Twenty years ago, there was no network news “business.” The Big Three broadcast television networks—ABC, CBS and NBC—all covered news, but none generally made money doing so. Nor did they expect to turn a profit from news programming. They presented news programming for the prestige it would bring to their network, to satisfy the public-service requirements of Congress and the Federal Communications Commission, and more broadly so that they would be seen as good corporate citizens.

Back then, the networks earned enough money from entertainment programming that they could afford to run their news operations at a loss. And so they did. Former CBS correspondent Marvin Kalb recalls Owner and Chairman William Paley instructing news reporters at a meeting in the early 1960’s that they shouldn’t be concerned about costs. “I have Jack Benny to make money,” he told them.

It is no exaggeration to say that just about everything has changed since then. Today, ABC, CBS and NBC operate in a competitive environment in which most viewers have dozens of channels from which to choose. That has transformed not just TV news but the entire television industry. Those most severely threatened by the way the broadcast business operates are the Big Three. The ABC and CBS networks (now subsumed into larger corporate structures) are losing money, according to Wall Street analysts. NBC’s network profits are also falling sharply. Those who own these networks—Disney (ABC), CBS Inc. with its major stockholder, Mel Karmazin, and General Electric (NBC)—all demand that their news operations make money.

This demand for profit arises not because these owners are greedier than their predecessors were, but because the financial challenges they face are tougher. The TV entertainment business, in particular, has deteriorated because programming costs are rising while, due to more competition, ratings are falling and hit shows are harder to find. All of this leaves the TV entertainment business struggling to find its way. The networks’ entertainment and sports operations are so troubled that news, particularly in prime time, is becoming one of the networks’ most consistently profitable businesses. To some extent, news programs are now looked to as ways to subsidize entertainment and sports offerings—just the reverse of the way things used to be.

…given the current economic climate, how best can journalists respond to these corporate, societal and technological changes and preserve the quality and integrity of news?

What do such changes mean for the practice of journalism at the Big Three? Is this possibly the best of times for network news, since as the news becomes more profitable, its status will rise within the corporation, and with increased status will come a finer product? Or is this a troubled time for network news, as old-fashioned values of public service that once guided news judgment cede ground to business-driven imperatives? Most importantly, given the current economic climate, how best can journalists respond to these corporate, societal and technological changes and preserve the quality and integrity of news?

Network News Still Matters

Because so much has been written recently about the decline of the Big Three and the rise of cable and the Internet, it is worth observing that network news still matters. In turn, what stories the Big Three choose to broadcast and how they tell them also still matters.

During 1998, the three evening newscasts reached a combined average of about 30.4 million viewers in 22 million homes. This represents a reach that is greater than the total circulation of the nation’s 10 largest newspapers. Prime-time news programs connect with even larger audiences. CBS’s “60 Minutes” (Sunday), the industry leader, has attracted an average of 13.4 million homes so far during the 1998-99 TV season. And “60 Minutes” is only one of 14 prime-time, hour-long news shows appearing on the Big Three. No cable program or newspaper has anything approaching that kind of reach. The most popular cable news program, CNN’s “Larry King Live,” is seen by fewer than one million homes on a typical night. The Big Three networks are still, by far, the most commanding voices in American journalism and therefore one of the most important forces in our democracy.

Finding the Formula for Profits

The evolution of network news into a profit-making business unfolded gradually, driven by a series of events dating back more than two decades. The success of “60 Minutes,” which became a Nielsen top 10 program in the 1977-78 season, 10 years after its debut, was an enormously influential factor. To compete against entertainment shows in prime time, Don Hewitt, the show’s creator, knew that he had to produce something that wasn’t a traditional news program. It would not be built around the important news of the day (or the week), but would be a weekly series that emphasized storytelling, introduced journalists as protagonists, and created drama around their exposing bad guys or tangling with the powerful and famous. “There are TV shows about doctors, cowboys, cops,” Hewitt once said. “This is a show about four journalists. But instead of actors playing these four guys, they are themselves.” With this formula, “60 Minutes” became the first successful prime-time newsmagazine. As such, it was also the first news program to generate big profits for a network. Given this combination, it became a harbinger of things to come.

