Walter Cronkite and a CBS camera crew use a Jeep for a dolly during an interview with the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, during the Battle of Hue City, Vietnam, 1968. Photo courtesy of the Still Picture Branch, National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

[This article originally appeared in the Summer 1991 issue of Nieman Reports.]

“The media, be it press, TV, radio or other form, impresses me and, I’m sure, the general public, as being a voracious, insatiable animal. It claws, snaps, tears at and insults just about anyone it faces, especially those feeding it information. I sometimes wonder whose side the media is on.” —An angry reader, in Letters, St. Petersburg Times, February 6, 1991

“The American media surrendered to a barrage of propaganda…a credulous and jingoistic press.… The administration…knew that it could rely on the media’s complicity in almost any deception dressed up in patriotic costume…a servile press…” —Lewis H. Lapham, Editor, Harper’s, May, 1991

In the Persian Gulf crisis the diplomatic, political and economic reporting was manipulated by the Bush Administration as much as the military press, only more subtly.

The Administration engaged in intensive news management to shape and exploit crisis information far beyond the battle zone throughout the six-month buildup for the war, as well as during the six-week conflict. Indeed, the press was maneuvered into looking like a “voracious, insatiable” inquisitor to some Americans, and to others just the opposite, a “credulous…jingoistic…servile press.”

Surpassing any injury to journalistic pride, however, is the capacity that the Bush Administration has demonstrated for shrinking First Amendment rights in “a new world order.” A press so readily manipulated during months of preparation for war tempts fate in either peace or war.

Major news organizations that have protested “virtual total control” of the press by the Pentagon during the Gulf War have narrowly focused on direct constraints in the war zone—military censorship, restricted press “pools,” military “monitors.” From the first week of the crisis, however, the White House, Defense Department, State Department and other agencies used a dozen more discreet techniques to manipulate the substance, flow and timing of nonmilitary as well as military information to protect and support the Administration’s policy. These techniques included the calculated use of deliberate ambiguities, evasions, half-truths or outrightly misleading information.

The news management of Operation Desert Shield might well have been dubbed Operation Washington Shield. As journalists should know better than others, the less blatant the control of news, the more effective it is.

Walter Lippmann, drawing on his own World War I experience, observed in his classic study, “Public Opinion”:

“Military censorship is the simplest form of barrier [to public information] but by no means the most important, because it is known to exist, and is therefore in certain measure agreed to and discounted.”

The Bush Administration achieved a level of control over the American print and broadcast press and public opinion that Presidents Johnson and Nixon would have given anything to have had during their turbulent years of the Vietnam War. It was months into the Persian Gulf crisis before allusions to a new “credibility gap” were made by frustrated reporters, but that stigma did not adhere to the Bush Administration. It set out from the beginning of the crisis determined to manage the news in a manner that would make it no easy mark to attack for deception.

After the February cease-fire in Iraq, however, the contrast between a controlled or managed press and an uncontrolled press was inescapable. A free press revealed the desperation of Iraq’s Kurds, forcing the Bush Administration to change policy and aid Saddam Hussein’s latest targets, who had been encouraged to revolt by the President’s own loose rhetoric.

Until then, the Bush Administration’s hold on the American press stretched from the Persian Gulf to the United States and back—literally. Its news managers not only could make all bombs targeted on Iraq look smart; they could equally make frustrated reporters at televised briefings look stupid, or appear to be snarling watchdogs.

When officials discovered the hostile reaction by average Americans to the questioning of spokesmen in uniform, they rehearsed the press briefings to sharpen the antagonistic perception. Ergo, a press that “claws, snaps, tears at and insults just about anyone it faces, especially those feeding it information.” The reality was just the opposite press failing: inadequate questioning, skepticism, probing.

It was not the Administration’s objective simply to taunt the press. The purpose was to diminish and discredit it as a competing force in shaping public opinion, even though the Bush policy had overwhelming support from the public and from the press itself.

The crossfire over press performance has boxed the compass. It has stretched from Pentagon encomiums for “best war coverage”—which makes experienced reporters wince—to charges that reporters “more often resembled government stenographers than newsgatherers.”

New York Times columnist Tom Wicker, a persistent and thoughtful critic of the news coverage, saw a “dangerous” precedent in the Bush Administration’s easy success in limiting what it wanted the public to know. “Perhaps worse,” Wicker wrote, “press and public largely acquiesced in this disclosure of only selected information.”

