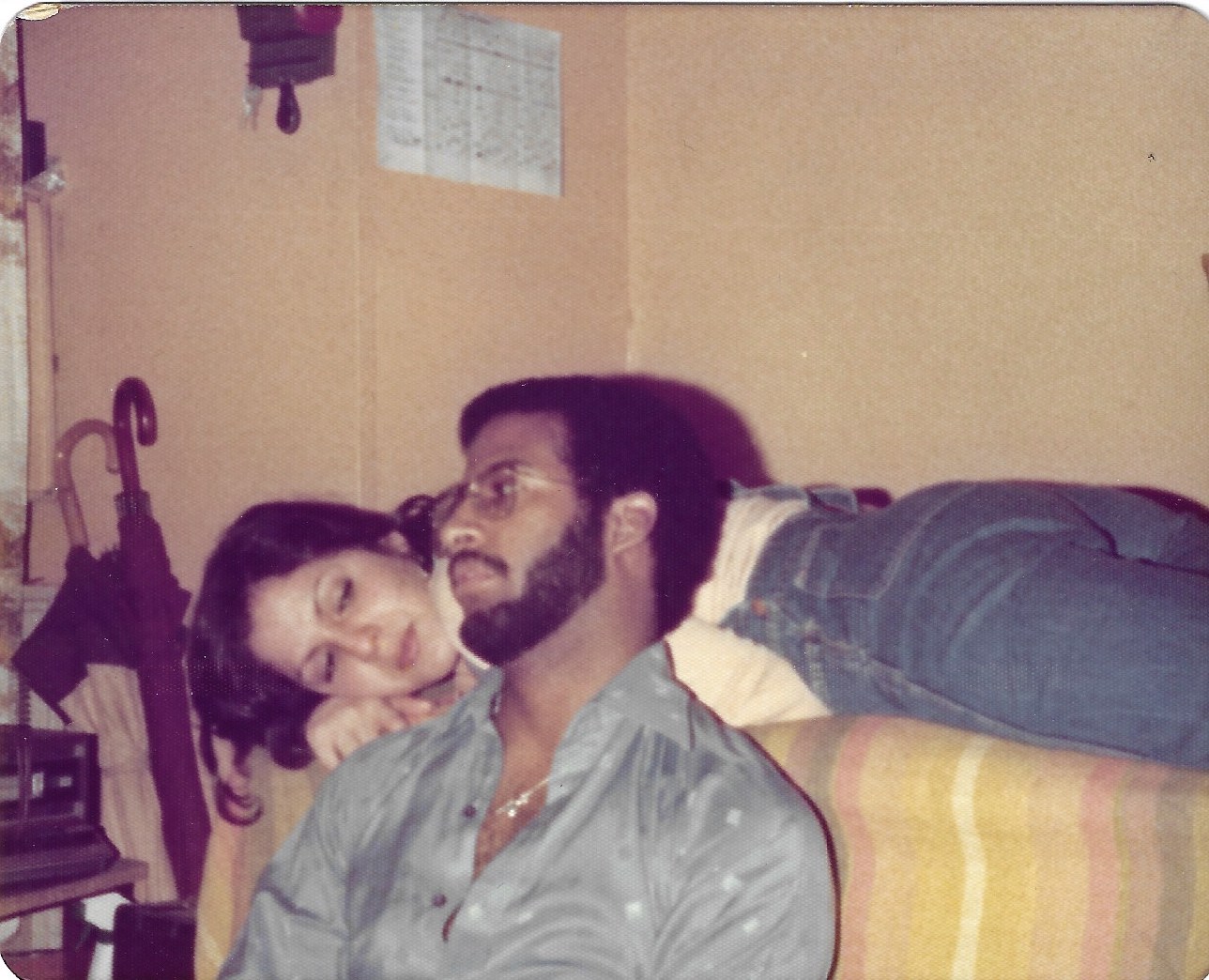

My parents grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in East Harlem, New York City, when it was especially precarious for people living in that neighborhood. A national recession and a local fiscal crisis pushed the city to the brink of collapse. At that time, their predominantly Puerto Rican community was largely ignored by the city government.

