As a cub reporter at The Associated Press in the early 1960s, Kelly Tunney was captivated by the stories she heard from her older co-workers. There was Frank “Pappy” Noel, her colleague in Tallahassee, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer who, on assignment covering the Korean War, was captured and held for nearly three years in a Communist prison camp. Later, in the AP Washington bureau, Tunney worked beside Vern Haugland. On assignment in the Pacific during World War II, Haugland parachuted out of an Army plane that ran out of fuel over New Guinea. When he was rescued after 43 days of hiding in the jungle, he weighed just 95 pounds.

While the veterans gladly shared their tales in the newsroom, Tunney often thought it was a shame that their vivid, sometimes swashbuckling accounts of “how I got that story” were not captured systematically by AP and shared more widely.

“There were all these people with all these stories. And we had no place to save the stories because in the AP it’s a daily run,” Tunney recalled in a recent interview.

Nor were there systematic efforts to preserve and carefully catalog the wire service’s internal communiques, some of them dealing with weighty editorial and ethical issues — like AP’s firing of correspondent Ed Kennedy after he defied a U.S. military embargo on news of the Nazi surrender in 1945. At the military’s request, reporters from Allied countries were still sitting on the news of the war’s end more than 12 hours after the formal surrender, but when Kennedy learned German radio had already reported it, he phoned the AP’s London bureau, which quickly put it on the wire. Years later, Tunney still heard newsroom veterans debating whether Kennedy was right to break the embargo — and whether then-general manager Kent Cooper was right to fire him for doing so.

Kennedy’s dismissal had a fascinating backstory. But for decades it remained largely buried in the bowels of 50 Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, AP’s headquarters for 65 years, where papers saved by AP board chairs, newsroom executives, editors, and correspondents were dumped in boxes and file cabinets, uncatalogued, gathering dust, and forgotten.

Or nearly forgotten, until 2003, when a sequence of events led AP to invest in an unprecedented program to save and organize decades worth of artifacts and papers — old typewriters and cameras, letters, memos, diaries, oral histories, and much more — to document the history of one of America’s major media companies. These materials give important context to both AP’s journalism and to the business decisions taken as the wire service grew and evolved over many decades — particularly in the pre-digital age, when managers and reporters exchanged lengthy typewritten messages, free of concern that their candid thoughts might be shared globally on social media. Archives such as AP’s are also vital in shedding light on issues beyond journalism, especially at a time when layoffs and high staff turnover mean less institutional knowledge across the industry.

“You might want to understand a political action or how it played out — not because you’re interested in learning about the AP, but you want to know the decisions that editors made on publishing stories or not publishing them,” said John Maxwell Hamilton, a longtime journalist and journalism historian at Louisiana State University. “The press is an important political institution. So, we should — to the extent we can — we should preserve their past.”

By 2003, Kelly Tunney had risen through the ranks of reporting, moved into management, and had been named vice president for communications at AP. Tunney knew about the boxes and the files; she occasionally added items to them herself, like a congressional press card issued in 1875 to Lawrence Gobright, who covered Abraham Lincoln for AP (Gobright’s card had apparently been passed down through generations of AP correspondents; a colleague about to retire passed it to Tunney).

Tunney also knew in 2003 that those long-neglected papers were endangered. AP was preparing to move from Rockefeller Plaza to new offices across town, and she worried that the move would be preceded by a call for spring cleaning throughout the organization, which might mean the basement files would be purged.

Tunney says her pleas to preserve AP history had gone nowhere in the past. But now, with the move looming and new management arriving — Tom Curley, president and publisher of USA Today, had just been appointed president and chief executive officer of AP — Tunney saw an opportunity.

“I’ll never forget Kelly’s pitch. She stood at the door, 30 feet from my desk, as if she were radioactive,” Curley recalled in a recent interview. “And she was so passionate about it.” AP, Tunney argued, needed a well-organized archive to preserve its century-and-a-half history. That history could enlighten today’s AP managers about past decision-making and enable journalism researchers to explore how America’s premier wire service had covered wars, dealt with censorship, and evolved into a global news network.

“The press is important as a political institution. … So we should preserve their past.”

—John Maxwell Hamilton, journalism historian at Louisiana State University

Curley’s response was an emphatic yes. Looking back on that decision recently, he said: “I don’t think anybody really knew what treasures were in those archives and how much original source material was there.” Nor did Curley know that revelations from the archives would lead him to make a very public apology on behalf of AP, 67 years after Ed Kennedy’s firing.