His columnist colleague at the Times, Anthony Lewis, called for urgent “self-examination… in our business….” He found “most of the press…not a detached observer of the war, much less a critical one,” but “a claque applauding the American generals and politicians in charge.” Lewis labeled “television…the most egregious official lap dog during the war.”

But First-Class Reporting, Too

Blanket characterizations pro or con, however, are ill-fitting for anything as diverse and discordant as the American print and broadcast press. In the record number of columns of space and hours of broadcast time filled by any American crisis in a comparable time span, there were innumerable examples of balanced, penetrating, first-class reporting, as well as countless pieces of shallow, witless, gullible work.

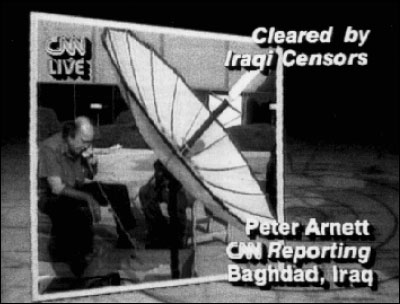

No segment of the press was uniformly in one category or another: clearly not television. Cable News Network was indispensable for news coverage, with Peter Arnett in Baghdad as an extra bonus—and anti-press target. Public television’s MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour consistently provided more balanced and penetrating news, debate and analysis than any, and sometimes all, commercial channels.

This article disproportionately cites news coverage of The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, all with large staffs and all available for home delivery in Washington. They therefore have special impact on Congress and on the large Washington-based national and international press corps often influenced by their coverage.

Congress and press have an important symbiotic relationship of stimulating each other into public scrutiny of government that is not well-known outside the Washington-New York-Boston corridor. In the Gulf crisis the Times, Post and Wall Street Journal all supported Administration policy, along with most of the nation’s press, contributing to the fact that in this crisis cross-stimulation of press and Congress [failed] to produce a more probing examination of Administration policy. For the major news organizations were misled no less than the smaller ones.

Out of political fear of challenging the broadly supported commitment of American military forces to a war zone that could erupt before the congressional elections in November, Congress virtually abdicated its responsibilities in scrutinizing Administration policy.

Except for limited hearings, Congress avoided questioning crisis policy until jolted into debate by the Bush Administration’s carefully timed, post-election disclosures that it was doubling American forces in the Gulf, and openly shifting from economic sanctions and military pressure against Iraq, to offensive war. With American and coalition forces poised for a U.N. authorized war, Congress, forced to choose, voted for it after its first real debate in the crisis. Such a debate months earlier would have stimulated deeper press questioning of U.S. policy and vice versa. There Administration strategists-news managers could claim a double success.

Journalism’s highest awards this year went to news coverage of the Gulf crisis, along with profound individual journalists’ criticisms of press performance in a war that the rest of the nation cannot celebrate ecstatically or exhaustively enough.

Vietnam a Reason for Controls

Just what caused the American press to incur so much damage to its own self-esteem in this war, in contrast to its pride in vigorous reporting in the Vietnam War, will be explored and debated for years to come. The unending criticism of the American press for the loss of the Vietnam War, however ahistoric, contributed heavily to the controls imposed by the Bush Administration in the Gulf War. A journalistic cynic might add, at least the messenger cannot be shot for losing this one.

But the resourcefulness of the Bush Administration, and the magnitude of the journalistic task, should not be underestimated. Veteran reporters did penetrate many of the Administration’s calculated ambiguities, half-truths, evasions, misleading guidances and other tricks of the news management trade.

There was unquestionably insufficient awareness in the press as a whole, however, of the added demands that war or the threat of war make on press vigilance: The inherent adversarial relationship between government and press is at its peak in wartime, when the President is both Chief Executive and Commander in Chief of an authoritarian structure. Truth is the first casualty not just in war, but equally in preparation for war, for both rely heavily on secrecy, evasion and deception.

What is disclosed and concealed from press and public in the initial stages of a crisis has extra criticality for all that follows. The press invariably is at its most vulnerable point when the rationale for crisis action is put forth.

“It is not truth” the government is intent on communicating at that time, “they’re selling something they’ve done,” Hodding Carter III, State Department Spokesman in the Carter Administration, and now a television commentator and producer, explained on the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour on September 30, 1990.

“Panama invasion, Grenada invasion” and in other deployments of military force, Carter continued, “the press initially accepts. It then begins to question.”

However, “for the first week after any military engagement,” Carter emphasized, “there is virtually never going to be sustained questioning of anything the government does— particularly the assumptions. It sometimes takes a month, it sometimes takes a year….”

