Every weekend, Tom Grundy plays a game of cat and mouse. The Hong Kong Free Press (HKFP) editor-in-chief opens his computer to 12 livestreams of the Hong Kong protests while trying to untangle dozens of threads on the encrypted messenger app Telegram. Meanwhile, two to three reporters are deployed to the streets; gas masks, helmets, phones, and laptops in tow—so they can file, tweet, and livestream all at the same time—chasing protest flash mobs across the Chinese territory. Such is the fluid, unpredictable nature of the protests—as the Bruce Lee-inspired clarion call goes: “Be water.”

“Unlike most of the protesters,” says Grundy, “we’re looking to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

That’s what happened the night of August 11. As is the usual drill for the protests, now in their 18th week, peaceful marches devolved into scattered clashes among thick plumes of tear gas. Protesters lobbed Molotov cocktails and police fired tear gas and rubber bullets inside a metro station. But that night, street clearances took a new turn when several police officers disguised as protesters—dressed in all black, yellow hard hats, and respirators—arrested a protester. They wrestled him to the ground and pressed his face into a pool of blood. Through the legs of riot police trying to block his view, HKFP reporter Holmes Chan caught the action, the first clear proof of police acting as undercover operatives.

“We are there to keep both sides accountable,” says Grundy, a British native living in Hong Kong since 2005. “That’s why we’re on the frontlines.”

It was a long summer for HKFP, the only nonprofit, independent English-language news source in the city. Grundy co-founded the site in 2015 out of fear for the city’s press freedom. Since protests erupted in June, the bilingual team of four has been working round the clock to cover Hong Kong’s worst political crisis in decades. What began as largely peaceful demonstrations over a hated, now-shelved extradition bill has morphed into a democratic movement against Chinese interference in the semi-autonomous region. As the city’s leader, Carrie Lam, hamstrung by Beijing, refuses to concede to any further demands—including free elections and an independent investigation into police brutality—the government only leans more heavily on the police. Demonstrations now regularly end in vandalism, police violence, and mass arrests.

The Hong Kong protests have been a major boon for independent media outlets

The unrest has drawn the fierce ire of China. On October 1, the 70th anniversary of Communist rule in China, President Xi Jinping reminded the world in a massive, missile-clad parade of the country’s bottom line: national sovereignty. Hong Kong’s mass protests mark a sharp repudiation of that and the most critical threat to its leadership in decades. While authorities remain tight-lipped on the matter, China has increasingly expressed fury over five months of unrest—an endurance that even surprises protesters—as it tries to contain dissent over fears it could spread like a contagion to the mainland and embolden Taiwan, a breakaway nation in the eyes of China, in the run-up to its presidential elections in January. The fear is also that Hong Kong becomes a pawn in the ongoing U.S.-China trade war. China has conducted phone checks of travelers to and from the mainland as well as detained lawyers, journalists, and diplomats. State media regularly vilifies the “riots” in Hong Kong and has heavily broadcast military exercises on the border—though as more an act of saber-rattling. Most recently, its fury is also being felt internationally, as Beijing lashes out at companies that show any semblance of support of the protests, including the NBA, Activision Blizzard, and Apple.

Police force has dramatically escalated in recent weeks. At the October 1 demonstrations, police fired six live rounds, one of which shot an 18-year-old student in the chest. That same weekend, police shot an Indonesian journalist with a projectile, blinding her right eye.

The protests have been a major boon for independent media outlets, namely: Hong Kong Free Press, Stand News, Initium Media, and CitizenNews. As fundraisers and subscriptions show, a free press remains a core public value, especially as the protests have introduced a new level of physical threat. But the fundraisers belie deeper, long-term struggles with financial security and Chinese encroachment. As Hong Kong’s strong tradition of print recedes and pressures mount, the onus has fallen on digital media outlets to keep up with an ever-changing, polarizing movement and to tell the Hong Kong story. As these outlets face increasing restrictions, the independent press is standing firm and banking on public support for survival.

“I don’t think we have taken advantage of all the space in the cage,” says Ying Chan, veteran journalist and founding director of the Journalism and Media Studies Centre (JMSC) at the University of Hong Kong. “Journalism is an art of possibilities.”

Hong Kong’s press freedom rests on the same fragile framework as the Chinese territory: One Country, Two Systems. It was devised when the British returned Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997 to maintain the city’s endowed civil liberties, including rule of law and free speech, in sharp contrast to China’s tightly controlled press. Many major international news outlets base their Asia offices here, and the city remains the only place on Chinese soil where the Tiananmen Square Massacre can be openly commemorated.

