From journalistic pariah to savior of the news industry, blogs have undergone an enormous transformation in recent years. As a journalist and a blogger, I was curious to see how this transformation from blogophobia to blogophilia was affecting journalism. Was the hype surrounding the potential of blogs to transform our craft being realized—or were journalists simply treating their blogs as another “channel” into which to plough content?

RELATED WEB LINK

Read more about the findings of this online survey on the author’s blog. »Earlier this year I distributed an online survey to blogging journalists to get a feel for the lie of the land. The response was incredible—coming from 200 journalists from 30 countries, representing newspapers and magazines, television and radio, online-only and freelancers. United States and United Kingdom respondents dominated, but every continent (except Antarctica) was represented.

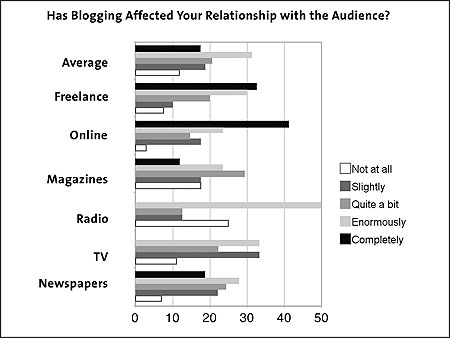

As I pored over the results, I was surprised at just how much these journalists felt their work had been changed by the simple act of blogging. I had expected some effect on their relationship with the “former audience,” but what surprised me most was when more than half of the blogging journalists said this relationship had been “enormously” or “completely” transformed. At the same time, when I might have anticipated that some aspects of the journalistic process to be affected, I found, instead, consistency in responses I received. This included in areas ranging from how journalists generated story ideas and leads to newsgathering and news production and even what happens after publication or broadcast. In each instance, the majority of journalists told stories of change.

So the headline is: Blogging is changing journalism—at least for those journalists who blog. But alongside this conclusion resides a collection of more interesting findings.

Cutting Out the Middlemen

In generating story ideas, blogging journalists don’t need someone to tell them who the readers are and what they want: They already know, because the readers are on their blogs, telling them who they are and what they’re curious about. In this new blogging relationship, editors are the middlemen being cut out.

The role of official sources—such as public relations spokespeople and firms—were also being diminished, as sources for stories broadened. Story leads now come through the comments or through private communication initiated via the blog. And once they are pursuing a story, some journalists use the blog to “put the call out” for information and sources—and rely on the transparency of their reporting process to push official sources to reply. One respondent wrote:

|

On hot-button stories where our readers are asking a lot of questions, we post updates every time we make a phone call. For example, [a company] declared bankruptcy, and the new owner wouldn’t take the previous owner’s gift cards. Our readers were peeved and hounding us to do something. The corporate folks weren’t saying anything, so we didn’t have any new information to report. Because we didn’t have any new info, we didn’t write anything in the paper. But on our blog, we would post updates at least daily to tell people when we left a message and if we had heard back yet. We eventually scored an interview with the new CEO and posted it in its entirety on our site. Another reporter saw it and called us. We swapped info. Our readers also post links to other stories on the topic from other news orgs. |

In some examples, this collaboration becomes a form of crowdsourcing. But for others the pressure to publish meant more reliance on rumors and less rigorous research, with the onus placed on blog readers to clarify and fact check.

Swifter, Deeper, Stronger

In production, blogging journalists felt they worked more quickly, breaking stories on their blogs before following up online and in print or broadcast. They also write shorter, more tightly edited pieces, not just for blogs but also for print and broadcast. Reporters said they write more informally than before, while using the blog as a space to publish material that didn’t “fit” the formats of print and broadcast. And journalists link to other stories when time or space constraints mean they are unable to report in full—what Jeff Jarvis called on his blog, BuzzMachine, “Covering what you do best and linking to the rest.”

After publication or broadcast, blogging journalists are less inclined to discard a story completely; stories had “more legs.” Errors and updates get highlighted by readers and fixed. The permanence of the Web means stories are always “live.” In the words of two journalist bloggers:

|

The audience remains able to comment on the content and regularly provides information which updates it. The reporter then has the opportunity to revisit the subject, creating a great “off diary” print story (loved by news editors everywhere). Well, you never finish, do you? You write something that may or may not spark a conversation, and you’ve got to be ready for that conversation even if it happens months later. |

This importance of distribution emerged as a significant change, as journalists spoke of forwarding links, posting updates on Twitter, and using RSS.

Interactivity and “conversation” were frequently mentioned. As one journalist blogger let me know:

|

I cover more than 30 countries. The reaction of people who live in a place tells me a lot about the issues I am writing about. My blog seems to generate arguments, which at least help me understand a story more. |

An Uneven Picture

Despite these similar trends, the picture was not the same everywhere. Freelance or online-only journalists were more likely to say that their work had been transformed “enormously” or “completely.” In contrast, no journalist employed by the television or radio industries felt that blogging had “completely” changed any aspect of their work.

Similarly, sport journalists reported less change in their work than any other journalists. Media, technology, finance and arts and culture journalists were more likely than others to say that blogging had changed their processes “enormously” or “completely.”

A third of the respondents only started to blog in the past year, so my suspicion is that there remains room for more change. Clearly, we are only at the beginning, as the news industry faces one of the most significant transformations in its history.

Paul Bradshaw is a senior lecturer in online journalism and magazines at Birmingham City University’s School of Media in the United Kingdom. He is also the publisher of Online Journalism Blog and a contributor to Poynter’s E-Media Tidbits (http://onlinejournalismblog.com).