Indeed, dozens of fundamental questions were not raised in the rush to report the American military plunge into the Persian Gulf. President Bush, for example, was not asked whether the Bush Administration took time to explore not only diplomatic alternatives, but also far more limited forms of U.S. military intervention, in differing configurations. If the press had done so effectively it could have learned very early in the crisis that the Administration had plunged into a hasty policy choice without exploring the implications with Mideast experts in or outside the government.

In the Gulf crisis, domination of public opinion was particularly essential for the Administration to sustain a venturesome and improvised policy, which was launched cloaked in calculated ambiguities to conceal its dimensions and intentions.

Even though the American troop deployment was ennobled as the core of a multinational force, fulfilling the United Nations’ dream of collective security, the public had to be conditioned to tolerate a huge military commitment to war without warning.

No censorship of war zone controls could have long concealed the mushrooming of an American force from 50,000 troops—the target originally given to the press—to 540,000 in six months, matching peak U.S. troop strength in Vietnam after a decade of buildup. Exceptional news management was required to rationalize the growth of a defensive Desert Shield operation and to screen its seamless transformation into an offensive Desert Storm.

Controls Needed to Sustain Strategy

Sophisticated information control techniques were needed to sustain simultaneously the interwoven diplomatic, political and economic components of U.S. strategy. They supplied the critical domestic and international support for American military power in the Gulf.

A disclosure at the start that at least 200,000 to 250,000 American troops were planned in the force level discussed in President Bush’s first meeting with his military at a Camp David meeting on August 4, just two days after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, could have played havoc with any news management. That would have aroused immediate questions about American offensive military intentions, United States seriousness for a diplomatic solution of the crisis, and prospects for any United Nations-endorsed multinational force, or cost sharing of the venture.

No American President has thrust the United States into a major war so swiftly and massively. The day after the invasion of Kuwait, August 3, the President made a personal pledge to Saudi Arabia’s Ambassador to Washington to give that nation powerful American military support. By August 5, as he returned from Camp David, the secret planning to topple Saddam Hussein had begun, and the President stunned even the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff by publicly pledging to reverse the invasion of Kuwait. On August 6, American jet fighters and the 82nd Airborne Division began flying into Saudi Arabia. The news dominated American headlines the next day.

President Bush was determined to conceal both the magnitude of the American deployment and its full purpose, but he and his advisers also wanted to avoid a charge of crass deception. The President, therefore, in his first press conference August 8 on the troop deployment, deliberately left open the option for an offensive military strategy, but spoke only of defense, and referred all questions about the size of the American force, or other military factors, to the Pentagon. That figure, given to the press on “background”— where it would not be open to on-the-record challenge—was the misleading figure of 50,000.

That initial press conference on troops to the Gulf offers a primer in American news management.

President Bush said U.S. troops were entering Saudi Arabia “in a defensive mode right now,” and it was “not the mission to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait.” He went on to say “We’re not in a war. We have sent forces to defend Saudi Arabia” and “other nations will be participating….”

Veteran reporters like R.W. (Johnny) Apple of The New York Times, with extensive diplomatic and political experience, quickly detected many of the calculated ambiguities in the President’s remarks. To call the U.S. military mission “defensive,” Apple wrote the same day, August 8, “really applies only in a tactical sense.” The objective of American air, sea and land forces, including “a de facto naval blockade of Iraqi commerce”—labeled sanctions— he noted, was “intended to help force President Hussein to pull back” from Kuwait.

Furthermore, Apple reported, “although the White House and the State Department continued to express anxiety about the possibility of an invasion” of Saudi Arabia (to justify sending large ground forces), “there were no signs of [an invasion] on the ground, and some analysts continue to believe one unlikely.” Apple had deftly raised several caution flags for readers.

But Apple’s story, and the print and broadcast press across the United States, fell victim to “background” news management on a key factor that went into the headlines, the grossly misleading figure of 50,000 troops as the projected size of the U.S. force. His lead read: “Thousands of elite United States troops, the vanguard of a force that senior defense officials said may reach 50,000, took up positions in Saudi Arabia today as President Bush vowed to defend the Middle Eastern kingdom and its oil reserves, the richest in the world.”

And news analysis written the same day for The Washington Post by Patrick E. Tyler, who had served as a foreign correspondent in the Iraq-Iran war (during the Gulf crisis Tyler switched to The New York Times), wrote that the United States had “contingency plans to deploy up to 50,000 or more ground troops” to Saudi Arabia by the end of the month.

