The terrorism attacks of September 11, 2001 profoundly changed the rules of engagement for America’s editorial cartoonists, who directed their sense of outrage at a world that was shifting uneasily under their drawing boards, leaving them struggling to convey their reactions in a single image. In the days and weeks that followed, editorial pages were strewn with images of fiery twin towers, weeping Statues of Liberty, snarling bald eagles, and resolute Uncle Sams rolling up their sleeves to march into hell for a heavenly cause.

Amid the chaos of the first great crisis of the 21st century, most Americans, including cartoonists, believed it was inappropriate, even unpatriotic, to criticize President George W. Bush. Garry Trudeau, who draws “Doonesbury,” canceled a series of strips critical of the President. Syndicated cartoonist Pat Oli-phant, who has a well-deserved reputation for merciless satire, said cartoonists had to support the administration—at least for the time being.

Soon after the terrorist attacks, however, a few cartoonists returned to social satire, believing—contrary to many of their colleagues and read-ers—that giving our leaders a free pass during times of crisis undermines our democracy. Trudeau ended his armistice with a strip pointing out that President Bush and his administration were using the tragedy to move their conservative agenda forward. One drawing shows Bush’s chief political aide Karl Rove telling the President that several of the controversial items on his political agenda were “justified by the war against terrorism!” Bush replies: “Wow … what a coincidence … thanks evildoers!”

The Bush administration insisted it needed to increase its authority to win the war on terrorism. Congress quickly passed the USA Patriot Act, which provided the Justice Department and other agencies wide latitude to disregard the Bill of Rights for purposes of surveillance and law enforcement.

RELATED ARTICLE

"The Red, White and Blue Palette"

- Excerpts from a speech by Ann TelnaesStill, most editorial cartoonists condemned America’s enemies but refrained from questioning the Bush administration, either willingly supporting the President or fearful of incurring the wrath of their editors or readers. Editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes scolded those in her profession for being government cheerleaders. She’s right. Cartoonists should not be government propagandists. As social critics, cartoonists should keep a vigilant eye on the democracy and those threatening it, whether the threats come from outside or inside the country.

Cartoonists and Patriotism

But what happens when First Amendment theory clashes with more than 3,000 people dying in acts of atrocious inhumanity followed by the reality of a war against an unseen enemy? In this fog of war, those cartoonists who criticized the administration had their patriotism questioned, their lives threatened, and their livelihoods jeopardized.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Understanding the Value of the Local Connection"

- Scott StantisUsing shameless nationalistic blather, then White House spokesman Ari Fleischer condemned a cartoon critical of Bush that appeared in a small New Hampshire newspaper, resulting in the firing of the newspaper’s editor and the vilification of the cartoonist. The New York Times dropped Ted Rall from its Web site because of his harsh criticism of the Bush administration. Scott Stantis, then the president of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists, said that cartoonists found themselves “under particular scrutiny” after September 11th. “A number of cartoonists have heard ‘You’re a traitor’ anytime they question the President,’” Stantis said.

But nothing is more patriotic than social criticism. Editorial cartoons are as irreverent as the Boston Tea Party and as American as the U.S. Constitution. The First Amendment doesn’t exist so we can praise our public officials; it exists so we can criticize them. Newspapers who give their cartoonists the freedom to express their views, as free as possible from editorial restraint, reinforce the message that an uninhibited exchange of opinions not only strengthens but also maintains our democracy; in fact, it is necessary for a democracy.

The sad state of editorial cartooning is a result of the current economics of the newspaper industry and of editors who have little appreciation for political satire. As the newspaper industry has declined in both readership and influence so, too, has journalistic decision-making by editors, many of whom opt for publishing generic syndicated cartoons over provocative, staff-drawn cartoons. They do this because the cartoons are cheaper, and they generate fewer phone calls and e-mails from readers. Too many editors want editorial cartoons to be objective, like news stories. But that’s not what editorial cartoons are supposed to do.

