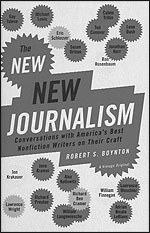

The world of letters struggles to this day to figure out how precisely to describe the revolution in nonfiction writing that appears to have begun in 1946 when John Hersey’s “Hiroshima” was published in its entirety in one issue of The New Yorker. How is it best to refer to this genre of writing—the nonfiction novel, creative nonfiction, the literature of fact, narrative journalism, new journalism, new old journalism? Now, courtesy of Robert S. Boynton, comes another label, the “new new journalism.”

In his useful guidebook, which should have a long life in classrooms as well as on the desks of reporters aspiring to do this kind of work, Boynton focuses on the writing of 16 men and three women. They differ from Tom Wolfe’s new journalists, who inhabited the first wave of innovators, whom Boynton describes as expanding “journalism’s literary scope by placing the author at the center of the story, channeling a character’s thoughts, using nonstandard punctuation, and exploding traditional narrative forms.”

As Boynton sees it, Wolfe’s heirs, whose major work appeared well after the 1960’s ended, built on those innovations, then raised the stakes—“changing the way one gets the story” by practicing immersion journalism on a grand scale. Boynton cites Ted Conover, who worked as a prison guard for “Newjack” and lived as a hobo for “Rolling Nowhere.” For many of these writers, deadlines exist as theoretical concepts: They put huge swathes of time on their side. Boynton cites several examples of writers who immersed themselves for quite some time in the lives of their subjects:

These long commitments to one’s subject are the opposite of the slapdash hit-and-run aspect of parachute journalism. The new new journalism is the literature of subcultures and the literature of the every day, as well as being the literature of the long haul.

Glimpses of Technique

The format Boynton selects to share his ideas is simple and straightforward. He frames each author’s work with an introduction that includes biographical material and a kind of critical bibliography. Then the thoughts of each subject are captured in a series of question and answers. The inspiration for the volume came from the classes in magazine journalism that Boynton teaches at New York University; the insights offered by these writers to his students provided the spine for his subsequent interviews.

Because the book’s structure has the casual back-and-forth quality of real conversations, repetitions do creep into the text, but there are plenty of payoffs when the writers take over the podium, including some small telling moments of vanity, as well as some inspiring words about how they do what they do (or sometimes don’t do).

Through Boynton’s lens, we learn a lot of details about the work habits of these writers, perhaps more than is really helpful: What does another writer learn from knowing that Conover does not need a room with a view and wrote one book in the upstairs room of a neighbor’s garage facing a blank wall? Are we enriched by finding out that Harr gets upset if he has to go out to a dinner party in the middle of the week, while Gay Talese finishes his work day at eight in the evening and then goes out? (“I like to go out. Every night. I love restaurants. Not necessarily good restaurants, but any kind of restaurant,” Talese says.) Does it matter that Jane Kramer wakes up at 7:30 each morning and needs a lot of juice and coffee and does a crossword puzzle before she can settle in? At any rate, Ron Rosenbaum beats her in the early-bird game: “I wake up at four a.m., make some strong coffee—Ethiopian lately.”

The book is marred by a few flaws—which could have been fixed by some basic fact-checking. When Harr laces into Joe McGinniss for betraying his main character, Jeffrey McDonald, in “Blind Faith,” he is clearly alluding to another McGinniss’ book, “Fatal Vision.” Boynton uses the name “Michael” when referencing Mikhail Gilmore. And it seems curious for him to tell us that Calvin Trillin’s wife, Alice, died in late 2001, when her death had the coincidental poignancy of occurring in New York City on September 11th.

In his introduction Boynton posits that there is something deeply American about this narrative art form: We are a practical people who like facts, yet we are a polyglot nation with an instinctive understanding that there is more than just one narrative line to our shared history. That said, most of Boynton’s featured writers are male and are Caucasian. While no one would deny them the breadth of their commitment nor the worthiness of their contributions, one is left to wonder how long it will take a more variegated chorus to enter the “canon” and be routinely included in volumes of this sort.

Madeleine Blais, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is professor of journalism at the University of Massachusetts and the author of “In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle.”

In his useful guidebook, which should have a long life in classrooms as well as on the desks of reporters aspiring to do this kind of work, Boynton focuses on the writing of 16 men and three women. They differ from Tom Wolfe’s new journalists, who inhabited the first wave of innovators, whom Boynton describes as expanding “journalism’s literary scope by placing the author at the center of the story, channeling a character’s thoughts, using nonstandard punctuation, and exploding traditional narrative forms.”

As Boynton sees it, Wolfe’s heirs, whose major work appeared well after the 1960’s ended, built on those innovations, then raised the stakes—“changing the way one gets the story” by practicing immersion journalism on a grand scale. Boynton cites Ted Conover, who worked as a prison guard for “Newjack” and lived as a hobo for “Rolling Nowhere.” For many of these writers, deadlines exist as theoretical concepts: They put huge swathes of time on their side. Boynton cites several examples of writers who immersed themselves for quite some time in the lives of their subjects:

- Leon Dash spent five years following various characters who surrounded Rosa Lee, a drug-addicted grandmother he met who had been arrested for selling drugs to feed two of her grandchildren.

- Adrian Nicole LeBlanc devoted nearly 10 years to living among the young people and their children whose connected lives comprise her book, “Random Family.”