Decision Reached at Camp David

The Washington Post on August 9 published the first behind-the-scenes account reporting that the President’s decision was reached hastily on August 4 at Camp David. There, White House reporter Ann Devroy and political reporter Dan Balz recounted, Defense Secretary Richard B. Cheney, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin L. Powell, and Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, laid out the military options for the President.

That account contained new pro- Administration information about the sequence of events, with the President as the central, “speed-dialing” figure in launching the troop deployment, convincing Saudi Arabia it needed U.S. troops, and negotiating with other world leaders.

Missing from that report, however, and also from a more revealing account in the Post on August 26 about the Camp David meeting, written by Washington Post editor-reporter Bob Woodward and reporter Rick Atkinson, was the most salient fact: that an initial force of 200,000 to 250,000 troops was in the plan presented by General Schwarzkopf to President Bush.

It was not until after the war, on May 2, that those important numbers appeared in the Post, coupled with disclosures that punctured the news-managed image of constant unity and harmony among the crisis managers, in excerpts from Woodward’s book, “The Commanders.” The news managers had successfully masked the original large size of the American force concept when that was publicly volatile. Also suppressed was any timely news of General Powell’s strong reservations about shifting from sanctions and military pressure against Iraq to an offensive strategy—the argument the Democrats lost when Congress voted in January to support President Bush.

Number Imbedded in Other News

The crisis therefore began with public misinformation about its expected magnitude, and the misleading number of 50,000 became imbedded in diplomatic, political, economic and other early crisis news, analyses and interactions around the world.

Editors and reporters soon discovered they had been gulled as force levels quickly swept past the 50,000 mark. They generally took that in stride as a cost of “background” gamesmanship; but a pattern for news management had been successfully launched.

Early on, therefore, it was widely recognized in the press, in Congress and elsewhere that the Administration’s stated policy contained numerous evasions, contradictions and unanswered questions. They were almost as likely to be winked at or rationalized in the press, however, as focused on.

After the first full surge of American troops reached the Gulf in August, Time magazine columnist Hugh Sidey wrote: “…Bush keeps moving: White House to Camp David to Pentagon to Kennebunkport to wherever. He pops up to shake a fist, then pumps out a smoke screen of fuzzy gray words. The blockade is an ‘interdiction,’ the detained Americans are not called hostages, and what is happening is not war but a defensive operation. Bush’s press conference last Tuesday sounded like a court deposition—his lawyers and his rights under the U.N. Charter.

“While the world was watching Bush…[the U.S. military] sent more men and material further and faster than at any time in history. This huge cavalcade was not exactly secret, but nearly a week went by before the vast size of the operation dawned on an astounded world.…”

For the news magazines, the President’s apocalyptic comparisons of Saddam Hussein and Adolf Hitler were rich nourishment for magazine covers, Armageddon-like language and battle-plan graphics which newspapers hurried to match.

U.S. News & World Report in late August produced a special double issue on World War II and the Gulf crisis, headlined “Defying Hitler”—with Hitler, Churchill and Roosevelt on the cover. “By next month,” Newsweek informed its readers at the end of August, “the Americans will be as ready as they’re going to be” in the Gulf, “with about 125,000 combat troops and support personnel in the theatre.”

Beyond manipulating the media about military aspects of the crisis, the Administration had numerous nonmilitary priorities, requiring varying levels of concealment, obfuscation and partial disclosure. They ranged from finding a path through the Arab world’s suspicions of the West, and the constant Arab-Israeli crisis, to inducing Western allies and Third World nations to join the multinational force and offset the huge costs of the crisis.

At the same time, the Administration had to sustain the precarious and unprecedented consensus against Iraq that it achieved among the Big Five holding veto power in the U.N. Security Council. That required constant diplomacy to retain qualified support from the Soviet Union, for years Iraq’s prime arms supplier, and the uneasy toleration of China—all for a price.

Indeed these requirements all came with diplomatic, military and economic prices, which today are still unfolding.

This flood of developments engulfed a somnolent press, Congress and nation in the vacation-oriented month of August. Even if there had been no news manipulation to compound the task of short-staffed news organizations, they could barely cope with the surge of information pouring out of world capitals about the Gulf crisis: military, refugee, hostage, oil, diplomatic, religious, political, economic and other news, to be explained in the American context.

And to do that, the press itself had to crash-learn the fundamentals of the Gulf region. That meant everything from geography, turbulent history, disparate cultures and punishing climate, to the boggling complexities of nationalism, shifting loyalties and leadership, and alignments.…

But the most effective news controller was the President himself, the dominant generator of information. With his whirlwind style of telephoning, he was global diplomatic-military strategist, Commander in Chief, information central for his own advisors, chief spokesman, and chief censor.

