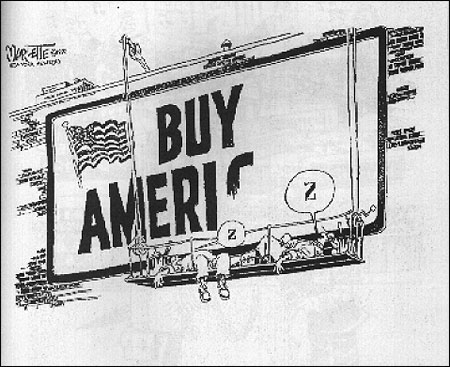

Cartoon © Doug Marlette, courtesy of Marlette.

[This article originally appeared in the Fall 1994 issue of Nieman Reports.]

There was a time when reading the Tuesday page one “Labor” column in The Wall Street Journal was a required exercise for many reporters. There, every week, the bible of business printed short items of interest to those of us who covered labor. There were tidbits from the various government agencies dealing with workers and workplace issues, academic studies on wages and benefits, and a couple of insider items about trade unions.

No more. A scan of recent “Labor” columns revealed items about a professional counseling firm, businessmen who rent convertible cars on their “work” trips, corporate policies toward personal telephone calls (at home and on the road) and the foreign cities least expensive for expatriate American families.

The column is still called a “report on people and their jobs in offices, fields and factories,” but the slug is quaint; except for an occasional item, the column ignores blue collars, farmers and organized labor.

Hardly anyone covers labor anymore. Instead, we have reporters assigned to “workplace issues” who work in the business editor’s domain. Their copy competes for space with market, trade and corporation stories. In Washington, organized labor is an adjunct of the political and congressional beats where the word “union” is sliding with “liberal” into the dustbin of history.

In focusing on “the workplace,” reporters have devoted reams of copy to brokers, engineers and managers who are able to articulate their problems and who closely resemble modern journalists in education and social background. Much less attention has been given to the mechanics, clerks and laborers who are the main victims of recent economic dislocation and to the unions that are their surrogates.

The printed and electronic media have played down one of the great stories of this era, the decline of workers’ real income and the further elevation of upper income Americans. The implications of this widening of social and economic gaps escape many editors even though it means their readers have less money to buy their newspapers or new, high tech electronic services, or the products they advertise.

The U.S. Census Bureau in June reported a sharp increase between 1979 and 1992 in the number of persons earning less than the poverty-level annual wage of $14,228 needed to support a family of four. In 1992, 18 percent of full-time workers earned less than $13,091, a 50 percent increase over 1979 when 12 percent of workers were in that group.

Poorly educated women comprise a large proportion of these working poor, but the share of men in that trap grew 83 percent in those years; the female share was up 16 percent. Nearly half of the group is between 18 and 24.

Another study released last December showed that between 1979 and 1991, average, after-inflation wages paid high school graduates fell 12 percent.

College graduates’ wages remained stable while those paid to individuals with two years’ graduate work rose 8 percent. The disparity in pay between high school graduates and college graduates went from 38 percent to 57 percent in that period.

Labor Secretary Robert Reich, who released the study, observed: “A society that lives with a very large gap between the well-educated and everyone else makes for an unstable society.”

The long-term risk is the creation of a rigid three- or four-level class structure from which America escaped with the development of a mass middle class and firm belief that each generation could live better than its predecessor. Trade unions were major builders of the working middle class and the dream of ever-upward mobility.

Joe Klein of Newsweek recently suggested that we may never see again “a country where a single semi-skilled factory worker can comfortably support a family.” Does that mean a return to a working class of men and women living in company-owned housing, trudging off to minimum wage jobs in order to compete with workers in India or Bangladesh?

What about all the newly created jobs? The Washington Post found that between 1989 and 1993, “new growth” companies added a half million low pay jobs and a million average wage jobs while cutting more than a million high wage jobs. The net gain was 459,000 new jobs at either low or average wages.