Roone Arledge’s arrival as President of ABC News in 1977 created even more momentum for industry-wide change. Arledge, an ingenious and innovative executive who had made his mark in sports, had become a power at ABC because of the profits he’d made as the head of ABC Sports. He saw no reason why news couldn’t make a profit, too. So Arledge set out to get more programs onto the air, creating “20/20,” “Nightline” and “This Week with David Brinkley.” He also used his talents as a producer and promoter to package news, including serious news, to appeal to a mass audience. By the late 1980’s, ABC News—still under Arledge’s leadership—had become the industry leader in profits and prestige. Soon the other networks were trying to catch up by adopting a similar game plan, producing more news and doing so in ways that appealed to non-news audiences.

Most important in this chain of transformation, all three networks changed hands in the 1980’s. General Electric bought NBC. Capital Cities Communications bought ABC. And Laurence Tisch, a hotel and theater magnate, assumed control at CBS. These new owners stepped up the pressure on the news divisions to become more efficient businesses, particularly as the increased presence of cable networks eroded the networks’ overall profit margins.

“When I came here, we were losing money in news and that was thought of as an acceptable situation,” recalls Bob Wright, who has been NBC’s Chief Executive Officer since GE bought the network in 1986. The losses at NBC News were substantial, as much as $100 million a year. “That was unique, to my experience,” Wright says. “I had been in businesses where we didn’t make any money, but that was never the goal.” Wright’s first instinct was to ask his news division to break even. Soon, however, he and the other network owners decided they could do better. They focused sustained attention for the first time in the news divisions on controlling spending. They hired management consultants to analyze costs and look for cuts. Andrew Heyward, now President of CBS News, says: “There had been a long period during which the news budgets were very generous, and there was not a lot of attention paid. There’s no question that in the latter half of the 1980’s, certainly at this place, there was a new emphasis on the cost of producing the news.”

The formula for making network news into a profitable business was thus established:

- Make the product more entertaining. As Hewitt proved with “60 Minutes,” when you tell stories in ways that engage the audience, often by touching their emotions, news programming can generate high ratings and revenues.

- Produce more programming. As Arledge established, in business terms a network news operation can be seen as a factory with a lot of fixed costs: bureaus, studios, equipment, correspondents, producers, editors, executives and network overhead. The more programs that the factory can churn out, the more revenues can be generated to recoup these set costs. Once those fixed costs have been paid for, the marginal costs of producing more hours become relatively low.

- Control spending. Wright, Tisch and Capital Cities did this, and today’s owners are continuing to do it. The networks have, among other things, closed foreign and domestic bureaus, laid off staff, eliminated some money-losing documentary units, and curbed convention and election coverage.

The Prime-Time Strategy

If, to become profitable, network news divisions had to become more entertainment-oriented, produce more hours of programming, and control their costs, there was only one place to turn: prime time. Prime-time newsmagazines can tell compelling stories, attract bigger audiences, fill more hours, and operate more efficiently than unpredictable hard-news programming.

This explains a profound shift in emphasis in the news divisions at the Big Three. Each has moved away from hard-news reporting and the evening newscasts, which were once their signature programs, and towards prime time. This is not to suggest that event-driven, daily news programs are no longer valuable to the networks. They are, especially those shows that make money, such NBC’s “Today” and ABC’s “Nightline.” But prime-time programs command center stage. It’s no accident that two of the three network news presidents—NBC’s Andrew Lack and CBS’s Andrew Heyward—made their reputations as producers for prime time. “The magazines have clearly become the tail that wags the dog,” says Tom Bettag, the Executive Producer of ABC’s “Nightline.” “They generate far more profit than anything else we do.”