In helping to finish the book “Newshawks in Berlin: The Associated Press and Nazi Germany,” I got a first-hand look at some of those treasures Curley was referring to. That book, published in March 2024, was researched and written by my late husband, Larry Heinzerling, and his AP colleague Randy Herschaft.

Though they consulted a wide range of resources, some of the telling stories about the wire service's coverage of World War II came out of the AP Corporate Archives, like the remarkable action taken by the Chesapeake Association of the Associated Press in 1940. The association’s editors, from The Baltimore Sun, the Annapolis Capital, and other regional papers, believed that AP was exaggerating Nazi successes as the German military rolled swiftly across Europe that year. As subscribers, they were all paying AP for its reporting — which they voted unanimously to censure, charging that the Berlin bureau chief at the time, Louis Lochner, was “spreading Hitler’s views” and “has swallowed Hitler’s propaganda ‘hook, line and sinker,’” according to the group’s September 1940 meeting minutes, which were preserved in the archives. The archives also revealed that Kent Cooper told his directors the Chesapeake editors had condemned AP’s reporters “because they had told the truth” that Germany’s Blitzkrieg was indeed sweeping up victories across Europe. The board sided with Cooper’s view and voted to send “affectionate regards” to all AP war correspondents.

The story of the Chesapeake editors is a reminder that journalists face a perennial criticism in covering conflicts: accusations, including from colleagues in the business, that their reporting favors one side or the other. It’s just one example where archives like AP’s can put the experiences of today’s journalists in historical context.

“If you think it’s important to know about events in history because they show patterns, and illustrate those patterns,” said Hamilton, “then you have to have those [archival] libraries.”

AP’s corporate archives are separate from the news story and photo files the AP has produced over its 180-year history. In the pre-digital age, newspapers kept bound copies of their back issues and clipped each day’s stories to tuck away in the subject files of an office “morgue,” or research library. The morgue, which preserves the organization’s finished journalism, is sometimes referred to as the archives.

AP stories, once preserved manually as they flowed off the teletype by news librarians, are now preserved in a digital repository. AP text, photos, videos, and graphics can all be licensed online. But while AP’s online “morgue” preserves its journalism, it’s the personal papers and institutional records in the corporate archives that tell the story behind the story — the reporting adventures, the editorial decision-making, relationships with AP members, the administrative governance — that Tunney sought to preserve. And, AP’s archives have led to partnerships with companies like Ancestry and ProQuest that offer online research products; both companies have digitized portions of the archives, making them accessible to researchers online and producing royalties for AP.

Similar records exist at other news organizations, of course, but few, if any, have committed to the methodical acquisition, cataloguing, and preservation, overseen by a professional archival staff and maintained in-house, that are hallmarks of the AP Corporate Archives.

At the New York Times, for instance, longtime reporter David Dunlap maintains a small museum of artifacts inside Times headquarters, ranging from a copy of the paper’s first edition to the zip ties used in handcuffing a Times reporter covering a Black Lives Matter protest. There’s the vast "morgue" of clippings and photos housed in basement-level rooms near Times headquarters. And there are decades-worth of corporate records and individual journalists’ papers that were donated to the New York Public Library in 2007. But many of the Times’ records — including the papers of four recent executive editors Joe Lelyveld, Howell Raines, Bill Keller, and Jill Abramson — are privately held, making them difficult to access. “You’d think The New York Times would be better organized,” said Adam Nagourney, a Times reporter who told me in January that he had to approach each of the former editors individually for permission to see their files when he was writing his book “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn and the Transformation of Journalism.”

“The Times doesn't maintain a discrete, unified, curated journalistic archive,” confirmed Samuel Zucker, the paper’s manager of corporate records. “Instead, journalists' papers wind up in all sorts of private and institutional hands. There is not so much an institutional policy as there is a good-faith effort to find the best possible repository for archival resources, as the need arises.”

AP’s corporate archives are also not one-stop shopping. Journalists and executives have often donated their professional papers to their alma maters or other academic institutions. The early papers of Kent Cooper, for example, are at Indiana University, while the Wisconsin Historical Society’s archives hold those of Louis Lochner. Some records have just been lost. There are relatively few papers from several general managers, the agency’s top job, including Wes Gallagher, who led the AP during a critical period when the agency covered the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the Apollo missions, and the assassinations of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

But more systematic collection of both institutional records and personal papers became company policy after July of 2003, when Tunney hired Valerie Komor, then-director of prints, photographs, and architectural collections at the New-York Historical Society. Komor arrived at AP with no journalism background. More than twenty years later she is still there, very much a part of AP but still “an archivist to the bone,” said Tunney.