In a country where nearly every social and economic group is organized, only the labor movement provides political representation to these lower paid workers regardless of their membership or non-membership in a union. Organized labor is the one lobby that campaigns for raising the federal minimum wage, which is the lifeline for many of these working people.

The contemporary press, with a few exceptions, covers them as an amorphous, anonymous group, not as working men and women who want their children to fulfill the American dream. Alfred Balk, who teaches journalism at Syracuse University, summed up the journalistic treatment of workers’ issues last year in Nieman Reports:

“Day-to-day coverage tends to be a business-as-usual recording of layoffs, corporate downsizing and wage and job-opportunity shifts as if these were recession phenomena little related to something greater. This clouds comprehension of an economic upheaval that is far more than a recession—it is a revolution.”

There was a time when the labor beat held front rank. It attracted first-class reporters, produced great human-interest stories on a broad front of social, economic and political issues and brought readers to newspapers. Blue-collar shift workers were major subscribers to the big afternoon newspapers in Detroit, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Buffalo and Chicago; the morning papers with their stock tables were for the white collars.

This photo of the 1937 painting “Employment Agency” by WPA artist Isaac Soyer is reproduced by permission, Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photograph by Geoffrey Clements, © 2000: Whitney Museum of American Art.

A good labor reporter not only recorded what was happening to men and women on their jobs, but also reported on the developments within unions, communities and politics. Union contracts led to other stories in City Hall, the State House and Congress.…

Labor reporting has declined in parallel to the perception that organized labor is declining as a dynamic, mass social and political movement. Membership in unions has declined dramatically in proportion to an expanding work force, but the actual number of union workers is remarkably stable. In 1992-1993, the AFL-CIO collected per capita payments for 13.3 million members of affiliated unions compared with payments for 12.6 million members in 1954-1955. There may be another million members for whom the affiliates do not pay per capita dues.

In addition, there are hundreds of thousands of other workers in other collective groups that bargain for contracts and improved working conditions but are ignored by the press. When all of the dues-payers are multiplied by the number of family members, retirees and sympathizers, no matter how one plays the numbers game the organized labor movement is still the largest single, multifaceted social force in the United States.

The disdain for organized labor reflects other changes occurring in American society that are reflected in the conduct of the media. Newspapers, which still set the agenda for serious electronic journalists, have become an elite form of media, moving away from a formerly loyal mass audience to cater to the social and financial interests of a smaller, older, richer class of readers.

“Citizens now perceive the press as part of the insider’s word,” David Broder, senior political writer for The Washington Post and one of the few national reporters who keeps in regular touch with labor leaders, has observed. “We have, through the elevation of salaries, prestige, education and so on among reporters, distanced ourselves to a remarkable degree from the people we are writing for and have become much closer to the people (experts and politicians) we are writing about.” Broder cited a 1992 debate over the extension of unemployment benefits to two million workers that was covered by the Post as “a tactical battle between Bob Dole and George Mitchell” and between Congress and the President.

“The one perspective that is missing from these stories is the viewpoint and stakes of the two million people who will or will not get a supplemental unemployment benefit,” Broder continued. “Why? Because most of us don’t know these people. They are not our friends.”

William Greider observed in the book “Who Will Tell the People” that the death of urban afternoon newspapers caused the loss of a “singular angle of vision.” “Newspapers do still take up for the underdog, of course, and investigate public abuses, but very few surviving papers will consciously assume a working-class voice and political perspective.”

The Washington journalism establishment repeated itself in covering congressional passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement. After ignoring the AFL-CIO as politically irrelevant, these media mavens were surprised to find that NAFTA was nearly defeated by organized labor’s opposition.

“The Washington press has an increasingly corporate perspective,” Greider commented. “They identify with status quo ideology. The press could not bring itself to take the labor opposition to NAFTA at face value. In another era, 20 years ago, the press would be out talking to these people. Now it’s all done through focus groups and public opinion data.”

