For a little over a year, I’ve served as YouTube’s news and political director — perhaps a perplexing title in the eyes of many journalists. Such wonderment might be expected since YouTube gained its early notoriety as a place with videos of dogs on skateboards or kids falling off of trampolines. But these days, in the 10 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute of every day (yes — every minute of every day), an increasing amount of the content is news and political video. And with YouTube’s global reach and ease of use, it’s changing the way that politics — and its coverage — is happening.

Each of the 16 one-time presidential candidates had YouTube channels; seven announced their candidacies on YouTube. Their staffs uploaded thousands of videos that were viewed tens of millions of times. By early March of this year, the Obama campaign was uploading two to three videos to YouTube every day. And thousands of advocacy groups and nonprofit organizations use YouTube to get their election messages into the conversation. For us, the most exciting aspect is that ordinary people continue to use YouTube to distribute their own political content; these range from “gotcha” videos they’ve taken at campaign rallies to questions for the candidates, from homemade political commercials to video mash-ups of mainstream media coverage.

What this means is that average citizens are able to fuel a new meritocracy for political coverage, one unburdened by the gatekeeping “middleman.” Another way of putting it is that YouTube is now the world’s largest town hall for political discussion, where voters connect with candidates — and the news media — in ways that were never before possible.

In this new media environment, politics is no longer bound by traditional barriers of time and space. It doesn’t matter what time it is, or where someone is located — as long as they have the means to connect through the Web, they can engage in the discussion. This was highlighted in a pair of presidential debates we produced with CNN during this election cycle during which voters asked questions of the candidates via YouTube videos they’d submitted online. In many ways, those events simply brought to the attention of a wider audience the sort of exchanges that take place on YouTube all the time. Here are a few examples:

- Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney’s campaign asked supporters to make political commercials for his campaign. What he got was hundreds of free online ads after they were put on the Web.

- Hundreds of thousands of voters responded to Senator Clinton’s request for them to vote for her campaign theme song on YouTube.

- Senator Barack Obama reached almost five million voters on YouTube with a 37-minute clip of his speech on race in America, shattering the notion that only short, lowbrow clips bubble to the top of the Internet’s political ecosystem.

Senator John Edwards smiles as his wife, Elizabeth, buys a shirt for their son, Jack, at Jack’s Café during a campaign stop in Charleston, South Carolina. April 2007. Photo by Grace Beahm/The Post and Courier.

News Organizations and YouTube

Just because candidates and voters find all sorts of ways to connect directly on YouTube does not mean there isn’t room for the mainstream media, too. In fact, many news organizations have launched YouTube channels, including The Associated Press, The New York Times, the BBC, CBS, and The Wall Street Journal.

Why would a mainstream media company upload their news content to YouTube?

Simply put, it’s where eyeballs are going. Research from the Pew Internet & American Life project found that 37 percent of adult Internet users have watched online video news, and well over half of online adults have used the Internet to watch video of any kind. Each day on YouTube hundreds of millions of videos are viewed at the same time that television viewership is decreasing in many markets. If a mainstream news organization wants its political reporting seen, YouTube offers visibility without a cost. The ones that have been doing this for a while rely on a strategy of building audiences on YouTube and then trying to drive viewers back to their Web sites for a deeper dive into the content. And these organizations can earn revenue as well by running ads against their video content on YouTube.

In many ways, YouTube’s news ecosystem has the potential to offer much more to a traditional media outlet. Here are some examples:

- Interactivity: YouTube provides an automatic focus group for news content. How? YouTube wasn’t built as merely a “series of tubes” to distribute online video. It is also an interactive platform. Users comment on, reply to, rank and share videos with one another and form communities around content that they like. If news organizations want to see how a particular piece of content will resonate with audiences, they have an automatic focus group waiting on YouTube. And that focus group isn’t just young people: 20 percent of YouTube users are over age 55 — which is the same percentage that is under 18. This means the YouTube audience roughly mirrors the national population.

- Partner With Audiences: YouTube provides news media organizations new ways to engage with audiences and involve them in the programming. Modeled on the presidential debates we cohosted last year, YouTube has created similar partnerships, such as one with the BBC around the mayoral election in London and with a large public broadcaster in Spain for their recent presidential election. Also on the campaign trail, we worked along with Hearst affiliate WMUR-TV in New Hampshire to solicit videos from voters during that primary. Hundreds of videos flooded in from across the state. The best were broadcast on that TV station, which highlighted this symbiotic relationship: On the Web, online video bubbles the more interesting content to the top and then TV amplifies it on a new scale. We did similar arrangements with news organizations in Iowa, Pennsylvania and on Super Tuesday, as news organizations leveraged the power of voter-generated content. What the news organizations discover is that they gain audience share by offering a level of audience engagement — with opportunities for active as well as passive experiences.