Before anyone else could delve into AP’s archival past, Komor, working alone in the Rockefeller basement, had to put the chaotic files in order. “In 2003, my work was looking for documents and gathering them in,” she said. “I looked in all the storage rooms [at Rockefeller Plaza], built some shelving, and started collecting.”

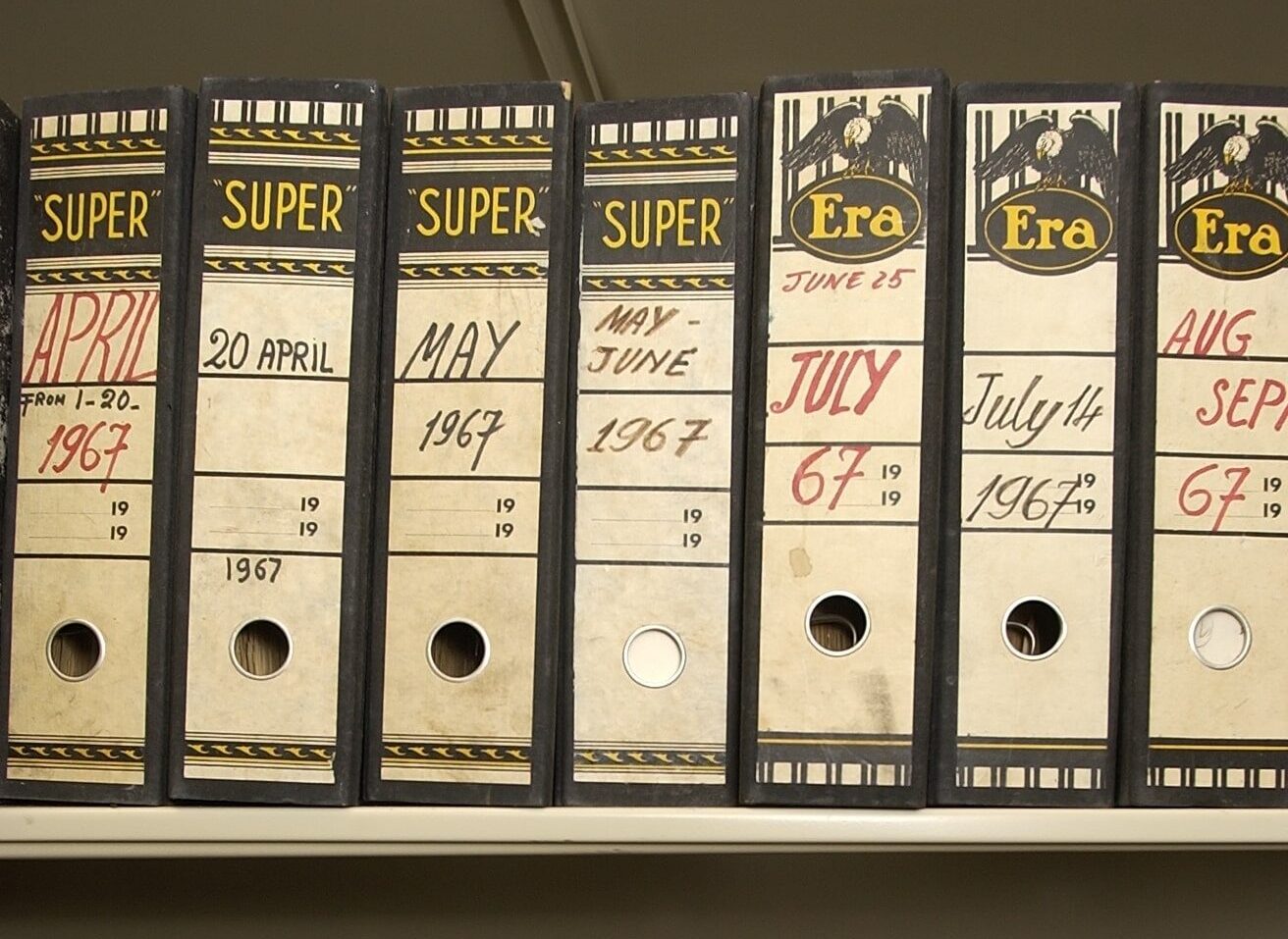

The storage rooms included one that, by all appearances in 2003, had not been entered for years. When AP’s facilities manager unlocked it for Komor and shone a flashlight inside, 50 filing cabinets came into view. Inside were the administrative and editorial correspondence of AP general managers from 1897 to 1967. Clearly someone — or some series of people — had been saving high-level documents, “but there wasn’t anybody left in 2003 that remembered that that room was there,” Komor said.