The gravest threat to that freedom—and the issue at the heart of the protests—is the dismantling of that framework due to the rise of a more authoritarian China. The steady erosion of media began in 2003 after a controversial proposed National Security Law drew half a million people to the streets—previously the largest public demonstration until this summer—over fears it would threaten freedom of speech. What followed was a tightening of Hong Kong media, mostly through heavy corporatization. This is known as the so-called “mainlandization” of the media, which seeks to integrate Hong Kong into the mainland before the 50-year deal of One Country, Two Systems expires in 2047. Compounding this pressure is China’s powerful President Xi Jinping, who calls on Chinese media—which is almost completely controlled by the government with very few exceptions—to “tell China’s story well.”

“The growing influence of China [is] taking its toll on Hong Kong media independence,” says Chris Yeung, chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA), a trade union for journalists.

Ownership is one of the main issues in Hong Kong media. In Hong Kong, two papers are owned by the Chinese Communist Party. Others are owned by China-friendly businessmen, including the South China Morning Post (SCMP), Hong Kong’s flagship paper, which was acquired in 2015 by Alibaba Group, co-founded by China’s richest man, Jack Ma. Mainland Chinese investments have stakes in 35 percent of Hong Kong media outlets, according to 2017 HKJA figures. That number rises to about 70 percent for the publishing industry. According to the annual survey commissioned by the HKJA, one in five journalists reported earlier this year that they have come under pressure by higher-ups regarding coverage related to Hong Kong independence. Eighty-one percent of the approximately 500 journalists responding said press freedom in Hong Kong had worsened compared to a year ago. Advertisers are also pressured out of papers carrying coverage unfavorable to the Communist Party. According to Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong has fallen from 58 in 2013 to 73 in 2019 on the World Press Freedom Index.

On Oct. 4, the government invoked an emergency, colonial era law to ban face masks in efforts to curb the escalating unrest. The legislation gives the government sweeping powers which could allow it to censor media, control transport, and impose curfews. A top advisor has said the government would not rule out a ban on the internet.

As outlets face increasing restrictions, the independent press is standing firm and banking on public support for survival

In recent years, media pressure has escalated to blatant attacks. In 2014, Kevin Lau, former editor-in-chief of Hong Kong daily newspaper Ming Pao, was stabbed several times in a knife attack by two alleged triads, a local crime syndicate with a long history of political involvement. In 2015, five Hong Kong book publishers disappeared and reemerged detained in mainland China. In 2018, Hong Kong authorities denied former Asia editor of the Financial Times Victor Mallet a work visa renewal after he hosted a panel for an independence activist at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club.

“We often talk about a drip drip slow erosion,” says Grundy. “We need to put these analogies to bed because it’s happening at a much more accelerated rate.”

Gwyneth Ho doesn’t really remember when the mob attacked her. For the minute by minute, the Stand News reporter needs to reference a video she took while livestreaming on the night of July 21, when a mob of white-shirted men ambushed Hong Kong’s rural Yuen Long metro station and indiscriminately attacked people with sticks and metal bars, injuring at least 45, herself included. Ho suffered a concussion, four stitches in her right shoulder, and a back injury.

“I could do nothing but scream,” Ho recounts. “A protester protected me with his body.”

The video went viral, drawing over 4.7 million views to date, and sent shockwaves through Hong Kong. Up until this point, tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray had already become regular features of anti-government protests. (As of October 1, police had fired more than 4,500 rounds of tear gas and more than 2,000 projectiles, and arrested more than 2,000 people between the ages of 12 and 83, according to the police.) But this incident marked a bloody and horrific turning point that laid bare to the thousands tuning in the importance—and dangers—of frontline journalism.

