been a pretty wild ride. When fellow reporters ask me what I’m working on, I almost always say, “mining stories—still more mining stories.” That’s because the controversy about mountaintop removal has only grown since that day Elizabeth and I made our visit to Kayford Mountain.

There was a series of investigations to follow-up on what my stories alleged. Eventually, the OSM published a report that confirmed my findings—and promised reforms of the permitting process.

Then there were the lawsuits. The West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and other groups have filed a series of cases in federal court to try to force proper enforcement of the permit requirements for mountaintop removal. So far, there have been three major federal court and one state court assault on mountaintop removal. Two of the federal court suits resulted in rulings by the now-late U.S. District Judge Charles H. Haden II to strictly limit the mining practice. Both were later overturned on appeal. The third federal court and the state court suit are still pending. I’ve covered all of these cases, attempting to master and explain in simple language the complicated matters from Clean Water Act permitting schemes to the 11th Amendment constitutional prohibitions against suing state governments in federal court.

My paper and I have also taken a lot of heat. After one of Haden’s rulings, the United Mine Workers of America protested outside the federal courthouse and picketed outside the Gazette’s offices. Coal industry officials and various business leaders frequently call and write to the newspaper to complain that our coverage of mountaintop removal is hurting the state’s economy. In a small and extremely poor state, such charges are taken seriously. They can create incredible pressure for a paper to back off.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that the only way to counter such pressures is with good, solid reporting. This is where the months I spent reading mining regulations and studying dozens of mine permits paid off. I was armed with the facts, and that made my reporting stand up to all levels of criticism.

The other thing I’ve learned is that it’s important to be able to give readers solid information about the economic impacts of environmental regulation. For example, through a federal Freedom of Information Act request, I discovered government studies that showed that the economic impacts of tougher mountaintop removal regulations were not nearly as drastic as the coal industry would have had people believe.

Reporting on this impact study took me back to when I began covering mountaintop removal. The environmental impacts from this practice are extreme—more than 700 miles of Appalachian streams have been buried and tens of thousands of acres of forests destroyed. That alone makes this a huge story, obviously. But my original series focused on a somewhat different aspect of this same issue: the social compact that allowed mining companies to destroy the environment, if they leave something for coalfield communities to live on when the coal is gone. The lack of regulation that allows hundreds of miles of streams to be buried also left the communities where this mining occurred without the economic benefits of new factories, schools, commercial centers, or parks. These facilities were promised to communities when lawmakers struck a bargain to allow mountaintop removal to continue.

Since my original series, I’ve written hundreds of stories about mountaintop removal. The subject has drawn the attention of every major newspaper, wire service, and TV network in the country. For the most part, stories done by outside news organizations focus on the environmental damage with the theme being a jobs vs. the environment fight. That’s a simple story line that reporters, editors and media consumers are used to seeing and hearing. But most environmental issues are more complicated than that, and this one is particularly complex.

The real legacy of mountaintop removal is not just the scarred land and buried streams—or a battle of jobs vs. the environment—but the missed opportunities that proper regulation of the post-mining development rules would have provided to America’s coalfields and to those who mined them.

Ken Ward, Jr. has covered the environment for The Charleston (W.Va.) Gazette for more than a decade.