The Value of Editorial Cartoons

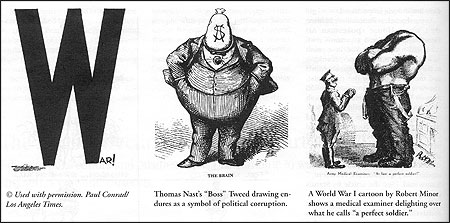

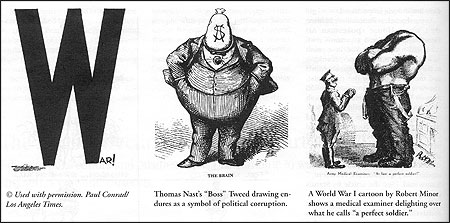

When editorial cartoons are at their best, they’re like switchblades—simple and to the point. They cut deeply and leave a scar. No editorial on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration is as memorable as David Levine’s drawing of LBJ lifting up his shirt to reveal his gall bladder scar in the shape of Vietnam. Herbert Block, or Herblock as he signed his cartoons, captured the anti-Communist hysteria of the Red Scare by creating the word “McCarthyism.” Later, Herblock’s portrayal of Richard Nixon climbing out of a sewer made such an impression on Nixon that he later told an adviser, “I have to erase the Herblock image.” Robert Minor’s searing World War I cartoon of a medical examiner salivating over a giant headless soldier and gushing, “At last a perfect soldier!” is a timeless indictment of war. And Thomas Nast’s drawing of “Boss” Tweed as a bag of money remains an enduring symbol of political corruption.

Newspapers must believe that editorial cartoons have some value, or else why would they run them every day on their editorial and op-ed pages? Their readership studies tell them that editorial cartoons bring readers to the editorial page. Bruce Dold, the editorial page editor of the Chicago Tribune, says that the “cartoon is the best read thing on the editorial page. People think it’s quick, it’s funny, and often it’s insightful. It’s often the only laugh on a page of very serious public policy.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Freedom of Speech and the Editorial Cartoon"

- Doug MarletteDold makes a strong case for a newspaper having an editorial cartoonist. Yet the Tribune has not had a cartoonist since the death of Jeff MacNelly in 2000. Dold blames economics. But after four years, this is a tired explanation. Other explanations for why newspapers don’t have cartoonists are weaker still. Cartoonist Doug Marlette remembers a conversation he had with former New York Times editor Max Frankel, when Marlette asked why the newspaper didn’t have a staff cartoonist. “The problem with editorial cartoonists,” he was told, “is that you can’t edit them.” To which Marlette responded: “Why would you want to?”

Editorial cartoonists are given the Rodney Dangerfield treatment, which suggests that newspapers, unlike their readers, underestimate—and certainly underappreciate—the value of humor, satire and visual commentary. “The world likes humor but treats it patronizingly,” E.B. White wrote several decades ago. “It decorates its serious artists with laurels and its wags with Brussels sprouts. It feels that if a thing is funny it can be presumed to be something less than great because if it were great it would be wholly serious.”

Even those newspapers with staff cartoonists treat them as illustrators of their editorial line. In fact, newspaper editors generally give writers of letters to the editor more freedom than their editorial cartoonists. Unlike letters to the editor, editorial cartoons generally are not allowed to contradict the newspaper’s editorial policy. Rare is the editor who sees his cartoonist as an independent contractor. The Los Angeles Times respected Paul Conrad enough to do that; not coincidentally, Conrad, at his best, represented the best of editorial cartooning. He took on the high and mighty without fear or favor and was not afraid to turn a mirror on us and reveal us not as we want to be but as we are. On the contrary, Michael Ramirez, Conrad’s successor at the Times, often acts as an apologist of the Bush administration.

Editorial cartoonists today are less watchdogs of the public trust than lapdogs of the newspaper industry’s corporate establishment. This has been particularly true during the Bush administration’s war on terrorism when newspapers have abandoned their responsibilities to question the government. Much of the most provocative criticism of the Bush administration has been drawn by a relatively small number of syndicated cartoonists—such as Trudeau, Oliphant, Rall, Telnaes, and Jeff Danziger—who are less affected by newsroom pressures.