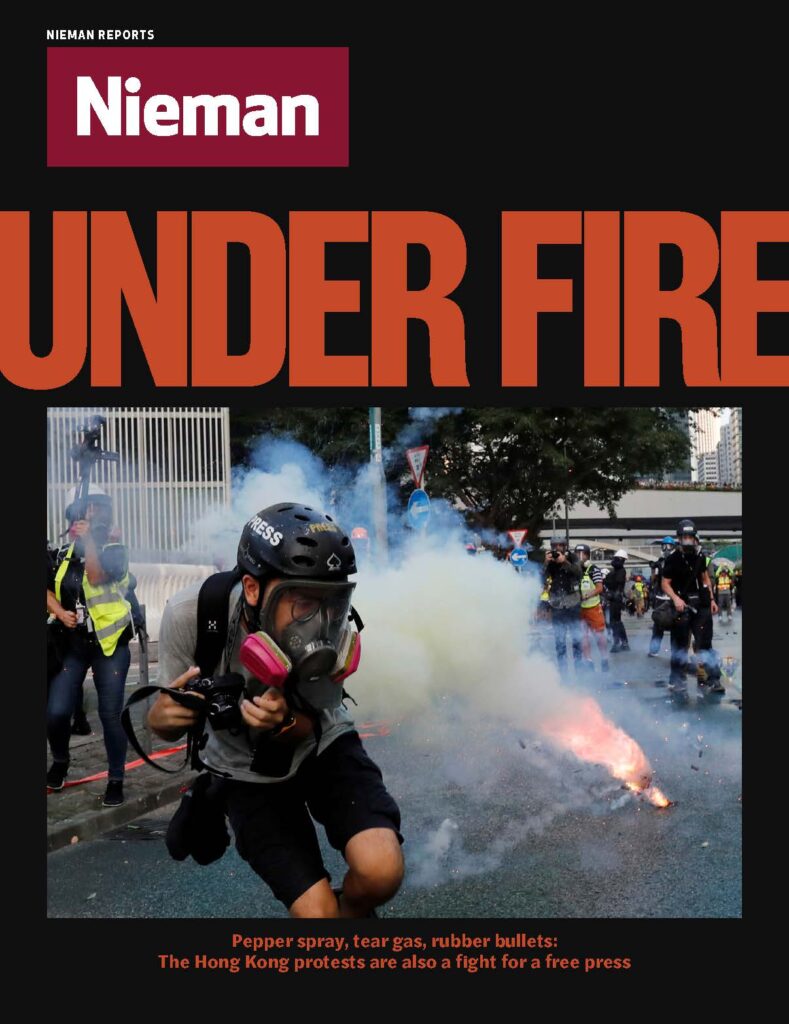

At a September police briefing, the press protested the police’s heavy-handedness by attending in full protective gear

Stand News is a key frontliner. Founded in 2014 as the reiteration of its defunct predecessor House News, the Chinese-language nonprofit outlet was struggling financially. But since July, it has raised more than $255,000 and expanded from 14 to 20 full-time staff, according to editor Pui-kuen Chung. Stand News’ popularity has swelled in part for its reliable Facebook Live streams from the front line. The tool has been around since 2015, but for outlets strapped for resources like Stand News, it’s become an indispensable way to keep up with ever-shifting protests.

“This movement makes it easier for independent media to survive because so many people are … realizing that supporting media is important,” says Ho. “They know we’re under heavy pressure.”

A main source of that pressure is the police, whose use of force against media has escalated over the summer. Police regularly accuse frontline reporters of bias or only filming violence from the police, not protesters. Police shout verbal abuse, calling journalists “cockroaches” or “fake reporters.” They use physical obstruction, floodlights, and strobe lights to prevent journalists from filming arrests or other clearance operations. While some incidents are a matter of getting caught in the crossfire between police and protesters, police are increasingly targeting identifiable journalists with pepper spray, tear gas, and rubber bullets. Some have been pushed or hit. According to the International Federation of Journalists, at least 53 media violations have occurred since June 10.

At a September police briefing, the press protested the police’s heavy-handedness by attending in full protective gear.

On October 3, HKJA, represented by human rights law firm Vidler & Co. Solicitors, the same firm representing Veby Mega Indah, the Indonesian journalist blinded in one eye with a police projectile, filed for judicial review against Hong Kong’s Commissioner of Police for obstructing press freedom and subjecting journalists to “unnecessary and excessive force.”

“Police respect press freedom and the right of the media to report,” Hong Kong Police said in a statement to Nieman Reports. “Furthermore, the Police also understand the interest of the media to film Police work. The Police have maintained communication with media organizations so that both parties have a mutual understanding of their work. There is no change to this process, which can continue on the basis of mutual respect.”

Deliberate attacks also occur among pro-China rallies and mobs. In late August, pro-government supporters rallied around the headquarters of Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), a public broadcaster. Though an arm of the government, RTHK earns high approval ratings for its independence—so much so these ralliers called for “no more anti-government messages” and said RTHK “should represent the voice of the government,” SCMP reports. They attacked reporters covering the scene and called them “black reporters” (a reference to the “black hands” criticism China uses to blame foreign forces for fomenting unrest). Physical assaults happen frequently when protests unfold in pro-Beijing neighborhoods.

Generally, protesters are amicable toward the press, as they rely on media for international attention. But fears of government surveillance and identity exposure have created an atmosphere of paranoia. Protesters rarely give real names and are so protective of their faces that HKFP once received hundreds of messages of protest after posting a photo of a protester during the storming of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. During an airport occupation in mid-August, protesters beat and zip-tied two mainland men on suspicion of being undercover agents. One was later revealed to be a journalist with the Global Times, a Chinese state newspaper.