The President’s disarming affability and frequent availability to the press obscured the reality that he and his advisors were manipulating public opinion with the intensity of a ruthless American political campaign, transferred to the international scene with a diplomatic gloss.

As a consequence, protests by American news organizations against Defense Department control of the press during the Gulf War do not reach the underlying problem that confronts the press. For news management was government- wide, without rules and regulations comparable to restrictions to the press in war zones. And the administration is free at any time, without waiting for a crisis or a war, to resort to that abnormal level of news management.

This is not to denigrate in any way the protests raised against explicit press controls, but rather to expand the focus of concern.

Organizations that protested [against explicit press controls] to Defense Secretary Cheney on May 1 were: four television networks—CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN; Time and Newsweek, the Associated Press, plus The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, and the Cox Newspapers, Hearst Newspapers, and Knight Ridder Newspapers.

Newsday columnist Sydney H. Schanberg labels those groups the press that “behaved like part of the establishment,” and now is “feeling embarrassed and humiliated and mortified.”

Schanberg, who won a 1976 Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the fall of Cambodia, was one of five independent writers who joined 11 smaller news organizations in an unsuccessful legal attempt to block the Pentagon’s press controls on constitutional grounds, before full-scale warfare in the Gulf began in mid-January. Those publications included The Nation, Mother Jones, The Progressive, The Village Voice, and Texas Observer.

Schanberg argues that the problem the press has is “its own scars from Vietnam. And Watergate. We were accused, mostly by ideologues, of being less than patriotic, of bringing down a Presidency, of therefore not being on the American team. And as a professional community we grew timid, worried about offending the political establishment. And that establishment, sensing we had gone under the blankets, moved in to tame us in a big and permanent way.”

Only the Press Can Heal Itself

Many journalists nod in agreement; many disagree. That is the nature of the American press. But there is a sizeable group in between.

For example, a leading participant in the protest filed at the Pentagon was Michael Getler, Washington Post Assistant Managing Editor for foreign news. He wrote in the Post’s Outlook section on March 17 that “the civilian and uniformed leaders of the U.S. military did a pretty good job of mopping up the press in Operation Desert Storm. No one seems to care very much about this except several hundred reporters and editors who know they’ve been had.”

But Getler and two others at the Post also are proud of two Pulitzer Prizes for Gulf crisis work (one to Caryle Murphy, for 26 precarious days as the only American newspaper reporter in Kuwait chronicling the Iraqi invasion; a second to columnist Jim Hoagland for Persian Gulf and Soviet affairs commentary) plus a string of other awards.

What the Gulf crisis has done to the press, and also for the press, is to make its more reflective members look with wider eyes at the current role of journalism in the American structure. It needs many things; if its relevance shrinks crisis by crisis, it obviously will reach irrelevance. To prevent that, the press would be foolish to wait for government to resolve its problems; government is an adversary and knows it. But it would be invaluable to try to determine, perhaps by survey, what proportion of publishers and editors who pay lip service to that credo actually believe it—and act on that premise.

One of the stinging aspects of the Gulf crisis was ridicule of the press, along with the more familiar reactions of anger or indignation. All underscore the inadequacy of press efforts to explain its functions to the public. Why not be more candid with the public? Why not tell the public what the press does not know? Or caution the audience that a story is of questionable accuracy? Or in time of war frequently inform the reader-viewer-listener that all participants are engaging in propaganda, and the only sound guideline is caveat emptor?

Above all, the press must recognize that its vigilance has slackened markedly since the beginning of the Reagan Administration. Its wounds in the Gulf crisis, therefore, were primarily the product of its own vulnerability. No one can heal that damage except the press itself.

Murrey Marder, Nieman Fellow 1950, went from copy boy (1936) to reporter at The Philadelphia Evening Ledger, to Marine Corps Combat Correspondent in World War II. In 39 years at The Washington Post his reporting helped topple Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy in the 1950’s. In 1957 in London he launched the auspiciously named Washington Post Foreign Service—originally just him. He was one of the creators (1965) of the term “credibility gap” to describe the Johnson Administration’s information dilemma in the Vietnam War; a writer of the Pentagon Papers disclosures (1971), and ultimately Chief Diplomatic Reporter of the Post. He retired in 1985 for further research and writing on manipulation of perceptions in foreign affairs.