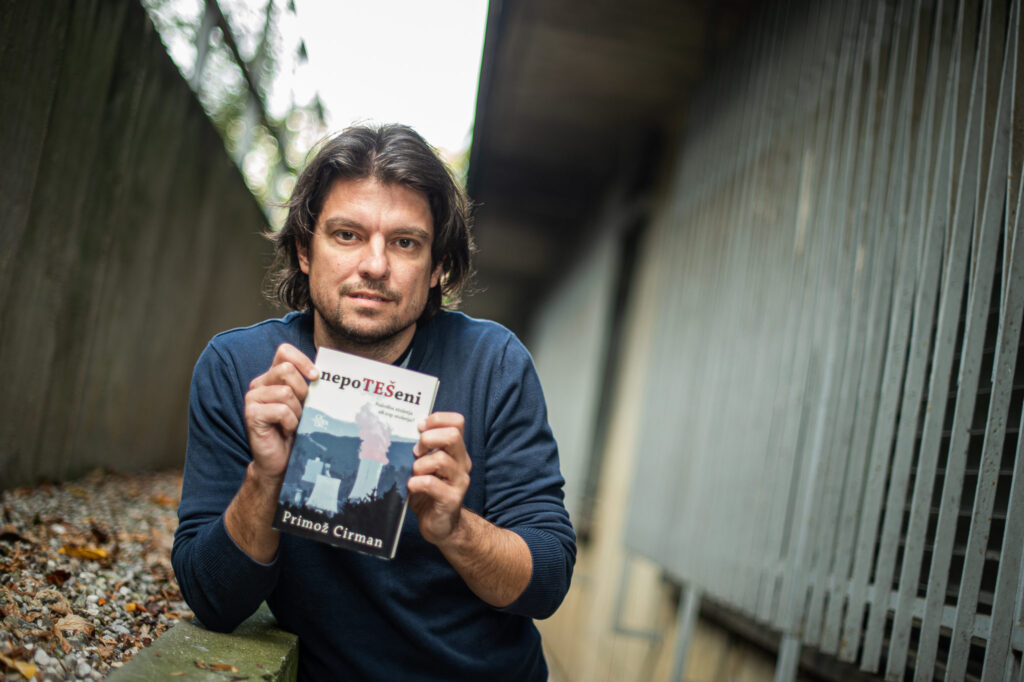

Primož Cirman started receiving orange, business-card-sized slips of paper in his Celje, Slovenia, mailbox in June 2020. They haven’t stopped coming.

Each card is a notice that he has a piece of certified mail waiting for him at the post office near his house. At first, every ten-minute walk to the post office yielded an envelope informing him of a new defamation lawsuit against him. “In my post office, they were watching me strangely at first,” Cirman says. “Why does that guy keep getting court orders? I said to them, ‘I didn’t kill anybody. I’m just a journalist.’”

More recently, the cards alert him to updates on his cases. Post office officials have set aside a space on a shelf for his legal documents.

Cirman, editor of Necenzurirano, a Slovenian news organization, has been the subject of 15 defamation lawsuits, all stemming from his reporting about Rok Snežić, an adviser to former Prime Minister Janez Janša. His colleagues Vesna Vukovic and Tomaž Modic also accrued 15 lawsuits each. Snežić “basically picked every article we ever wrote about him and filed a lawsuit — for each of us,” Cirman says. “Why? Each lawsuit needs a response from a lawyer and that costs money.”

The lawsuits Cirman and his colleagues face are often classified as SLAPPs — strategic lawsuits against public participation. The lawsuits allow people with power to intimidate and silence journalists and others through financially draining litigation and fear and uncertainty about their futures. The London-based Business & Human Rights Resource Centre tracked 355 SLAPPs worldwide between 2015 and 2021.

SLAPPs are part of a growing list of headwinds journalists face around the world. In Russia, for example, independent journalism has been all but shut down following the passage of the so-called “fake news” law that prohibits reporting on the war in Ukraine. Several other countries have introduced similar laws that can be manipulated to criminalize reporting that is unfavorable to governments in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Female journalists in Iran are being jailed at unprecedented rates — two are facing the death penalty — for covering the protests following the death of Mahsa Amini in September. Violence against journalists continues to hamper their work on a global scale, and people like Donald Trump and his followers are turning chunks of the electorate against facts and legitimate journalism.