But syndication produces its own problems. One measure of success in cartooning is to be syndicated. If a cartoonist yearns to have his drawings appear in more and more newspapers, which translates into more money and more visibility, he or she tries to appeal to as many readers as possible. For too many cartoonists, this produces work that is long on punch line but short on punch; as a result, we get too many drawings about Martha Stewart and not enough about U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft.

Cartoonists are right to blame editors and publishers for not taking their art seriously. But why should editors do this when cartoonists don’t take themselves seriously? Too much of editorial cartooning today is instantly forgettable. Too many cartoonists rely on their first drafts, which explains why so many cartoons are superficial or look like one another. They’ve abandoned the sense of righteous indignation that inspires the profession’s best instincts, or its “killer angels,” as Marlette put it. Marlette was once asked what makes a good cartoon, and he answered, “Can you remember it? Did it tattoo your soul?”

Between 80 and 90 editorial cartoonists presently work in full-time staff positions for daily newspapers. Twenty-five years ago, that number was perhaps twice that size. And cartoonists with jobs feel pressured to obey their editors or risk losing their job. Earlier this year, John Sherffius of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch quit rather than work within the onerous dictates of an editor who insisted that he include criticism of Democrats in cartoons that criticized the Bush administration.

Newspaper editors need to quit acting like government bureaucrats and corporate accountants. If they begin acting like guardians of the public

trust, as they’re intended to do, they might find that their editorial pages give readers something to look forward to in the morning. They can do this by hiring editorial cartoonists and letting them do what editorial cartoonists are supposed to do: afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

By preserving editorial cartooning, newspapers perhaps can save themselves. The newspaper industry, with its best days behind it, can learn from the past and do what newspapers did 100 years ago when, as one historian put it, every self-respecting editor had a cartoonist on staff and often put his work on Page One. This increased not just the newspaper’s circulation, but it also increased political activism. This could happen and, in doing so, it would serve as a daily remainder to its readers of the importance of social criticism in a democracy.

Chris Lamb is an associate professor of communication at the College of Charleston in South Carolina and author of “Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons in the United States,” published by Columbia University Press in 2004.

Amid the chaos of the first great crisis of the 21st century, most Americans, including cartoonists, believed it was inappropriate, even unpatriotic, to criticize President George W. Bush. Garry Trudeau, who draws “Doonesbury,” canceled a series of strips critical of the President. Syndicated cartoonist Pat Oli-phant, who has a well-deserved reputation for merciless satire, said cartoonists had to support the administration—at least for the time being.

Soon after the terrorist attacks, however, a few cartoonists returned to social satire, believing—contrary to many of their colleagues and read-ers—that giving our leaders a free pass during times of crisis undermines our democracy. Trudeau ended his armistice with a strip pointing out that President Bush and his administration were using the tragedy to move their conservative agenda forward. One drawing shows Bush’s chief political aide Karl Rove telling the President that several of the controversial items on his political agenda were “justified by the war against terrorism!” Bush replies: “Wow … what a coincidence … thanks evildoers!”

The Bush administration insisted it needed to increase its authority to win the war on terrorism. Congress quickly passed the USA Patriot Act, which provided the Justice Department and other agencies wide latitude to disregard the Bill of Rights for purposes of surveillance and law enforcement.

RELATED ARTICLE

"The Red, White and Blue Palette"

- Excerpts from a speech by Ann TelnaesStill, most editorial cartoonists condemned America’s enemies but refrained from questioning the Bush administration, either willingly supporting the President or fearful of incurring the wrath of their editors or readers. Editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes scolded those in her profession for being government cheerleaders. She’s right. Cartoonists should not be government propagandists. As social critics, cartoonists should keep a vigilant eye on the democracy and those threatening it, whether the threats come from outside or inside the country.

