Day at our house in the northeastern part of Bangladesh would break with a rally of sounds.

First, it was Azan, the call to prayer from the mosque. Then came my dad’s recitation from the Holy Quran, tinkling sounds from the kitchen, some music on the radio, and my mother humming along with it. I resisted all those sounds, pressing the pillow over my ears, reluctant to wake up for school. When the signature tune of BBC Bangla came on, though, I knew that was the last call for me to get out of bed.

In Bangladesh in the mid-80s, children like me from middle-class and lower middle-class families used to listen to bedtime stories and lullabies from our mothers. The stories were essentially fairy tales from Bengal or the Soviet Union; very few of us heard Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales or fairy tales from Japan and Africa. My siblings and I could not always align our lives with the fairy tale characters with which we grew up. There was always some tension, a distinct kind that hovers over every refugee family.

My parents left their home in India after the great partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 and moved to the eastern part of Bengal, now Bangladesh, which became independent in 1971. For the rest of their lives, my parents found it hard to make ends meet. They wanted us to leave a mark on the world. So, they introduced us to the Abrahamic prophets, the gods and goddesses from the Indian epic Ramayana, the speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Mahatma Gandhi, and cultural figures like Michael Jackson and Muhammad Ali.

We would read the newspaper aloud as a family. And as a teenager, I decided to become a journalist like BBC correspondent Lyse Doucet, whom I greatly admired.

Newspapers and radio played a defiant role in Bangladesh’s liberation war. But just four years after independence, the government banned publication of all newspapers except four, which were controlled by the state. Censorship, the murder and persecution of reporters, and poor salaries were the norm.

The situation hasn’t changed much. According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Bangladesh ranked 162 out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index. Reporters are routinely harassed; perpetrators enjoy impunity and often receive encouragement from the powerful. In 2020, journalist Golam Sarwar was sent to a secret detention center for writing a story against land grabbers. The same year kidnappers took photojournalist Shafiqul Islam Kajal in front of his office, and he remained missing for 53 days until he was released. Police arrested journalist Rozina Islam for allegedly stealing documents and sent her to prison.

In addition, newsrooms are still dominated by men. Only a handful of women are in leadership positions, and in most cases, they don’t get a chance to advance in their careers.

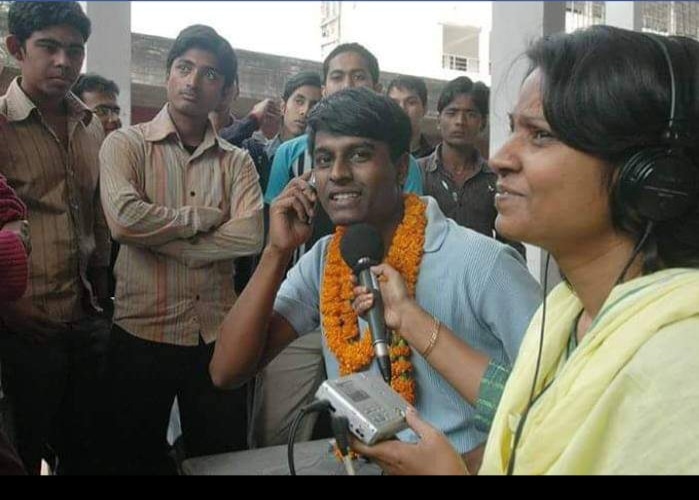

I started my career at bdnews24, Bangladesh’s first online newspaper, then moved on to stints at The Daily Star and BBC Bangla, before joining Prothom Alo, the largest Bengali daily. Over the past 17 years, I’ve witnessed and covered major events that shaped the history of Bangladesh — the 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza that claimed over one thousand lives, cyclones and floods, ISIS attacks, and state-sponsored brutality against dissidents. Then came the pandemic. The media industry in Bangladesh was already going through a rough patch and, like in so many newsrooms around the world, Covid-19 just made things worse. During the same period, my phone was hacked, and a private conversation was released that caused me public embarrassment and tensions in my newsroom.

Some advised me to quit journalism. But how could I do that? I carry the tears of victims — their anguish, anger, despair, and disbelief. Storytelling is the only tool to relieve this burden.

One of the poems I read as a child was Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The ancient mariner killed an albatross — a good omen at sea — on a whim, and his ship immediately became becalmed. Angry sailors hung the dead albatross around the ancient mariner’s neck. And with the dead albatross hanging from his neck, the ancient mariner watched his fellow sailors dying one by one.

During this difficult period, I felt like the ancient mariner. It felt like watching the end of my career. But the Nieman fellowship has put fresh wind in my sails. The space for independent journalism in Bangladesh is narrow, and any new outlet requires government approval. But after the fellowship, I will return to my readers at Prothom Alo, focusing my stories on human rights violations, stories that otherwise might go untold. I still have many stories to tell. As Coleridge wrote, “Till my ghastly tale is told, this heart within me burns.”