For news media organizations, audience engagement is much easier to achieve by using platforms like YouTube than it is to do on their own. And we just made it easier: Our open API (application programming interface), nicknamed “YouTube Everywhere” — just launched a few months ago — allows other companies to integrate our upload functionality into their online platforms. It’s like having a mini YouTube on your Web site and, once it’s there, news organizations can encourage — and publish — video responses and comments on the reporting they do.

Finally, reporters use YouTube as source material for their stories. With hundreds of thousands of video cameras in use today, there is a much greater chance than ever before that events will be captured — by someone — as they unfold. No need for driving the satellite truck to the scene if someone is already there and sending in video of the event via their cell phone.

It’s at such intersections of new and old media that YouTube demonstrates its value. It could be argued, in fact, that the YouTube platform is the new frontier in newsgathering. On the election trail, virtually every appearance by every candidate is captured on video — by someone — and that means the issues being talked about are covered more robustly by more people who can steer the public discussion in new ways. The phenomenon is, of course, global, as we witnessed last fall in Burma (Myanmar) after the government shut down news media outlets during waves of civic protests. In time, YouTube was the only way to track the violence being exercised by the government on monks who’d taken to the streets. Videos of this were seen worldwide on YouTube, creating global awareness of this situation — even in the absence of journalists on the scene.

Citizen journalism on YouTube — and other Internet sources — is often criticized because it is produced by amateurs and therefore lacks a degree of trustworthiness. Critics add that because platforms like YouTube are fragmenting today’s media environment, traditional newsrooms are being depleted of journalists, and thus the denominator for quality news coverage is getting lower and lower. I share this concern about what is happening in the news media today, but I think there are a couple of things worth remembering when it comes to news content on YouTube.

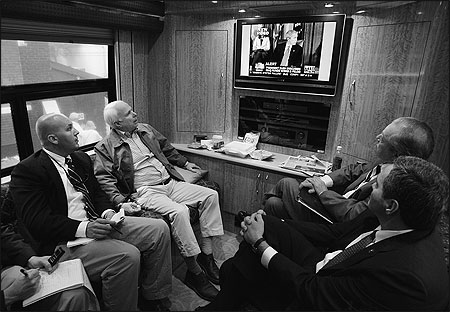

While traveling on his campaign bus, Senator John McCain watches President George W. Bush on television as a reporter records his reaction. Photo by Alan Hawes/The Post and Courier.

Trusting What We See

When it comes to determining the trustworthiness of news content on YouTube, it’s important to have some context. People tend to know what they’re getting on YouTube, since content is clearly labeled by username as to where it originated. A viewer knows if the video they’re watching is coming from “jellybean109” or “thenewyorktimes.” Users also know that YouTube is an open platform and that no one verifies the truth of content better than the consumer. The wisdom of the crowd on YouTube is far more likely to pick apart a shoddy piece of “journalism” than it is to elevate something that is simply untrue. In fact, because video is ubiquitous and so much more revealing and compelling than text, YouTube can provide a critical fact-checking platform in today’s media environment. And in some ways, it offers a backstop for accuracy since a journalist can’t afford to get the story wrong; if they do, it’s likely that someone else who was there got it right — and posted it to YouTube.

Scrutiny cuts both ways. Journalists are needed today for the work they do as much as they ever have been. While the wisdom of crowds might provide a new form of fact checking, and the ubiquity of technology might provide a more robust view of the news, citizens desperately need the Fourth Estate to provide depth, context and analysis that only comes with experience and the sharpening of the craft. Without the work of journalists, then citizens — the electorate — lose a critical voice in the process of civic decision-making.

This is the media ecosystem in which we live in this election cycle. Candidates and voters speak directly to one another, unfiltered. News organizations use the Internet to connect with and leverage audiences in new ways. Activists, issue groups, campaigns and voters all advocate for, learn about, and discuss issues on the same level platform. YouTube has become a major force in this new media environment by offering new opportunities and new challenges. For those who have embraced them — and their numbers grow rapidly every day — the opportunity to influence the discussion is great. For those who haven’t, they ignore the opportunity at their own peril.

Steve Grove is the news and political director at YouTube.