Some of the starkest visuals of how neglected East Harlem was then are images of uncollected trash piling up in the streets. For years, the city’s sanitation department infrequently collected trash, and it often rotted on the sidewalks. The issue came to a head in the summer of 1969 when a Puerto Rican activist group called the Young Lords organized the community and took action into their own hands. They collected the garbage and burned it on the streets. It finally prompted a response from city officials.

For me, this story stands out among the many stories my parents have shared about their childhood. They proudly remember this as a moment when their neighborhood refused its predetermined narrative — that their community deserved to silently struggle with poverty.

In the late 1970s, nearly one in five New Yorkers lived below the poverty line. And as the city slid towards bankruptcy, violent crime also spiked, more than doubling between 1965 and 1975. Newspaper and television news reporting from that time often overemphasized this reality in neighborhoods like East Harlem.

This is also when broadcast media shifted to an “eyewitness news” model of reporting, its lens focused on raw images of urban poverty. Instead of having an anchor seated behind a desk, viewers tuned in to watch enterprising reporters who went out to get the real deal from the streets. Neighborhoods like East Harlem featured prominently in these late-night news specials. The community was compared to other impoverished cities in the global south, while heroin addicts, sex workers, and gang members were interviewed with little context for the structural issues that were pushing poverty and crime rates higher in the community. It was a visceral look at crime and poverty for the entertainment of suburban viewers.

But when I hear my family talk about their community, I often hear a story of perseverance. Despite the trappings of poverty, my parents were able to get an education and give back to their community. My mom received a Master’s in Education and went to work as a public school teacher in the neighborhood. My father went to school for criminal justice, and his first job was investigating corruption within the New York City Police Department. They were just two of hundreds of hard-working East Harlem residents who wanted to make their community better. But these experiences and contributions were often overlooked.

The narrow perspectives of my community as one blighted by poverty and crime persisted for decades and supported dangerous stereotypes. When I came of age in the same neighborhood during the mid-1990s, the media’s reporting on drugs and crime was used to justify hardline law enforcement policies. Mayor Rudy Giuliani was in office and ushered in the racist “broken windows” policing practice that targeted neighborhoods like East Harlem and teenagers like me. Anyone from a Black or brown family at that time was almost certainly impacted, directly or indirectly. Having so little control over how my community was represented and feeling the threat of these policing practices every day made me feel powerless. It would take decades more for lawmakers to recognize the damage these policies had done to people who looked like me.

When I decided to become a full-time professional journalist in 2010, I brought the weight of these lived experiences to my work. I made it my mission to bring more nuance to my work because I understood firsthand how painful it could be when your community isn’t fully represented in the news.

As I built my career, I was conscious of how I represented certain communities in writing and in my visuals. A big part of this is personal. I never wanted my work to make anyone feel the way I felt when my community was misrepresented. When I report on those who’ve been traditionally excluded from or inaccurately portrayed by the news, I’ve tried to take extra care in my reporting. Sometimes it’s as simple as asking my sources about the ways they’ve felt harmed by the news media to make sure I don’t repeat the same mistakes in my work.

But I recognize that I haven’t always gotten it right. I’ve underestimated the power of narrative stereotypes and how much they’re embedded into the shorthand of daily, breaking news. I especially see this in my reporting on immigration. While I’m proud of most of my work, some of my pieces have flattened a very complex issue. I often wonder if my coverage at the U.S.-Mexico border helped move the conversation forward or added to the rhetoric.

It’s important to acknowledge that today, more than ever before, there’s a bigger range of voices represented in the news. But inclusion alone is not enough. As more voices are brought into the conversation, journalists also need to be aware of the way we cover certain communities.

This isn’t a novel idea. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, almost every major city in the U.S. experienced rebellions in Black and brown communities. A government review of the uprisings found that underrepresentation and misrepresentation of these communities in the news media added to the frustration that spilled out into the streets. The way we cover communities matters.

I’ve spent much of my time as a Nieman fellow reflecting on how to slow down the news process, specifically when covering vulnerable or underrepresented communities. I believe that it’s important to report with intention, especially when telling stories from this space. For me, this is a crucial piece in addressing power equity issues in news reporting.