Photo by Alixandra Fazzina/Trolley Photos.

It is nearly two centuries now since human behavior began being captured by cameras and displayed in all manner of frames, pages and screens. As a record of experiences from rapture to catastrophe, photography is one of technology’s greatest gifts to history. What was true when Mathew Brady photographed the Civil War is still true today, as a stream of recent books and exhibits about conflicts in Iraq, Africa and Asia make vividly clear: A gifted eye behind the lens captures life as no other medium possibly can. Over time, the means of securing images and delivering them has evolved to the point of instantaneous transmission. As recently as the Vietnam War, photographs could be wire transmitted, but film reels were flown from Saigon via Hong Kong to New York, giving that first “living room war” a measured quality compared to today’s live footage.

Now, of course, war and everything else can be shown as it happens and replayed incessantly on the Web. We are surrounded by video recorders that convey activity as information, entertainment and protection against crime. More and more, cell phones even in remote areas are also cameras, and events are witnessed at angles inconceivable barely more than a decade ago. Everything everywhere is accessible to a hand-held device. The likelihood, based on the trend, is that in time this process will provide even more quality and range, although it is hard to imagine what could be faster than transmission at digital speeds.

RELATED WEB LINK

“World’s ‘Lost’ Boys Follow Tragic Path of Violence”

– Richard Rodriguez, Online NewsHourAnd yet, for all these advances, there is a case that the most powerful use of photographic imagery remains remarkably close to what it was a century or so ago: The still camera conveying people either posed or candid in ways that impart insight and emotion beyond the settings, even when these are themselves awesome in beauty or horror.

Every generation produces a cadre of photographers who set out to document, in the most revealing ways their skills permit, the unfolding events of the age. This epoch probably can be dated to the end of the cold war, which coincided with the rise of the Internet, an era characterized by the transformation of imagery from the relatively contained canvas of the past to the limitless, and even overwhelming, scope of today. But like the Web in other ways, the outpouring of visuals can be vast without being discriminating, highlighting again the distinctive role played by trained photographers and their editors, a time-honored relationship worth maintaining.

‘Child Soldier’: Haunting Eyes

This entente is on display in an extensive and well-produced catalog for “Child Soldier,” an exhibit at War Photo Limited, a gallery in Dubrovnik, Croatia this fall featuring the work of Jan Grarup in Israel-Palestine, Yannis Kontos with Maoist rebels in Nepal, Alixandra Fazzina, Noel Quidu, and Franco Pagetti in Africa. In his introduction, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, writes, “Delve deeply into the eyes of these children, into the eyes above all else. For there you may see the future gaze of disoriented, disconnected tormented adults, miniature walking time bombs for whom society will struggle to find a place.” Trolley, a leading London-based photography and art book publisher, is featuring the work of Grarup in Darfur, Fazzina in Somalia, and Pagetti on Iraq in separate works scheduled to be released in the coming months and available from booksellers and online retailers.

It is striking that given how much more is now technically possible with imagery, this exhibition and the books again demonstrate the power in the hands of intrepid, artistically gifted photojournalists who travel to trouble and assemble what they find without written commentary. What also comes across are the common elements of conflict. The arrest this summer of Radovan Karadzic revived memories of the 1990’s Balkan wars, barely more than a decade in the past but already consigned to a continuum of mayhem that removes most of the elements of timeliness and makes the images, especially those in black and white, essentially timeless. The passion of the photographers’ work remains distinctive over the generations, but their messages are universal.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are the first American-led ground wars in the digital era. It has been notable, especially as the wars have dragged on, how relatively little has been done with images of American, British and coalition soldiers. The most indelible images from Iraq so far are the snapshots of prisoners in Abu Ghraib and the arrest, trial and execution of Saddam Hussein. In none of these was artistry an issue. Their impact was in shaping the news of the day, rather than revealing the deeper meanings conveyed in conflict photography. Perhaps because so much more imagery is now available, the Pentagon has gone to extra lengths to limit, where possible, pictures of GIs fighting and dying.

Photographs are journalism at its most powerful and, in these wars, the pictures of Iraqis and Afghans have been in keeping with photography’s time-honored tradition of impact; those of Americans, less so.