SLAPPs are a particularly effective tool for those in power to silence cash-strapped news organizations and reporters.

Nieman Reports spoke with journalists on four continents about their experiences, with each providing lessons about using the resources available, forming international coalitions, finding support in their audiences, and fighting the harassment that often comes with SLAPP lawsuits.

Ask Your Audience for Help

Steven Gan couldn’t believe what he’d just heard.

Sitting in a mostly empty Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, courtroom during the Covid-19 pandemic in February 2021, he shifted in his seat and asked Malaysiakini co-founder Premesh Chandran if he’d correctly heard the fine the judge had just announced against their news organization.

He had.

The Federal Court had just fined the independent news outlet roughly $124,000 for five reader comments posted on its website, even though the comments were quickly removed. The comments that led to the fine were in response to a June 2020 report about the courts lifting Covid-19 restrictions. When Malaysiakini editors were notified by police about the comments, the comments were deleted within twelve minutes. Gan provided a statement to police, and the news organization banned the five commenters. Still, the government pursued contempt-of-court proceedings against Malaysiakini — a legal action that can have the same chilling effect on press freedom as more traditional SLAPP suits.

Government prosecutors sought a $50,000 fine. The judges, however, set the fine at well more than double that number. To make matters worse, Gan and his news organization had about a week to pay or Malaysiakini would cease to exist.

Gan, Chandran, some staffers, and supporters stopped at an outdoor food stand on their way back from the court to the office. They were ready for a fine, perhaps even $50,000, as the government sought. More than $100,000 to be paid in such a short time, however, was concerning. “I was expecting a hefty fine,” Gan says, “but I was stunned by that.”

They had to try to save their news outlet. Gan set the staff’s plan in motion before lunch. They posted a report about the court’s decision and a crowdfunding request. As they sat outside and ate, Gan checked his phone every few minutes. “I was constantly receiving updates from our head of finance, who was furiously checking our bank account to check how much,” Gan says. “He told me he was happy to see the amount went up every time he clicked refresh.”

They reached $50,000 before they returned to the office. They had more than $100,000 before the end of the day. Finally, they messaged subscribers to stop contributing. They’d surpassed the amount they needed to pay the fine in a matter of hours. “It ended up as a victory for Malaysiakini,” says Gan. “Despite the fact that we lost the court case, it was a victory because we were able to raise the money, and it shows Malaysiakini has sizable support out there.”

The audience saved the news organization. Gan emphasizes that the reader-news outlet relationship didn’t suddenly appear after the court’s decision in February 2021. Malaysiakini has a long history of engaging with its audience.

Several years earlier, when a landlord evicted the outlet from its offices, giving Malaysiakini short notice to find another location, the staff moved into a shopping mall. Reporters and editors used a restaurant’s free Wi-Fi — and invited readers to join them. “We told our readers we’re going to be working there,” Gan recalls. “We’re going to be outside a Burger King.”

Readers came. They had coffee and tea with reporters, creating a bond. When it came time to find a permanent home for Malaysiakini, the organization sold bricks, allowing supporters to put their names into the structure of the building. They sold out.

The wall connects the newsroom and a cafeteria that is in the Malaysiakini building and is open to the public. Readers can stop by and have coffee or tea with journalists.

“Every time I feel pressured or despondent, I will go down and look at the big wall,” Gan says. “I’ll read the names. One by one. I go down and read the names and get inspired again and go back up and continue my work.”

While the relationship between Malaysiakini and its readers helped save the news outlet, Gan emphasizes the long-term goal must be reforming Malaysia’s press-freedom-limiting laws and judiciary.

