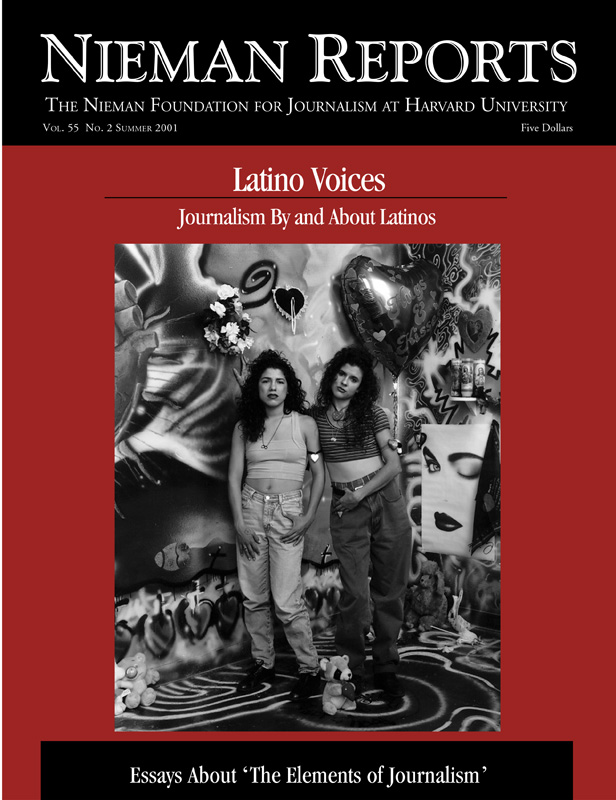

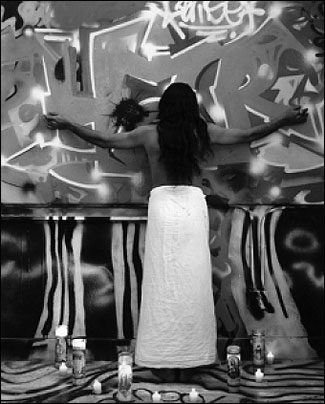

“Jesus’s Carburetor Repair.” Photo by Delilah Montoya.

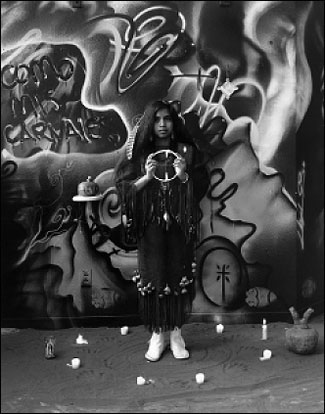

My photographic essay, “Sagrado Corazón/Sacred Heart,” is an exploration of a cultural icon that reveals the syncretic aspects of my Chicano heritage. The Baroque Sacred Heart in the Americas is an icon that resulted from an encounter between the Spanish and indigenous peoples. It is traditionally positioned in conjunction with a portrait of Jesus or Mary.

To bring this collection of photographic images together, I created portraits of Chicanos posed in constructed environments. To find an environment to represent our cultural perspective, I invited aerosol artists from our community to spray paint the walls. I then used this environment as a backdrop for the series, and these different spaces were installed in my studio to give an atmosphere for each sitter to enter. Each sitter then contributed by illustrating a facet of the Sacred Heart and by bringing artwork or objects that were placed in the installations. The environments constructed in my studio, combined with the sitters’ particular additions, reveal a collective interpretation of the Sagrado Corazón.

The Sacred Heart’s significance as a cultural icon lies in its expression of syncretism found at the intersection of the American Indian and Spanish European cultures. Expressing the European concept of passion as well as the Nahua [Aztec] understanding of the soul, it is simultaneously the Nahua sacrificial heart and Mary’s heart, in turn reflecting the heart of Christ. The Sagrado Corazón expresses a vision shared between two cultures.