At the networks, hard news has become an unappealing business. Ratings and revenues for most hard-news programs are declining, and reporting breaking news is expensive. Ratings for hard news have slid, in part, because of the explosion in alternative news sources. Consumers can pick up stories from all-news cable, Internet news sites (including those operated by the networks), local stations (which broadcast up to six hours of news a day in major markets), business cable news outlets, the Weather Channel, sports news channels, all-news radio and National Public Radio. As one Wall Street analyst, James M. Marsh, Jr., of Prudential Securities, puts it: “There is currently an overabundance of news programming, with supply easily outstripping demand.”

In response, the newscasts anchored by ABC’s Peter Jennings, NBC’s Tom Brokaw, and CBS’s Dan Rather are reporting fewer “headline” stories, preferring to highlight in-depth stories, live interviews and news-you-can-use. Even so, their combined audience share has declined from a peak of 75 percent in 1980 to 47 percent in 1998. (These percentages represent the share of audience that is watching TV during the dinner hour.) Of all TV homes, less than 24 percent watch an evening newscast on any given night, down from 37 percent in 1980. The trends seem irreversible.

These declining ratings exert downward pressure on advertising revenues. However, at the networks, advertising revenue from news has not declined substantially, at least not yet. (Precise numbers are hard to come by, but media buyers say that all three newscasts collect between $40,000 and $50,000 per 30-second spot, roughly the same as in recent years.) Because ABC, CBS and NBC still reach mass audiences, unlike the cable news networks, sponsors are willing to pay a premium to reach their viewers. Newer advertisers, particularly pharmaceutical companies, also help keep the demand strong. Demographic research tells advertisers that more than half of the viewers of the evening newscasts are 55 and older. This is great if you’re a sponsor who wants to sell arthritis medication, but not so good if you’re a network news executive with eyes focused on the future.

Even though the rates advertisers pay have held up well, one sign of the pressures network executives are working under is the fact that more time is being devoted to selling products and less to broadcasting news. ABC now sells seven minutes of national spots during each nightly newscast, up from six in 1993. Take away the time devoted to local commercials and promotions, and there are only 20 minutes and 45 seconds left for news. On CBS, there are 21 minutes. And at NBC, the viewers get 15 seconds more, according to the American Association of Advertising Agencies.

Cutting Costs

With their newscasts’ ratings slipping and revenues flat, news divisions, looking to increase profits, feel they have had little choice but to control the costs of gathering news. Layoffs have become periodic occurrences during the past decade. During the fall of 1998, all the networks reduced staff. CBS was hardest hit, eliminating about 120 positions from its 1,600-person news staff; most were technical, office and managerial people, not correspondents and producers. ABC thinned its executive ranks, and some high-paid correspondents and producers were also let go. NBC imposed a hiring freeze in news, as well as in the rest of the company, after the network lost its biggest moneymaker, “Seinfeld,” and negotiated a contract with its leading prime-time drama, “ER,” that required huge per-episode fees.

“If I told you that there was a date certain when we were going to stop cutting costs, you shouldn’t believe me,” says David Westin, the President of ABC News. “It’s an ongoing process.” Ongoing, indeed. Several experienced, hard-news correspondents, people such as medical specialist George Strait, legal correspondent Tim O’Brien, and former Hong Kong Bureau Chief Jim Laurie have left or are about to leave ABC News.

One problem the networks face as they cut back is that breaking news is unpredictable. Like firehouses, news bureaus need to be staffed for emergencies, but often the correspondents and producers are idle. Stationing people in distant locales is inherently inefficient. Even when big stories erupt, some inefficiency is inevitable. As CBS’s Heyward explains: “If you’re going to gather news around the world, that’s not inherently profitable the way creating a newsmagazine is. When you create a newsmagazine, most everything you produce gets on the screen—you can choose what to cover, and that’s very efficient. But if you’re running a London bureau, even if you run it lean and mean, when there’s a threat of war in Iraq, you’re going there. You put somebody on the cruiser or on the battleship without knowing how many pieces he or she is going to generate.”