Gan lists three laws, among at least a dozen, that limit press freedom in Malaysia. He highlights the Official Secrets Act, which prohibits certain types of information gathering, the Printing Presses and Publications Act, which requires printers to attain a license from the government, and the Communication and Multimedia Act. The CMA, which was the law under which Malaysiakini was charged, makes media outlets criminally liable for content that is published by users, such as reader comments, on their websites. Publishers who violate the law can face fines as well as up to five years in prison.

He also emphasizes Malaysian courts need judges who respect the value of the press. “We have to campaign for law reforms,” Gan says. “It will take time. In the meantime, we’re going to face these problems.”

Get Legal Advice

The Dallas Express was one of the largest and oldest Black-run newspapers in the South — until it closed in 1970. When the Express reappeared in 2021, Dallas media took notice. Its new owner, Monty Bennett, a conservative business executive and Trump donor, raised eyebrows.

The new version of the Express, which labels itself “the People’s Paper,” was created to “fill a void in our Metroplex communities for fact-based, non-opinion news,” according to the site’s mission statement. But, before Bennett launched the new site, both The New York Times and D Magazine — a monthly publication covering Dallas-Fort Worth — had written about Bennett’s connection to pay-for-play news sites that published articles about the importance of federal stimulus to help companies struggling during the pandemic. (Bennett was a major recipient of stimulus cash, though he wound up returning the money after a public criticism.)

Steven Monacelli, a freelance journalist, reported about the Express’s new owner for the Dallas Weekly, a news outlet that focuses on Dallas’s Black communities. Citing D Magazine and The New York Times, Monacelli referred to Bennett’s Express as “pink slime” and a “right wing propaganda site” in a February 2021 story. Monacelli didn’t think much about the story and went to work on other projects. “Given what I had written,” he says, “and I was citing other sources, which were highly reputable sources, I considered it to be somewhat of a safe thing to write.”

Defamation law in the U.S. was on Monacelli’s side. The First Amendment, according to the First Amendment Center, creates a high bar for those who want to succeed in defamation claims. The First Amendment, however, doesn’t stop people from filing lawsuits. Monacelli’s legal journey started with a letter in August 2021, demanding, under threat of Texas defamation law, the Dallas Weekly “retract and/or correct” the reporting about the Express and “affirmatively state the truth.”

The Dallas Weekly adjusted the story slightly because D Magazine, one of the story’s sources, had revised its report, but the Weekly’s overall characterization of Bennett and the Express remained generally the same.

“They decided to sue me and the Dallas Weekly because the Dallas Weekly doesn’t back down,” Monacelli says. “Everything we’ve written is true or protected opinion.” Suddenly, Monacelli, a freelancer who does not have resources to pay for legal representation, needed help fending off a lawsuit that, according to U.S. legal precedent, had essentially no chance of success. “It was laughable, but it was also concerning,” he says. “I didn’t start sweating in the moment because I thought back to what I’d done and the article that I wrote and the steps that I took to do the journalism properly.”

He received notice, via certified mail, of the lawsuit in October 2021 and posted a request on Twitter, “Anyone got a good good recommendation for pro-bono legal assistance for journalists?”

Reach out to institutions that work to protect journalists. Don’t roll over if you are confident that what you’ve reported is the truth

Monacelli connected with the First Amendment Clinic, which is based in the law school at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, which agreed to represent him and the Dallas Weekly. (Disclosure: I teach journalism at SMU but had no involvement in the case.) “If I hadn’t been able to get pro bono support from SMU,” Monacelli says, “I would have had to start raising money, or I would have had to go take out a loan or go beg some people.”

That’s the point of SLAPP lawsuits. As a freelancer, Monacelli’s time is money, and the lawsuits, however dubious, took time away from his work. Bennett “wins because he made me have to do that,” he said. “If I don’t work, I don’t get paid.”

Monacelli and his new legal team used the Texas Citizens Participation Act, an anti-SLAPP law, which provides a mechanism for meritless defamation lawsuits to be dismissed before they can cause substantial financial, emotional, and reputational harm. Thirty-two states have such laws, but no similar federal law exists. When a person or organization claims it is subject to a SLAPP, courts typically examine the facts of the case and determine whether it should be dismissed or includes enough merit to continue. Anti-SLAPP laws are intended to intervene before journalists or news organizations spend too much time or resources fighting the lawsuit.