The contents of those file cabinets, which Komor named the “General Files” (after the General Office letterhead on the documents), filled nearly 400 storage boxes. As Komor sorted through them, she created a numbering system (AP 01 to AP 41) corresponding to AP’s institutional structure. (For example, any documents relating to the board of directors are labeled AP 01.) Today, the archives contain more than 5000 linear feet of paper (Komor says some “back of the envelope math” translates that into roughly 10.3 million pages). There are another 12 terabytes of digital storage (newer materials are maintained with Preservica, a digital preservation system), close to 1,000 books, and 331 artifacts — including several generations of cameras, teletype machines, and computers, as well as the Olympia portable typewriter used by Pulitzer Prize winner Peter Arnett during his years of covering Vietnam for AP.

The AP archives have continued to grow, expanded in part by initiatives like an oral history program. When Komor was hired in 2003, the files included just a handful of interviews with AP journalists about their work — including Joe Rosenthal, the AP photographer whose photo of six Marines raising an American flag on Iwo Jima is perhaps the most iconic military image from World War II. Rosenthal’s oral history of that image is a classic story-behind-the-story account. Rosenthal wasn’t present when the Marines first planted a flag. But after learning they’d been ordered to replace it with a larger one, he prepared to capture the moment by building a makeshift platform to stand on and checking and rechecking his camera settings. The archives now house close to 300 such oral histories. More recent recordings captured the experiences of some of the nine AP photographers who covered the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Expansion has also come in the form of new document acquisitions, such as papers from descendants of 19th-century AP founder Moses Yale Beach. In cataloging the Beach papers, which were added to the archives in 2005, Komor found a memo describing how Beach — publisher of the New York Sun — got several of his competitors to pool the cost of a Pony Express rider (in lieu of the U.S. postal service) to speed transmission of news from the Mexican-American War in 1846. That memo, documenting the first act of the news cooperative that came to be known as The Associated Press, led AP to revise its history, which had long given its founding date as 1848.