Each network defines what it calls a “bureau” differently, and staffers are shifted with some regularity. This makes it hard to obtain comparable data on how many bureaus have been closed and how many remain. In October 1998, ABC News had five foreign bureaus staffed with correspondents. CBS News had four. And NBC News had seven, according to The New York Times. By comparison, CNN had 23. What is clear is that the Big Three have retrenched. None still has a full-time correspondent stationed in southeast Asia, Central or South America, or sub-Saharan Africa, except for staffers shared by CBS’s Spanish-language arm, CBS Telenoticias. Domestic bureaus have also been closed. Rather than maintain full-time staff in far-flung outposts, the networks have found ways to obtain what they call “generic” coverage—images that are widely available—from outside sources. They use footage from foreign networks, from their own affiliates, even from independent suppliers such as NewsTV, a company that provides coverage to the networks from its headquarters in Lawrence, Kansas.

"It is not death or torture or imprisonment that threatens us as American journalists, it is the trivialization of our industry….”

—Ted Koppel

“We’re building an empire on being the Kelly Girls of network news,” says Russ Ptacek, a former local TV reporter who is President of NewsTV. Even programs that don’t rely totally on hard news, such as “20/20” and “Today,” use his 26-person operation, he says, because “the only time the networks are paying for our services is when we’re on location, working for them.”

Last year, ABC, NBC and CBS each had discussions with CNN about sharing staff and bureaus outside of the United States. While a full-fledged merger between a broadcast network and CNN, now part of Time Warner, appears unlikely, increased cooperation of some kind seems inevitable. The technique of “pooling,” in which news operations share footage from a single camera as they do in Congress and at the White House, has already begun to spread overseas. “Internationally, you will probably see some consolidation of resources,” says Pat Fili-Krushel, the President of ABC, who oversees ABC News.

The networks argue that they don’t need as many bureaus and reporters now because their role has changed. Rather than trying to be first on the air with a headline or a picture, the mission at ABC, CBS and NBC is defined as providing so-called value-added programming—in-depth analysis and original reporting that 24-hour cable services and local TV can’t duplicate. This makes sense, but it’s difficult to provide thoughtful reporting of stories around the nation and the world without reporters on the ground who are given the resources to develop expertise. Paul Friedman, Executive Producer of ABC’s “World News Tonight,” says, “Journalism is about going out and looking at things, and you can’t do that by buying video from APTV…. You wind up doing a lot more of what we did before the news budgets expanded and that was parachute in. If you have good people who have a lot of experience, you can generally parachute in and do a good job. But it is not the same as having somebody on the ground who calls you and says, you know, you really ought to come and look at this developing story.” The same goes for coverage in Washington, where specialized beats have been gradually eliminated or several assignments have been combined.

The war in Yugoslavia in the spring of 1999 exemplifies some of the problems that accompany these new approaches to network news coverage. No network had been covering the emerging crisis in Kosovo on an ongoing basis. Few reporters knew Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, knew much about the tensions fueling the crisis, or had established sources in the region. Even the best correspondents covering the NATO bombing and the mass eviction of Albanians were new to this story. When the Pentagon and the Serbs both clamped down on information, many in the press were largely unprepared to cover aspects of this story and, as a consequence, many critics felt the public was ill served.

The Emergence of Newsmagazines

Compared with hard news—expensive to cover and limited in the return it can deliver—the economics of primetime newsmagazines are very attractive. They don’t require bureaus with people stationed around the world. Typically, they rely on their own staffs of producers and correspondents to cover stories that they decide when, where and how to do. Controlling costs becomes easier. Executives in charge of newsmagazines can opt not to cover a complicated high-cost story, or they can decide to keep staff closer to home rather than pay for expensive travel. Unlike the daily news programs, newsmagazines do joint ventures and piggyback onto coverage generated by others. For example, NBC’s “Dateline” does projects with People and In Style magazines, Court TV and the Discovery Channel, among others, all of which save money.

As a result, newsmagazines are also a low-cost alternative to dramas or sitcoms in prime time. To produce an original hour of a newsmagazine typically costs between $500,000 to $700,000. An hour of entertainment costs the network at least $1.2 million. This cost advantage for news isn’t quite as great as it seems; sitcoms and dramas can be repeated while most news programming is original. Still, newsmagazines have started to do more repeats and “updates” of stories that have previously aired. So they don’t have to produce original episodes year round, and this drives costs even lower.