A state appeals court agreed in August 2022 that Bennett’s claims constituted a SLAPP, dismissing the case against him and the Dallas Weekly, sending it back to a lower court to decide whether Bennett’s attorney should be sanctioned. Bennett appealed the decision to the Texas Supreme Court in September.

Monacelli emphasizes that journalists must know the resources they have available to them, including sources of free legal representation. “If you’re a journalist, don’t give up,” he says. “Reach out to institutions that say they work to protect journalists. Don’t roll over if you are confident that what you’ve reported is the truth.”

Some of those institutions include SMU, which has one of several First Amendment clinics around the United States that provide free legal representation to journalists. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press has a legal advice hotline, and the Society for Professional Journalists maintains a legal defense fund. London-based Media Defence supports journalists around the world who are facing SLAPPs, to name a few.

Monacelli said knowing journalists’ rights is also important: “Know what the law is and know what your rights and protections are because if it exists, you may be able to lean on it. Just because you’re small, it doesn’t mean that you can’t prevail.”

Get Civil Society Organizations Involved

A money-laundering scheme, criminal networks, secret uranium and plutonium sales, and bribery — the accusations against Paola Ugaz, an investigative reporter based in Lima, Peru, could make a captivating television drama. The plotline, however, is part of a real-life story. She is facing a collection of lawsuits, all of which, according to Ugaz, were concocted to create fear and limit her reporting about Sodalitium Christianae Vitae, a Catholic organization based in Peru.

“Everything is untrue,” she says. “The investigation against me for money laundering, this is the most dangerous one because in this process I can go to jail, they can prevent me from going outside my country, and they don’t have any limit to period of time, so I can be in this case one, two, three, or 10 years being investigated.”

The lawsuits started after Ugaz, a correspondent for ABC, a large newspaper in Spain, and editor of Nativa TV, and journalist Pedro Salinas, who writes for La República and works with La Mula, announced plans to write a second book about Sodalitium Christianae Vitae. The pair published in 2015 “Half Monks, Half Soldiers,” which included 30 testimonials of victims of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse at the hands of the group. Ugaz and Salinas started new projects investigating the group’s finances in 2018.

The pair initially faced defamation lawsuits from José Antonio Eguren, the archbishop of Piura and a member of Sodalitium. Ugaz was sued for posting seven tweets that repeated her reporting about Eguren, his connection with Sodalitium, and the group’s history of abuse as Eguren prepared to meet the Pope in Peru. Salinas was sued for claims he made about him in an article calling him a “Peruvian Juan Barros” earlier that year. Barros, a Chilean bishop, resigned in 2018 after he was accused of covering up sexual abuse by priests in his country. Both lawsuits were filed in Piura, northern Peru, in October 2018. Ugaz says the lawsuits did not have a valid claim and were filed in Piura, rather than Lima, because that’s where Eguren holds the most power.

Salinas was convicted of defamation, given a suspended one-year sentence, and fined about $20,000. Ugaz awaited a ruling when the Catholic Church pressured Eguren to drop the lawsuits. That’s when Ugaz’s story took a turn. Church officials ceased resisting her work, but a network of right-wing, pro-Catholic news organizations and personalities replaced them.

These organizations created and fed off what Ugaz labeled an “ecosystem” of false information about her. Fifty to 60 complaints were filed, some of which became the bases of other lawsuits against her. La Abeja director Luciano Revoredo, whom Ugaz referred to as Peru’s version of Alex Jones, sued Ugaz for defamation in 2020 after she contended La Abeja — a conservative Catholic publication — ran coverage of her that was misogynistic and falsely claimed she was plotting against the Catholic Church. The lawsuit was dismissed in January.

La Abeja has published more than 60 stories about Ugaz since 2018, placing her picture alongside a snake, a prison, and criminal mug shots. When Eguren’s lawsuits were dropped, the site questioned the church’s motives.

Ugaz said finding a network of support has been crucial. She has received letters from the Pope and met with him at the Vatican in November. Ugaz says she hoped meeting with him would have a powerful effect on the cases that are pending against her.