Speaking of the “political elite,” Richard Harwood wrote in the Post: “We socialize with them, talk the same language, have the same interests, live in the same neighborhoods, share life styles, schools for our children, clubs and poker games. It is no wonder that the pictures of the world we present to the newspaper audience and the spin we put on them are, in the strict meaning of the word, the ‘propaganda’ of the ruling class.”

Slaves to consistency, the sheep-like press pays little attention to the grassroots campaigns for President Clinton’s national health plan conducted by unions and the American Association of Retired Persons joined by the American Medical Association. More attention has been paid to the lobbyists for business.

Clearly, the outlook of reporters and editors has changed over time. In my generation, the Greider-Broder- Harwood era, we worked with many great reporters who had no college degrees, but great instincts and feelings for working people. My own attitude was sharpened by three summers’ work in the huge Lackawanna Works of the Bethlehem Steel Corp., where at 18 I became a member of the United Steelworkers of America. My education among 16,000 steelworkers was equal to, and perhaps superior to, what I learned later among 12,000 students at the University of Iowa. But today’s problems are greater than those cited by a bunch of old guys grousing about the “good old days.”

By ignoring any real concerns of working people, newspapers have accelerated a broad trend against reading of any printed news. Workers who leave home in the morning without reading a newspaper come home and watch the evening television news. Instead of making their publications more interesting to workers, publishers and editors are desperately trying to book passage on the new electronic information highway where their fellow travelers will be only upper income.

On the other hand, all media organs cover issues of minority and women’s rights, partly because the newspapers, networks and local stations have responded to pressure to make their staffs more reflective of society as a whole. The younger journalists make sure their bosses are sensitive to issues of individual rights while collective rights are put aside.

The new journalists, with few exceptions, do not see workers’ rights as an issue of civil rights even though organizing and joining unions are rights protected by the Constitution and 60- year-old federal law. The “me” generation will complain of personal mistreatment without taking the logical response: collective action.

Workers in a broad perspective are often patronized and their grievances treated as economic and social phenomena. Younger journalists have exaggerated views of the skeletons in labor’s closet—corruption, rigid work rules, bloated payrolls. They view organized labor as a monolith, not as a collection of idiosyncratic units; they do not recognize unions’ interests as workers’ interests.…

Certainly, the era of mass organizing and frontal confrontation between labor and government or big business has passed along with the charismatic labor personalities such as Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers and John L. Lewis of the Mineworkers. Still, there are good “workplace” stories awaiting broader discovery.

It is a mistake to concentrate workplace coverage on unions, but it is a bigger mistake to ignore them. Modern reporters with their lack of historic memory have failed to see the internal dynamics within unions to see how they have given strength to the civil rights movement and enrolled minorities in numbers at least double their proportion in the overall population. Once slow to join unions, women now represent a substantial portion of all members and have moved into key staff positions, although they are underrepresented at the elected officer level.

While the hierarchy of the labor movement seems tired and aged, there is a new generation of younger, innovative leaders working directly on workers’ problems at regional and local levels. This is where some of the best “workplace” stories can be found.

Unions have always limited their contacts with the press. They are not equipped to finance the kind of public relations and marketing campaigns their enemies mount. Instead of looking for p.r. types to guide them, reporters should read union newspapers that report labor activities at every level.

The organized labor movement stands out for its broad agenda in an age of single-issue, narrow interest politics. Despite its troubles, the labor movement enjoys a consistent, positive reputation as measured over nearly six decades by the Gallup Organization.

As Robert Kuttner, one of the few national columnists who can be called a liberal, concluded recently: “Labor remains the most potent counterweight to the increasing intellectual, ideological and political dominance of organized business and concentrated private wealth.”

Murray Seeger, a 1962 Nieman Fellow, wrote for the News in Buffalo, the Plain Dealer in Cleveland, the Times in New York and Newsweek from Washington. For The Times in Los Angeles he wrote from Washington, Moscow, Bonn and Brussels, with a specialty in economics. Bored in the West, he went to Singapore to write and edit for the Straits Times. He opened doors and windows as Information Director of the AFL-CIO and Assistant Director for External Affairs of the International Monetary Fund.