Every week, Tom Grundy sits down in an editorial meeting with his team and thinks: “How can we do the maximum for the minimum?”

With such limited resources and relentless news, HKFP needs to be savvy. That means free online tools, long hours, and a lot of teamwork. Long-term sustainability is key. A groundswell of financial support has allowed them to make a promo video, hire freelancers to assist with coverage, buy protective gear, and seek a journalist to cover China. But beyond that, with just four people, “we are not in a position to experiment really,” says Grundy.

Instead, they hone what they know: crowdfunding.

And it works. Since the protests began, HKFP’s traffic has leapt from 500,000 to 1 million to 4.5 million pageviews per month. Mid-summer, it exceeded the 2019 fundraising goal by 40 percent, raising more than $233,000 from 2,312 people, enough to secure operations for the year. Most donations came from readers in Hong Kong, but also in Canada, Australia, the U.K., U.S., France, Taiwan, Singapore, and mainland China. HKFP’s monthly patrons leapt from 124 to 531.

“The big barrier for media is to get people to pay up … and these logistical barriers,” says Grundy.

It took HKFP four years to overcome Hong Kong’s lagging digital payment infrastructure relative to other markets in the region. It’s technical and unsexy, but these barriers can cost a small operation 5-10 percent to third-party sites. “It’s just not a financially sophisticated online market, and that impacts everything,” says Ross Settles, a media business veteran and adjunct professor at JMSC. “It’s not that people don’t want to pay. It’s a hassle to pay.”

So the Hong Kong Free Press is building its own system. This year HKFP won a $78,400 Google News Initiative grant to create an open source funding platform for small newsrooms to help build reader membership and enable easy donations. This is especially important for newsrooms in Asia that are often more susceptible to political and commercial pressures.

“Some might wonder why we’re setting up competition,” says Grundy. “But this is something we’re doing for the industry.”

Even as subscription models free news outlets from censorship through commercial pressure, political pressure is resurfacing in a bitter information war online

Initium Media’s transition to subscriptions was not smooth. Launched in 2015, Initium is a Chinese-language digital news outlet known for its long-form features covering Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China. It employs about 40 people with offices in Hong Kong and Taipei. When a cash flow shortage forced a swap to the subscription model in 2017, Initium had to cut 70 percent of its staff. The site put up a paywall for in-depth content, leaving a big question: Would people actually pay?

“Chinese readers do not have the habit of supporting digital media,” says Xiaotong Xu, former audience development manager at Initium. To figure out how to make it work, Xu broke down the barrier between the newsroom and marketing. She insisted on sitting in on editorial meetings to act as the mediator between the readers and the editors. “Customer service [people] think it’s not important or related, but it is,” says Xu. “They are willing to pay, but they really need to see you’re unique.”

That means playing to Initium’s strength. For a publication that specializes in in-depth reporting and features, keeping up with the protests has been difficult. They don’t have the manpower and their livestreams can’t compete with Stand News. While they’ve added some news elements to their coverage, they’re playing the long game, keeping their sights set on the wider content and readership possibilities in China, Taiwan, and the overseas Chinese markets.

It worked. Now, 97 percent of Initium’s revenue comes from 40,000 subscribers. The rest comes from advertisements. This covers 60-70 percent of their costs, while the rest comes from their founding investor, a mainland-born lawyer named Will Cai who was educated in the U.S. and lives in Hong Kong. Says Xu, “It’s not just surviving, it’s thriving.”

“No need to rely on commercial advertisements means the media could be more independent and focus on its readers,” says executive editor Chih-te Lee. Political pressures do not concern him. “[Chinese Communist Party (CPC) officials] are not subscribers,” says Lee. “I hope they will be. Then they can be critical.”

“Protesters. ISIS fighters. What’s the difference?”

“Cockroach soldiers”

“Things the Yellow Media won’t tell you. When there is cooperation between thugs and black journalists. What you see is not news!”

In many ways, the fight for Hong Kong is also a fight for a free press

Even as subscription models free news outlets from censorship through commercial pressure, political pressure is resurfacing in a bitter information war online. Above are just a few posts from China-based accounts removed by Facebook, which, along with Twitter and YouTube, purged their platforms—each of which is banned in China—of accounts spreading disinformation about the Hong Kong protests. Twitter has identified approximately 200,000 in connection to what it described as a “significant state-backed information operation … deliberately and specifically attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong.”