Within the Chicano community, the Sacred Heart functions as a religious icon as well as a pop reproduction. The heart is tattooed on the arms of working class youth, often next to an idealized woman, or it is drawn on brilliant white cotton T-shirts. It is transformed into holograms on plastic clocks. Or the Sacred Heart can be painted on glass jars containing candles that burn on an altar constructed, perhaps, by an anxious mother waiting for her child’s safe return from war.

The Sagrado Corazón is generally represented within the context of a portrait and used to express the heart as a cultural icon. Because of this, I wanted the community that venerates this icon to be a part of its portrayal. In my photographic portraits, this happens. In the same manner that the Sacred Heart of Mary and Jesus expresses an aspect of the Sagrado Corazón, each community member reveals in this portrait a life-defining interest.

In one photograph, I wanted to create an image featuring an auto part that looked like a heart. So I invited Apolinar “Polo” García, my trusted mechanic and a respected resident of the San Jose barrio, to sit for a portrait. Initially I wanted to photograph him holding this metallic auto part as though revealing his heart. In explaining the concept to Polo, I presented the heart-shaped part and commented on the resemblance of one of the pipes to an aorta.

He simply raised his eyes and said, “No, Delilah, that is not the heart of the engine.” He grabbed from his workbench a carburetor and lifting it to my face asserted, “This is the heart of an engine.” Corrected, I proceeded to reorganize the shoot. Ultimately, I called his portrait “Jesus’s Carburetor Repair,” for I believe this image operates as a metaphor for Jesus repairing hearts.

Culture shapes reality, and this helps us to acknowledge that the reality being addressed is filtered through the photographer’s way of seeing. Yet there remains a question of paramount importance: How is the community’s reality being represented?

As a photographic printmaker, my approach in representing the Sagrado Corazón as a cultural icon was through collaboration with members of my community. This alliance brought out our creative and energetic interdependence. This made it easy for me to sign not only my name on the images, but to also have the artists—the sitters—who contributed to the project do so as well. Of greater interest to me, however, was the collective awareness of how this project validated the Sagrado Corazón as an intricate part of our conscience.

Photos by Delilah Montoya.©

“Curanderisma.”

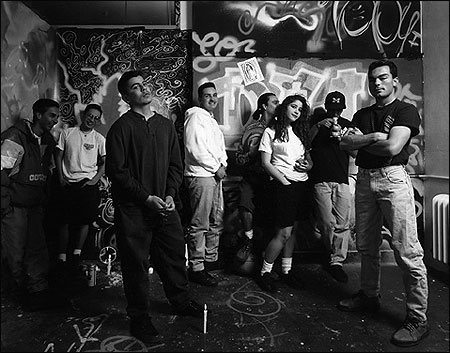

“Los Jovenes.”

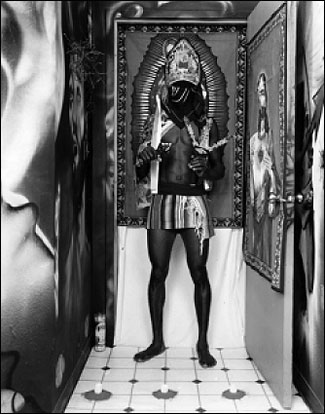

“El Matachin/Moro.”

“God’s Gift.”

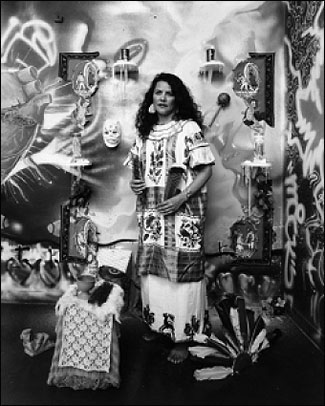

“La Genizara.”

Delilah Montoya is a photographic printmaker whose work has appeared in the journal Nueva Luz, the exhibition “Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965-1985,” and the magazine ArtNexus. The work resides in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Smithsonian Institute, and Stanford University Libraries collections. Currently, she lives and works in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and has completed visiting artist positions at Smith and Hampshire Colleges in Massachusetts.