Producing more news programming brings other long-term advantages to networks. Unlike most sitcoms or dramas, the network owns its news programs. While the costs of on-air talent rise over time, it’s easier for CBS to control the overall costs of “60 Minutes,” for example, than it is to hold down costs of a popular entertainment show that is owned by a studio. (The most dramatic recent example is “ER.” Warner Bros. now charges NBC $13 million an hour. Top-rated, half-hour sitcoms cost $1 million or more per half-hour.) Owning news programs also means that they have residual value to the networks. Libraries of news footage can be recycled into programs such as Arts & Entertainment’s “Biography” series or MSNBC’s “Time & Again.” These shows pay the broadcast networks for old footage.

Newsmagazines, as a genre, perform nearly as well as entertainment on a year-round basis. In the summer, these programs perform better than dramas or sitcoms, since they still feature new programs while entertainment shows are repeats. NBC President and CEO Bob Wright observes that it’s become a “tossup” as to whether another hour of “Dateline” will do better or worse than whatever new drama or sitcom his Hollywood executives want him to put on the air. “It didn’t used to be that way,” Wright says. “The feeling was that a decent entertainment show is going to do twice the audience of a news show. In the hands of these producers, that isn’t true.”

During the 1998-99 TV season, the average price for a 30-second commercial on “Dateline” ranged from $90,000 to $130,000, depending on the night of the week it aired. Advertising rates for “20/20” averaged $135,000 to $160,000. On CBS’s “48 Hours,” the cost was $80,000. And spots on “60 Minutes” (Sunday) average an impressive $240,000. All of these rates are much higher than those generated by an evening newscast, though, except for the “60 Minutes” rates, they are still below the network averages for primetime entertainment. Still, given their lower costs, news shows right now are a better business for the networks than entertainment programming.

Not surprisingly, the number of prime-time magazines has grown over the years. As recently as the mid-1980’s, there were only two—“60 Minutes” and “20/20”—each airing once a week. The networks were reluctant to turn over valuable prime-time real estate to their news divisions. In the early 1980’s, CBS canceled prime-time programs hosted by Charles Kuralt and Bill Moyers that, if judged by today’s standards, would be ratings hits. However, by 1990, CBS’s “48 Hours” and ABC’s “Prime Time Live” had been added to the mix. “Dateline” provided NBC with its first successful magazine show in 1992. The network then pioneered the idea of broadcasting multiple editions of the same magazine, a cost-effective approach that allows the network to focus its resources and promotion on a single prime-time news brand. Last year, ABC copied that idea by folding “Prime Time Live” into “20/20.” In January, CBS introduced a second edition of “60 Minutes,” launched at the behest of CBS corporate executives Mel Karmazin and Leslie Moonves over the initial resistance of Hewitt and news executives. That decision, by itself, was evidence of how important prime-time news now is to the networks.

There is recent evidence that a saturation point has been reached. Ratings were down substantially for “20/20” and “Dateline” during the 1998-99 TV season. It’s too soon to say whether the declines, ranging from seven percent to 16 percent depending on the night of the week, reflect overall network erosion or viewer dissatisfaction with the magazine genre. David Westin, President of ABC News, says: “As there is failure on the entertainment schedule, there’s a tendency to say, ‘let’s put another newsmagazine on.’ And we have to be concerned about the quality of those newsmagazines. There has to be a point where the quality of the stories we are putting on is not what our viewers have come to expect. We have to be very concerned about that.”

“Television is an entertainment medium, and it’s always been shaky and unsure about how to present news….”