Cartoonists and Patriotism

But what happens when First Amendment theory clashes with more than 3,000 people dying in acts of atrocious inhumanity followed by the reality of a war against an unseen enemy? In this fog of war, those cartoonists who criticized the administration had their patriotism questioned, their lives threatened, and their livelihoods jeopardized.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Understanding the Value of the Local Connection"

- Scott StantisUsing shameless nationalistic blather, then White House spokesman Ari Fleischer condemned a cartoon critical of Bush that appeared in a small New Hampshire newspaper, resulting in the firing of the newspaper’s editor and the vilification of the cartoonist. The New York Times dropped Ted Rall from its Web site because of his harsh criticism of the Bush administration. Scott Stantis, then the president of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists, said that cartoonists found themselves “under particular scrutiny” after September 11th. “A number of cartoonists have heard ‘You’re a traitor’ anytime they question the President,’” Stantis said.

But nothing is more patriotic than social criticism. Editorial cartoons are as irreverent as the Boston Tea Party and as American as the U.S. Constitution. The First Amendment doesn’t exist so we can praise our public officials; it exists so we can criticize them. Newspapers who give their cartoonists the freedom to express their views, as free as possible from editorial restraint, reinforce the message that an uninhibited exchange of opinions not only strengthens but also maintains our democracy; in fact, it is necessary for a democracy.

The sad state of editorial cartooning is a result of the current economics of the newspaper industry and of editors who have little appreciation for political satire. As the newspaper industry has declined in both readership and influence so, too, has journalistic decision-making by editors, many of whom opt for publishing generic syndicated cartoons over provocative, staff-drawn cartoons. They do this because the cartoons are cheaper, and they generate fewer phone calls and e-mails from readers. Too many editors want editorial cartoons to be objective, like news stories. But that’s not what editorial cartoons are supposed to do.

The Value of Editorial Cartoons

When editorial cartoons are at their best, they’re like switchblades—simple and to the point. They cut deeply and leave a scar. No editorial on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration is as memorable as David Levine’s drawing of LBJ lifting up his shirt to reveal his gall bladder scar in the shape of Vietnam. Herbert Block, or Herblock as he signed his cartoons, captured the anti-Communist hysteria of the Red Scare by creating the word “McCarthyism.” Later, Herblock’s portrayal of Richard Nixon climbing out of a sewer made such an impression on Nixon that he later told an adviser, “I have to erase the Herblock image.” Robert Minor’s searing World War I cartoon of a medical examiner salivating over a giant headless soldier and gushing, “At last a perfect soldier!” is a timeless indictment of war. And Thomas Nast’s drawing of “Boss” Tweed as a bag of money remains an enduring symbol of political corruption.

Newspapers must believe that editorial cartoons have some value, or else why would they run them every day on their editorial and op-ed pages? Their readership studies tell them that editorial cartoons bring readers to the editorial page. Bruce Dold, the editorial page editor of the Chicago Tribune, says that the “cartoon is the best read thing on the editorial page. People think it’s quick, it’s funny, and often it’s insightful. It’s often the only laugh on a page of very serious public policy.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Freedom of Speech and the Editorial Cartoon"

- Doug MarletteDold makes a strong case for a newspaper having an editorial cartoonist. Yet the Tribune has not had a cartoonist since the death of Jeff MacNelly in 2000. Dold blames economics. But after four years, this is a tired explanation. Other explanations for why newspapers don’t have cartoonists are weaker still. Cartoonist Doug Marlette remembers a conversation he had with former New York Times editor Max Frankel, when Marlette asked why the newspaper didn’t have a staff cartoonist. “The problem with editorial cartoonists,” he was told, “is that you can’t edit them.” To which Marlette responded: “Why would you want to?”

Editorial cartoonists are given the Rodney Dangerfield treatment, which suggests that newspapers, unlike their readers, underestimate—and certainly underappreciate—the value of humor, satire and visual commentary. “The world likes humor but treats it patronizingly,” E.B. White wrote several decades ago. “It decorates its serious artists with laurels and its wags with Brussels sprouts. It feels that if a thing is funny it can be presumed to be something less than great because if it were great it would be wholly serious.”