China’s propaganda machine also appears to be on a mission to discredit publications and journalists. In an article on Chinese social media site Weibo, Chinese Communist Party-mouthpiece People’s Daily attacked the HKJA for being “filthy and plagued” and holding a “double standard.” Chinese state media labeled publications as “yellow media”—the color of the pro-democracy camp; blue is pro-China— including Apple Daily, Stand News, and CitizenNews. CCP-backed media have also tried to paint the protests as orchestrated by foreign forces, naming Twitter bloggers and New York Times employees as “foreign commanders.”

Chinese media in Hong Kong “is subjected to much more pressure than English media,” says Daisy Li, editor-in-chief of CitizenNews, a Chinese-language independent news site founded by 10 senior journalists in defense of press freedom in 2017. “They ultimately worry it will bleed over to mainland China.”

Like most Hong Kong media, CitizenNews is banned on the mainland. CitizenNews protects itself from influence through crowdfunding and subscriptions. Like any start-up, the main issue is money. But they do what they can. They offer newsletters for their 1,600 paid subscribers, focus on in-depth news, analysis, and human interest stories, and re-share other livestreams to stay on stop of breaking news.

So far, propaganda has had little measurable impact on CitizenNews. In fact its readership had jumped from 6.5 million pageviews per year in 2018 to 8.5 million by August. But the damage is not insignificant. “The purpose is really to confuse the public so that they will lose trust in what the media says, and that’s quite damaging in the long run,” says Yeung of HKJA, who is also chief writer at CitizenNews. “People do realize that what they see might not be the truth. So there are a little more doubts of accuracy and authenticity of the media.”

Chinese trolls also personally target Hong Kong journalists. Eric Cheung, a freelance journalist, said he regularly receives direct messages on social media shaming him for not covering the protesters accurately and being a “Chinese traitor.” “These people feel like if you’re Chinese, you should support China,” says Cheung. Laurel Chor, a freelance photojournalist, had to contact Instagram after pro-Beijing trolls inundated her account with thousands of “vulgar and sexist” comments.

Disinformation plagues both sides. Protesters are also heavily pushing their own narrative, from masked orchestra anthems to “Chinazi” posters—imagery that draws a parallel between Nazi Germany and Communist China. After police revised the number of people injured in a highly controversial metro station storming, unsubstantiated rumors circulated that three people had died. However, protest propaganda does not target journalists.

“False news doesn’t necessarily divide society,” says disinformation expert Masato Kajimoto, an assistant professor at the JMSC. “It’s a symptom of a polarized society, not the cause of polarization itself.”

The polarization puts journalists in a tricky position. In many ways, the fight for Hong Kong is also a fight for a free press. But that fight cannot bleed into the reporting, especially as a free press already carries an inherent bias in the eyes of China. The protest movement has drawn broad support from society, but when reporting on a compelling, existential story in a city that many reporters are from, objectivity is essential.

“For journalists, maintaining journalistic independence in an intense situation of conflict, in a very fast changing news cycle,” says Ying Chan of JMSC, “that’s the challenge now.”

“We look at things from Hong Kong people’s point of view,” says Li of CitizenNews. “In that sense, what we treasure is freedom of speech, an independent judiciary, efficient and non-corrupted administration … That’s what we are proud of. So in that point of view, the way we report certainly would be different from the sovereign state of China.”

In mainland China, propaganda has effectively whipped up public outcry and nationalism. But in Hong Kong and beyond, it does not appear to be working.

“The Hong Kong internet users are quite smart. Anything written in simplified Chinese, they immediately dismiss as the 50 cent army,” says Kajimoto referring to hundreds of thousands of people paid by the Chinese government to write fake comments. The same goes for the English-speaking audience, as Beijing seems to employ the same strategies that work in Chinese propaganda. Chinese state media is “not as sophisticated as the Russians,” says Kajimoto. “It’s clearly not working in a free press world because we know better than that.”

What happens when the protests die down? For indepen- dent media, it’s an uncomfortable and uncertain future

“It will happen … I don’t know how and when,” says Li about a crackdown on free press. “But there must be some way we can counter. That’s the belief we had well before the protests. After the last few months, I’m more confident we can find ways to counter it.”

What happens when the protests die down? For independent media, it’s an uncomfortable and uncertain future. The protests are a historic turning point, both for the city and the press. But when the news cycle moves on, the fear is being forgotten.

“When that spotlight fades, that is when I get more concerned,” says Grundy. “What’s going to happen with surveillance and free press, because Beijing will want to make sure this doesn’t happen again.” Coverage will slow, mass arrests will turn into protracted but critical court cases, and questions of how to make space in the cage will resurface once more.

“Things are only worsening,” says Grundy. But no matter how things pan out in the coming years, “we built something to weather any storm. We can run [the Hong Kong Free Press] anywhere in the world.”