—Richard Reeves

Some critics of the television magazine shows say the networks have already passed that point. In a speech at the Media Studies Center last year, Don Hewitt, of “60 Minutes,” said: “The sad fact of life today is that the economics of television have, in no small measure, driven the networks out of the entertainment business, which they used to be very serious about and did very well, and into the news business, which they’re not very serious about and don’t do very well.” Hewitt made clear in his speech that he wasn’t talking about the evening newscasts or his beloved “60 Minutes.” He was referring to “all those so-called newsmagazines that followed in the wake of ‘60 Minutes,’ newsmagazines the networks use as filler because they’ve got no alternative.” Filler or not, the magazine programs now reach more viewers than any other news programming on television—or, for that matter, any journalism of any kind in America. It’s worth taking a closer look at what they have to say.

Prime-Time “News”

Whatever one thinks of the network prime-time magazines, even a casual viewer can see that they are not governed by news values in the traditional sense. Executive producers of these magazines don’t see themselves as under any obligation to cover the most important stories of the moment. Nor do they act like the kind of journalist whose job it is to provide citizens with information they need to participate in a democracy.

A randomly selected night—Wednesday, June 2, 1999—of magazine viewing provides an anecdotal sense of what these programs are offering viewers. NBC’s “Dateline” presented “stories of survivors,” an entire program devoted to sagas of natural and man-made disasters. There was a story about an Arizona desert thunderstorm that caused a severe wreck of an Amtrak train. Another was about a sinking oil tanker in the Indian Ocean. A fire aboard a chartered fishing boat in Hawaii that left five people briefly stranded was also featured, as was an update on an American Airlines plane crash in Little Rock that had happened the night before.

These stories were produced and broadcast for their entertainment value, not to illuminate any significant broader issue. As the announcer at the top of the hour said: “In the blink of an eye, hope turns to heartbreak, triumph to terror. And a single second can mean life or death. These are the incredible stories…” Most of the pieces relied upon home video supplied by eyewitnesses, and in many ways the NBC News broadcast was indistinguishable from the reality special, “World’s Most Amazing Videos,” that followed it.

CBS’s “60 Minutes II” was meatier. A story by Dan Rather examined lax swimming pool standards which, according to lawyers for the victims, contributed to severe, heartbreaking head and spinal injuries to young divers. Charlie Rose profiled New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. And Lesley Stahl updated a superb story on institutional racism in the Marine Corps, reporting on substantial improvements in the racial climate since the original “60 Minutes” story ran.

ABC’s “20/20” presented a report from Chris Wallace on a man who made hundreds of harassing phone calls to his neighbors in Virginia Beach, Virginia, after eavesdropping on their cordless phone calls. The broadcast then repeated, with no new information, a story by Cynthia McFadden on Russian women being sold into slavery to work in brothels. Like NBC, “20/20” also did an update on the Little Rock plane crash, and John Stossel complained about a poor rural county in Mississippi that was forced to spend well over $250,000 to defend two indigent men convicted of murder and sentenced to die.

What was notable about all three programs was not what they put into their broadcasts, but what they left out. There was no news from Washington, none of the war in Kosovo (which, in fairness, “Dateline” covered extensively during the spring), nothing about the upcoming election in South Africa, the economy, education or any societal institution, other than the military. What’s more, while some of the primetime stories were well told and touched on important topics, others had a tabloid feel. On “20/20,” in particular, stories were given movie-like names (“Someone May Be Listening,” “Girls for Sale”) and sold with overheated language (“a story right out of a horror movie…a neighborhood terrified by a mysterious, menacing killer…sex slaves…thousands of women sold to brothels”). The sex story, of course, featured footage of scantily clad women.

Does this snapshot offer enough evidence for a fair assessment? Other examinations of the newsmagazines suggest that it does.

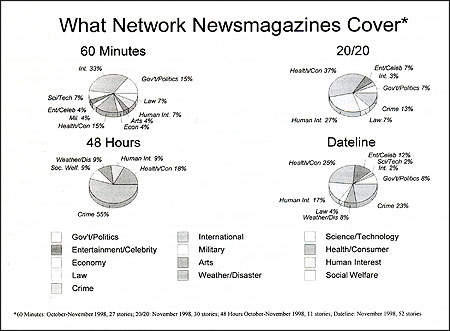

The Project for Excellence in Journalism conducted a content study of “60 Minutes,” “20/20,” “Dateline” and “48 Hours” during a two-month period in the fall of 1997. Its findings confirm what similar studies have found. These newsmagazines provide extensive coverage of crime and justice and human-interest stories, news-you-can-use about health and consumer problems, and scandals and celebrities. I also looked at videotapes or transcripts of these newsmagazines from October and November 1998 and found story selection to be much the same.