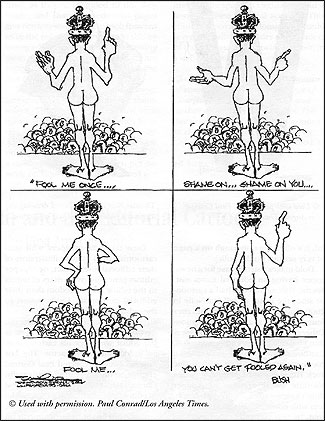

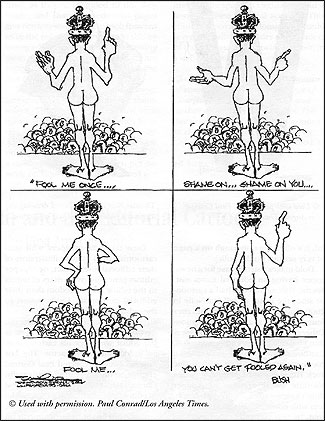

Even those newspapers with staff cartoonists treat them as illustrators of their editorial line. In fact, newspaper editors generally give writers of letters to the editor more freedom than their editorial cartoonists. Unlike letters to the editor, editorial cartoons generally are not allowed to contradict the newspaper’s editorial policy. Rare is the editor who sees his cartoonist as an independent contractor. The Los Angeles Times respected Paul Conrad enough to do that; not coincidentally, Conrad, at his best, represented the best of editorial cartooning. He took on the high and mighty without fear or favor and was not afraid to turn a mirror on us and reveal us not as we want to be but as we are. On the contrary, Michael Ramirez, Conrad’s successor at the Times, often acts as an apologist of the Bush administration.

Editorial cartoonists today are less watchdogs of the public trust than lapdogs of the newspaper industry’s corporate establishment. This has been particularly true during the Bush administration’s war on terrorism when newspapers have abandoned their responsibilities to question the government. Much of the most provocative criticism of the Bush administration has been drawn by a relatively small number of syndicated cartoonists—such as Trudeau, Oliphant, Rall, Telnaes, and Jeff Danziger—who are less affected by newsroom pressures.

But syndication produces its own problems. One measure of success in cartooning is to be syndicated. If a cartoonist yearns to have his drawings appear in more and more newspapers, which translates into more money and more visibility, he or she tries to appeal to as many readers as possible. For too many cartoonists, this produces work that is long on punch line but short on punch; as a result, we get too many drawings about Martha Stewart and not enough about U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft.

Cartoonists are right to blame editors and publishers for not taking their art seriously. But why should editors do this when cartoonists don’t take themselves seriously? Too much of editorial cartooning today is instantly forgettable. Too many cartoonists rely on their first drafts, which explains why so many cartoons are superficial or look like one another. They’ve abandoned the sense of righteous indignation that inspires the profession’s best instincts, or its “killer angels,” as Marlette put it. Marlette was once asked what makes a good cartoon, and he answered, “Can you remember it? Did it tattoo your soul?”

Between 80 and 90 editorial cartoonists presently work in full-time staff positions for daily newspapers. Twenty-five years ago, that number was perhaps twice that size. And cartoonists with jobs feel pressured to obey their editors or risk losing their job. Earlier this year, John Sherffius of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch quit rather than work within the onerous dictates of an editor who insisted that he include criticism of Democrats in cartoons that criticized the Bush administration.

Newspaper editors need to quit acting like government bureaucrats and corporate accountants. If they begin acting like guardians of the public

trust, as they’re intended to do, they might find that their editorial pages give readers something to look forward to in the morning. They can do this by hiring editorial cartoonists and letting them do what editorial cartoonists are supposed to do: afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

By preserving editorial cartooning, newspapers perhaps can save themselves. The newspaper industry, with its best days behind it, can learn from the past and do what newspapers did 100 years ago when, as one historian put it, every self-respecting editor had a cartoonist on staff and often put his work on Page One. This increased not just the newspaper’s circulation, but it also increased political activism. This could happen and, in doing so, it would serve as a daily remainder to its readers of the importance of social criticism in a democracy.

Chris Lamb is an associate professor of communication at the College of Charleston in South Carolina and author of “Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons in the United States,” published by Columbia University Press in 2004.