War zones test only a part of photojournalists’ courage. It’s the noisy part, filled with an odd mixture of bravado, determination and hope, layered onto an intense focus on the day-to-day job of bearing witness to brutality that is impossible to comprehend. Enduring such danger is one reliable way for photographers to build their reputations and get their pictures used. Only after I left the foreign battlefields and returned to the United States did I discover the quiet part of courage in what it is I try to do.

As my early mentor, Donald Greenhaus, told me, for the photographer willing to chance rejection, and possibly ridicule, from those who hold the power to accept or reject his work, the opportunities are boundless. To bear witness to what isn’t shown with the purpose of revealing an aspect of life no one expects to see is the challenge I took on. In an urban environment linked in people’s minds to violence, there can be courage in a photographer’s willingness to reject those anticipated images in favor of showing some of the more affirming, unexpected moments of youngsters’ daily life.

Easier to sell into a marketplace hungry for verification of what already is known about poverty and racism are the guns and blood, the street corner hangouts, and the swollen bellies of teenage girls. More enlightening, however, might be visual evocations of those quieter moments when what is revealed becomes worth knowing.

Beirut 1984: John Hoagland, Newsweek magazine staff photographer, Rick Tompkins, Associated Press stringer (with the camera to his eye), and I were taking photos of the Muslim revolt from a hotel window. This was my second tour covering the situation in Lebanon for Magnum Photos. We were shooting from the window because the fighting was too out of control and fierce on the street. Hoagland was sent to Beirut for a short break from El Salvador, where he had been covering the civil war. It was deemed unsafe for him to continue working there because death squads had threatened him. Beirut was relatively quiet and not seen as dangerous as El Salvador. After his work in Beirut, Hoagland returned to El Salvador where, on assignment, he was caught in crossfire and killed.

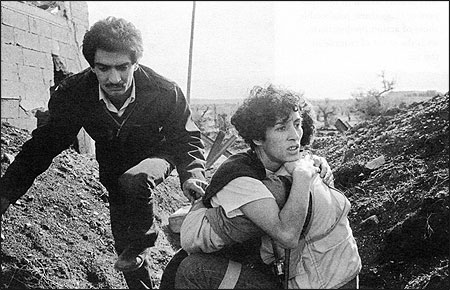

Northern Lebanon 1983: I remember another especially ugly day during internecine fighting in the Beddawi refugee camp. I was running for my life down a dusty road, moving with three other photojournalists away from our rocket-damaged car and the incoming shelling, which came down as if it were rain. I thought to myself, "I could be in San Francisco looking at the ocean and yet here I am preparing to die gracefully." Things started to unravel quickly, but I managed to take this photograph of my colleagues (the driver is to the left) after diving into a ditch as the shelling and the fighting raged around us.

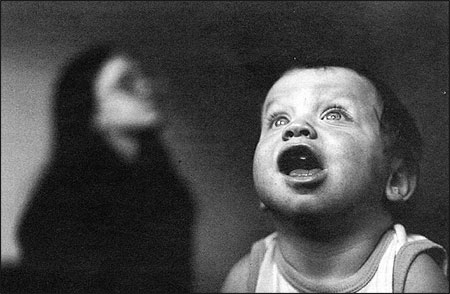

Seattle, Washington, the 1990’s: This photograph of a mother and her baby appeared in an issue of People magazine that was dedicated to an in-depth coverage of teenage pregnancy. Showing them together in this way illuminates the experience from a perspective that rarely is acknowledged in our national conversation about this emotional issue.

Harlem, New York, 2004: This photograph of young black men hanging out on a stoop was taken in late summer for a project I’ve been working on for a few years addressing what life looks like to those growing up in Harlem today. This kind of image isn’t usually found in newspapers or magazines; predictable shots of action predominate, with the scent of trouble in the air.

Photos and captions by Eli Reed.

Eli Reed, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, is a Magnum photojournalist and professor at the University of Texas at Austin. In his long career, he has covered civil wars and other events in El Salvador, Beirut, Haiti and Panama, as well as work documenting the black experience in America and Africa.