Each program, of course, has its own niches. [Please see chart above.] On “20/20,” for example, more health stories appear than on its rivals. In one month, “20/20” did two segments about diets, as well as other stories warning viewers that bickering is bad for their health, that paper money is contaminated with germs that can make them sick, and that uncontrollable sweating can be a serious medical problem. “Dateline” is heavier on crime. It headlined segments about a boy who killed his best friend’s mother, another boy shot outside a hospital emergency room, a notorious fugitive from justice now living in Europe, and a political candidate in the midst of a campaign. “Dateline” also does more hard news than its rivals, providing extensive coverage recently of the Littleton school shootings as well as reporting from Yugoslavia.

Magazine stories, in general, have a common thread. They are driven more by emotion than by ideas. This helps explain why the magazine stories pay far less attention to the traditional news topics of government, politics, education, economics, business, the environment and foreign affairs. Again, however, the shows can’t all be lumped together. “60 Minutes,” for example, is more willing than the others to venture overseas. During November, “60 Minutes” did stories about slave labor performed by Jews during the Holocaust, about the defection of an aide to Saddam Hussein’s son, about British Prime Minister Tony Blair, about the aftermath of genocide in Rwanda, and about the civil war in Kosovo. By contrast, “20/20” and “Dateline” rarely do foreign news unless it is about Americans abroad. In all of 1998, neither “Dateline” nor “20/20” devoted a single story, out of more than 1,500 that were broadcast, to the civil war in Kosovo, one of the most important foreign news stories of the year, as Americans would later learn.

None of this is to say that these magazines don’t provide valuable public service programming or investigative journalism; all of them do, at least occasionally. And they fill the evening television hours that were once occupied by sitcoms or dramas. (The elimination of the networks’ documentary units is another matter, but that wasn’t caused by the increase in these magazine shows.) Still, it is clear that the task of programming a prime-time magazine bears little or no resemblance to the job of assembling a nightly evening newscast, a morning news show, or a good newspaper. Regular viewers of the “CBS Evening News,” NBC’s “Today” or ABC’s “Nightline” will, over the course of time, become reasonably well-informed about important domestic and international issues; the same can’t be said for viewers of magazines. As Victor Neufeld, Executive Producer of “20/20,” has said: “Our obligation is not to deliver the news. Our obligation is to do good programming.” Put another way, these programs are market-driven, shaped more by entertainment values than by the traditional ideas about news. Yet without the success of the prime-time magazines, the networks would find it difficult, if not impossible, to present traditional news programming during other parts of the day. Because the magazines are where the news divisions now make their money, these profits subsidize traditional news coverage.

Economics of Network News

Of the Big Three, NBC News is the best-positioned from a business standpoint, for now and in the immediate future. NBC News earned more than $200 million in 1998, according to network executives, and its profits have been growing steadily during the decade. NBC CEO Bob Wright expects its profits to continue to grow. News, Wright said, needs to contribute to the bottom line, just as other divisions do, and NBC News President Andrew Lack says he will be able to deliver. “This news organization has become an attractive business, long-term,” says Lack. “We see huge opportunities to grow on the broadcast platform, to grow in cable, to grow in global markets, and, of course, on the Internet.”

NBC’s financial success is partly ratings-driven. The “NBC Nightly News” is the top-rated evening newscast, albeit by a slim margin, and the “Today” show dominates its competitors in the morning. More significant for the long term, however, is the model for television news that Wright and Lack have developed. With the expansion of “Dateline” and the 1996 launch of MSNBC, NBC’s cable and Internet joint venture with Microsoft, the news division’s profits have increased. “What’s really allowed us to become profitable is that we have significantly expanded the number of hours of programming,” Wright says. Eventually, Lack says, “MSNBC will be seen as the most important thing that has happened to NBC News, bar none.”