She and Salinas used connections with human-rights advocate Francisco Soberón Zuliana Lainez, who leads the National Association of Journalists of Peru and is on the executive committee for the International Federation of Journalists; Jo-Marie Burt, who works with the Washington Office on Latin America, a human rights advocacy group; and Kate Harrison, who was ambassador to Peru for the United Kingdom, to create a network of support and to get her story out to an international audience.

Ugaz says the network, and the exposure it helped bring to her story, led to help from the Clooney Foundation for Justice, Forbidden Stories, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Media Defence. The groups have provided funding to support her legal costs and helped create international pressure on Peruvian officials to dismiss the lawsuits.

Ugaz says the attacks have been different because she is a woman: “They talk about my body, my intelligence, my family. They put me in a lot of cartoons. They try to be demeaning. [Peru is] a very misogynistic country.”

Ugaz is uncertain when her cases will be decided. The damage, in many ways, is already done. “That’s the problem,” she says. “They don’t have any limit. You get put in a limbo. It’s like continually harming you. They are really happy with this.”

Seek International Attention

Cirman’s collection of orange slips of paper continues to grow — but they can bring good news, too.

Six of the cases against him have been thrown out. While Slovenian defamation law is generally unfriendly to journalists and categorizes defamation as a criminal offense, something emphasized in Reporters Without Borders’ 2022 Press Freedom Index, Cirman says he’s confident all the lawsuits will be dismissed — eventually.

Of course, Snežić doesn’t have to win the cases to accomplish his goals: “He succeeded because no other Slovenian media, which at first were following the story because it was a huge story, now basically no one wants to touch it with a stick because they’re afraid of the lawsuits.”

The lawsuits have also undermined Cirman’s reputation as a journalist, something he’s built during 22-year career, making it more difficult to do other stories. “Other colleagues also see you as a problem,” he says. “When it takes one, two, three years, they start to say, ‘I’m sure he got something wrong.’ You become a one-story journalist. … You want to move on and explore other things, but you can’t because it keeps coming back to you.”

The lawsuits have been less successful in destroying Necenzurirano, which translates to “Uncensored” in English. Still, the lawsuits have caused financial stress.

Cirman incurred about $8,000 in legal fees, a substantial amount of money in Slovenia, since the lawsuits started. He cautions, if the cases go to court, it will be crucial that they are combined into one defamation lawsuit, rather than dozens of individual cases. “Otherwise, we will go bankrupt,” he says.

He’s been helped by two grants, totaling about $8,000, from the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom as well as legal support from SVET24, another Slovenian news outlet, which ran some of the reports associated with the defamation cases. Cirman says support from more than a dozen international journalism organizations has been a crucial weapon against the attacks: “That saved us. Attention is all there is in these cases. We are glad that we are putting the SLAPP issue on the map. We were in contact with the European Commission on Human Rights. We attracted attention and we basically were one of the cases that helped spread the belief that urgent action is necessary.”

The European Union announced recommendations regarding SLAPPs in April, including a mechanism for judges to quickly dismiss baseless lawsuits like those Cirman and his colleagues face as well as cost-covering tools. At the same time, E.U. lawmakers are considering legislation to protect against SLAPPs throughout the bloc.

The potential measure would encourage judges to dismiss unfounded lawsuits against journalists and outlines other tools, such as compensation for journalists from those who file SLAPPs and penalties for the use of abusive lawsuits. The E.U. also recommended member states to increase training for prosecutors and judges to help fight SLAPPs. The E.U. also wants member nations to conduct awareness campaigns to help journalists recognize when they are facing SLAPPs and understand what resources are available to help.

Cirman thinks an E.U.-wide protection is the only solution. Without it, those seeking to punish journalists and limit the flow of information will file in countries without anti-SLAPP laws. That could be a long process.

In the meantime, Cirman and other journalists facing SLAPPs can take heart in Paola Ugaz’s approach: “Fear never has to be your editor. The only answer is more journalism. The best lesson for me and for the others is to continue publishing.”