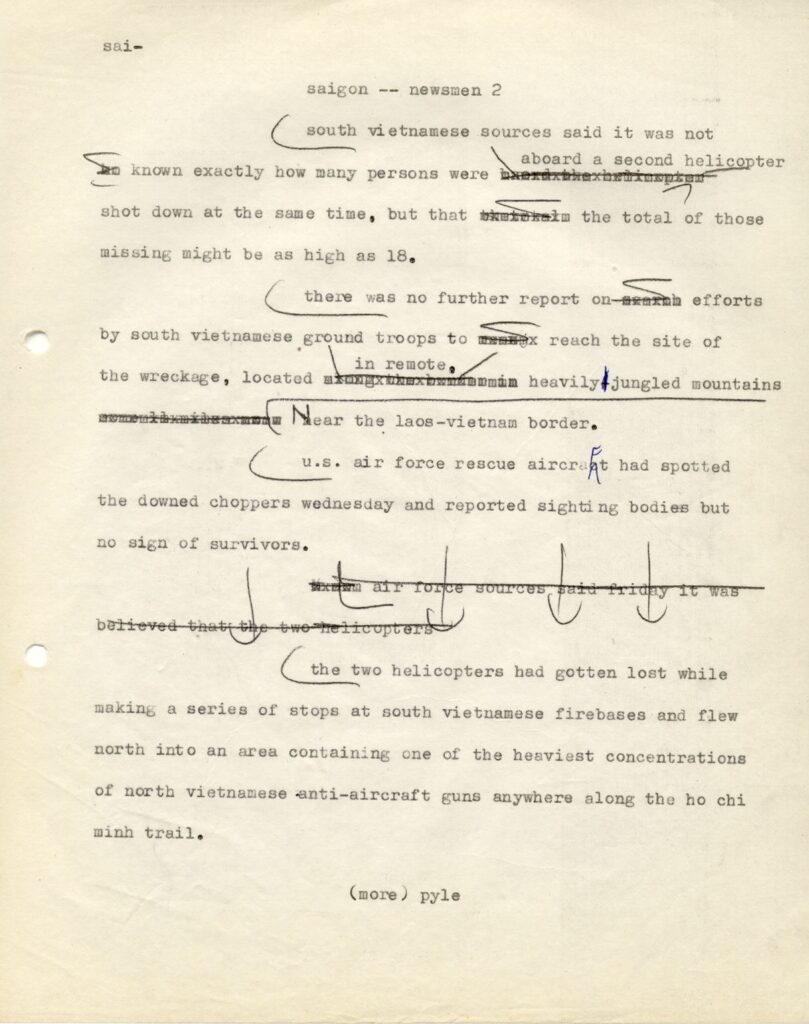

Another acquisition in 2006 put AP in possession of 136 binders holding wartime story copy and messaging between AP management and the company’s Saigon bureau during the Vietnam War. Longtime Saigon correspondent Peter Arnett was told to destroy the files before leaving

Vietnam.

Instead, he shipped them to the U.S., where, for 33 years, he personally took charge of storing them (he also used them to research his 1995 memoir) until Komor persuaded him they would be safely preserved in the new archives.

Relations between the U.S. government and the press in Vietnam were often extremely tense, as when AP’s Malcolm Browne wrote about “the war behind the war” in October 1962, exposing covert U.S. actions. (Browne compared the early U.S. military effort there to an iceberg, because “only a part of it shows,” until, for example, “a Vietnamese air force fighter plane crashes, and it is learned that the lone occupant was an American.”) The archived Vietnam files contain a letter then-general manager Wes Gallagher wrote to Browne the following month, reassuring him that government complaints about the story were just one of the “hazards of the trade.” “The only solution,” Gallagher wrote, “is to avoid allowing disputes to get personal on the local level and try your darndest to get everything out that you can.”

While other major news organizations have taken some steps to preserve their records, usually by donating them to libraries, several journalism historians who have used the AP’s corporate archives describe the company’s approach as singular. “They have made sure that they have an in-house expert [Komor], who has such a high level of understanding of their materials and the history of the organization,” said Erin Coyle, associate professor of journalism at Temple University.

“We know in journalism that we don’t throw around the word unique because it means one of a kind,” said Gwyneth Mellinger, professor of telecommunications at James Madison University, whose forthcoming book on journalism and civil rights explores the pressure southern editors put on AP in the 1940s and 1950s to use the word “negro” to identify any Black person in their copy. The AP archives provided Mellinger with an abundance of evidence. “In this particular case, that archive is probably unique,” she said.

When Tom Curley was asked to contribute to the introduction of a memoir written by Ed Kennedy, the reporter fired for his 1945 story on the end of war in Europe, he turned to original documents to explore the story behind Kennedy’s departure from AP. In the memoir, which Kennedy’s daughter had edited for publication in 2012, Kennedy argued that the military’s embargo amounted to censorship. The news was momentous, and once he confirmed that German media had already reported it, Kennedy said, he felt no obligation to honor the Allied military embargo.

While the public celebrated the news of peace in Europe, AP newspaper clients and their correspondents who had observed the embargo were infuriated that Kennedy had scooped them. AP board president Robert McLean even issued a public statement saying AP “profoundly regrets” reporting the news of Germany’s surrender without having proper military authorization to do so.

With Komor’s help in the AP Corporate Archives, Curley found private exchanges between McLean and general manager Kent Cooper, showing that Cooper initially supported Kennedy but appeared to be worn down by the journalism community’s fury and by McLean’s very public repudiation of Kennedy’s action. Two weeks after Kennedy broke the surrender news, Cooper wrote to McLean: “The writers and reporters [of AP] do not work directly for the readers but are instruments of a very much larger all-inclusive entity, which is called The Associated Press, which has an obligation to the newspapers in their service to the public.” In other words, Cooper seemed to be reversing course and telling his board president that the public’s interest in knowing the European war was over was subordinate to the interests of the infuriated AP member newspapers whose reporters Kennedy had scooped. Cooper quietly arranged Kennedy’s termination from AP.

Sixty-seven years later, Curley — satisfied from the archives research that “he [Kennedy] did everything right” — issued his own public statement repudiating Cooper and McLean. The firing of Kennedy was “a terrible day for the AP,” he said in 2012, in apologizing for the action of his AP predecessor. “Once the war is over, you can't hold back information like that. The world needed to know,” Curley wrote.