- Jonathan Harr spent about eight years working on “A Civil Action.”

These long commitments to one’s subject are the opposite of the slapdash hit-and-run aspect of parachute journalism. The new new journalism is the literature of subcultures and the literature of the every day, as well as being the literature of the long haul.

Glimpses of Technique

The format Boynton selects to share his ideas is simple and straightforward. He frames each author’s work with an introduction that includes biographical material and a kind of critical bibliography. Then the thoughts of each subject are captured in a series of question and answers. The inspiration for the volume came from the classes in magazine journalism that Boynton teaches at New York University; the insights offered by these writers to his students provided the spine for his subsequent interviews.

Because the book’s structure has the casual back-and-forth quality of real conversations, repetitions do creep into the text, but there are plenty of payoffs when the writers take over the podium, including some small telling moments of vanity, as well as some inspiring words about how they do what they do (or sometimes don’t do).

- Ted Conover on bad ideas: “Well, in the early 1990’s, when everyone was getting online, I thought of doing a travel book about the Internet. My cyber-travel would itself structure the narrative. At the time it sounded good, but eventually I concluded it was more interesting as a sentence than as a book.”

- Leon Dash shares his response to Rosa Lee after she’d asked him about whether she should stop teaching her daughter to shoplift. His answer is not a simple one, veering into the murky ethics of the relationship between author and subject.

- Jonathan Harr describes his disappointment when he was preparing do a book on a dig at the Turkish-Syrian border, but backed off when the lead archeologist demanded a percentage of whatever he earned from the book.

- Alex Kotlowitz explains why he eschews tape recorders, other than for interviews with public figures who he thinks could become argumentative, while Adrian Nicole LeBlanc likes to use them. As a way to avoid the awkwardness the recorders sometimes inspire, from time to time she hands hers over to her subjects so that they can control the “on” button.

- Jon Krakauer shares his secret for outlining complicated subjects, which he compares to rock climbing: “When you embark on a really big climb, like, say, the Salathé wall of El Capitan, which rises three thousand vertical feet from the floor of the Yosemite Valley, the enormity of the undertaking can be paralyzing. So a climber breaks down the ascent into rope-lengths, or pitches. If you can think of the climb as a series of 20 or 30 pitches, and focus on each of these pitches to the exclusion of the scary pitches that lie above, climbing El Cap suddenly doesn’t seem to be such an intimidating project.”

- Jane Kramer speaks to her special method for interviewing peripheral characters in which she asks each of them the same questions. “It’s a kind of Rashomon tactic. I am interested in what emerges about each person in terms of what he or she adds or subtracts from that basic narrative.”

- Susan Orlean, in response to the question “How do you know when the interviewing phase is done?,” provides the brilliantly succinct answer, “When my attention span becomes shorter. In the beginning of a story my learning curve is so steep that everything the person says is new and fascinating. Then it slows down naturally as I become more and more familiar with the person and his story. Finally, I feel an intuitive shift from listening to the process of writing the story in my head.”

- Calvin Trillin’s measure for what makes a good story is whether it sounds interesting, which he realizes has more to do with some internalized click than any other more objective system. He believes murders make good stories because they have a built-in plot line and, better yet, there is likely to be a court hearing with a transcript: “I used to say that I’d go anywhere there was a transcript—which isn’t quite true, but almost. My absolute favorite thing is when there is always a transcript from a defendant’s previous trial. That way I have both a transcript to read and a trial to attend.”

Through Boynton’s lens, we learn a lot of details about the work habits of these writers, perhaps more than is really helpful: What does another writer learn from knowing that Conover does not need a room with a view and wrote one book in the upstairs room of a neighbor’s garage facing a blank wall? Are we enriched by finding out that Harr gets upset if he has to go out to a dinner party in the middle of the week, while Gay Talese finishes his work day at eight in the evening and then goes out? (“I like to go out. Every night. I love restaurants. Not necessarily good restaurants, but any kind of restaurant,” Talese says.) Does it matter that Jane Kramer wakes up at 7:30 each morning and needs a lot of juice and coffee and does a crossword puzzle before she can settle in? At any rate, Ron Rosenbaum beats her in the early-bird game: “I wake up at four a.m., make some strong coffee—Ethiopian lately.”

The book is marred by a few flaws—which could have been fixed by some basic fact-checking. When Harr laces into Joe McGinniss for betraying his main character, Jeffrey McDonald, in “Blind Faith,” he is clearly alluding to another McGinniss’ book, “Fatal Vision.” Boynton uses the name “Michael” when referencing Mikhail Gilmore. And it seems curious for him to tell us that Calvin Trillin’s wife, Alice, died in late 2001, when her death had the coincidental poignancy of occurring in New York City on September 11th.

In his introduction Boynton posits that there is something deeply American about this narrative art form: We are a practical people who like facts, yet we are a polyglot nation with an instinctive understanding that there is more than just one narrative line to our shared history. That said, most of Boynton’s featured writers are male and are Caucasian. While no one would deny them the breadth of their commitment nor the worthiness of their contributions, one is left to wonder how long it will take a more variegated chorus to enter the “canon” and be routinely included in volumes of this sort.

Madeleine Blais, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is professor of journalism at the University of Massachusetts and the author of “In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle.”