So the technology that has made imagery more prevalent by no means assures quality and lasting effects or restrains the instinct of authorities to impose controls where they can. Ultimately, we are again reminded, photography is mostly what the people holding the cameras can make of it.

Peter Osnos, who founded PublicAffairs, an independent publishing company, in 1997, was a foreign correspondent and editor for The Washington Post. He writes a weekly column about media, called “The Platform,” for The Century Foundation. In a summer 2008 column entitled, “A Note about Images,” he wrote about related topics.

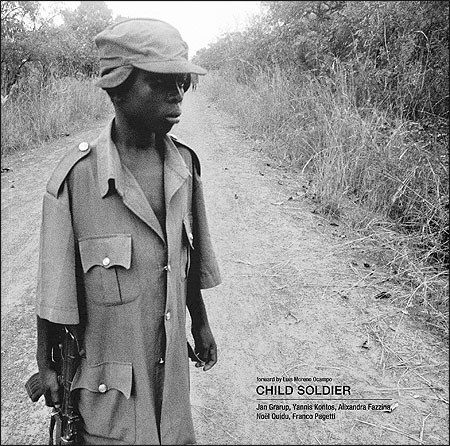

Northern Uganda, 2004—12-year-old Omoding Musami regroups with his militia unit known as the “Arrows” at their base in Asamuk, deep in the bush of northeastern Uganda. Captured by Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels during a Saturday night raid on a Catholic church in Amucu, Omoding was given a gun and forced to fight on the frontline along with a rag-tag unit of other children. [His photograph is on the “Child Soldier” catalog cover on page 79.] Suffering beatings and torture by his commander, he escaped after one month. Having grown up knowing nothing but war, Omoding wanted to continue fighting despite gaining his freedom. Joining one of Uganda’s many Arrow Groups has given him a new family, and he is well respected for his agility and energy when on maneuvers. Photo and caption by Alixandra Fazzina/Trolley Photos.

Kitgum, Northern Uganda, 2003—Having recently escaped from the LRA, three young ex-combatants now spend each night away from their families for fear of reabduction. Joining thousands of other children known as “night commuters,” they spend each night sleeping in the relative safety of Saint Joseph’s Hospital rather than face nighttime attacks from the rebels in their villages. Photo and caption by Alixandra Fazzina/Trolley Photos.

Ramallah, 2002—Marching through the streets, young Palestinian boys of all ages receive training from the Tanzim, the armed wing of the Fatah. Photos and captions by Jan Grarup/Noor.

Ramallah, 2001—Jimaan, the boy in the background, cries from the effects of teargas fired by Israeli soldiers at the City Inn Hotel frontline on the city’s outskirts. Photos and captions by Jan Grarup/Noor.

Ramallah, 2002—After Ramzi’s death, his younger brother took his place at the frontline, even though he promised his father not to. Photos and captions by Jan Grarup/Noor.

Freetown, June 2000—Jonny, a former child soldier with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), remains both physically and mentally scarred, never leaving his room at the recuperation center in Calabatown, a Freetown neighborhood. For many who tried to escape from the RUF, the punishment was to be branded. Photo and caption by Franco Pagetti/VII.

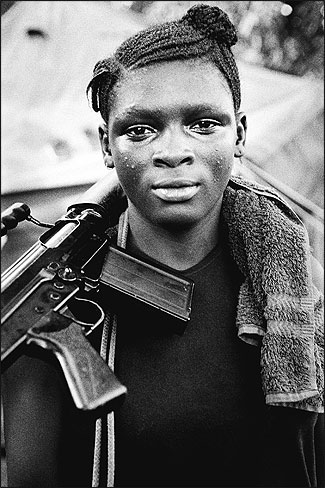

Rogberi Junction, June 2000—A teenaged RUF rebel. The RUF, infamous for their forced recruitment of child soldiers and maiming of civilians, used children and young women as fighters, porters, cooks and sex slaves, or bush-wives. Photo and caption by Franco Pagetti/VII.

Masiaka, June 2000—Near the frontline a child soldier downs his daily “Busta,” gin and drugs, in preparation for a fight against the rebels of the RUF. Photo and caption by Franco Pagetti/VII.