Here is why this model works so well. ABC and CBS generate nearly all of their income from broadcasting. NBC takes in additional revenues from cable (MSNBC, CNBC), NBC’s Internet sites, and NBC News channels distributed outside of the United States. Fast-growing CNBC alone will bring in revenues of nearly $400 million in 1999, up 30 percent over last year, and earn pretax profits of $200 million, up 42 percent. Therefore NBC is better able to shoulder the overall costs involved with newsgathering, since its bureaus and correspondents provide newsgathering not just for the “Nightly News” and “Today,” but for its 24-hour cable networks and Internet sites as well.

For example, when Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan testifies before Congress, NBC can send a correspondent and crew to gather footage for all its outlets—broadcast, cable and Internet. This is a major competitive advantage. It means that NBC can afford to pay higher salaries to anchors such as Brian Williams and Jane Pauley, as well as for producers and correspondents. Better yet, MSNBC and CNBC aren’t as ratings-dependent as the network broadcasters are because they collect fees from cable subscribers in addition to advertising dollars. Cable fee revenues are more predictable than advertising, and they are growing. By programming more than 6,000 hours of news a year across its broadcast and cable platforms, the average cost per hour of news at NBC has fallen from about $250,000 to $50,000 during the past five years. The NBC news factory is running efficiently and its future seems secure, as it remains the only news provider with a strong presence on broadcast TV with its mass audiences, on cable TV where news is available around the clock, and on the Internet, where news is interactive.

The same can’t be said of the other broadcasters. ABC and CBS must maintain their newsgathering forces to stay competitive, but they are only able to recoup their costs from the few hours of network news they broadcast each day. Currently, ABC News remains profitable—it earned about $55 million last year—but that’s down from a peak of more than $110 million a few years ago. That kind of slippage is serious enough that its owner, the Walt Disney Co., whose earnings declined sharply in the last quarter of 1998 and the first quarter of 1999 and whose recent stock price has lagged behind other media companies, cited the decline in ABC News ratings as one factor. Disney expects all its divisions to increase their profits each year, and Pat Fili-Krushel, the ABC Network President, says improving the news division’s economics is one of her top priorities.

What’s not clear is how ABC News will manage a turnaround. Profits have fallen because of the steep ratings decline at “Good Morning America” and because “World News Tonight,” once the most-watched evening newscast, has fallen behind NBC. In response, ABC News President David Westin brought veteran executive producer Paul Friedman back to “World News Tonight” and temporarily installed stars Diane Sawyer and Charles Gibson as the anchors of GMA. The ratings perked up momentarily in the morning, but permanent new hosts still have to be found. “I can spend all my time trying to close a bureau or consolidate a crew, but it is really small potatoes compared with improving ‘Good Morning America,’” Westin says. “You can cover an awful lot of problems very quickly with a successful program.”

Meanwhile, Westin has begun to outline an intriguing strategy for ABC News. He says he would like to make “Nightline” the network’s signature program and make ABC the news network of choice for intelligent viewers. As it happens, “Nightline” delivers both healthy profits, thanks to its upscale audience, and journalistic excellence. The five-nights-per-week broadcast is put together by a relatively small staff of about 40 people, a well-regarded Executive Producer, Tom Bettag, and, of course, the respected Anchor Ted Koppel. It is a model for network news in a slimmed-down era, delivering not familiar headlines or coverage but fresh analysis, context and explanation.

Westin argues that the cable news networks have won the battle to be first with news when viewers want it. No longer, he says, can a broadcast network make its reputation by breaking in with the big story, as ABC did in the Arledge era. Instead, Westin argues, “We have to pursue a different strategy, bringing you distinctive, high-quality, in-depth coverage, from people who know what they’re talking about and have something to say.”

“…the fact of the matter is the audience did not show any true interest in the Bosnia story.… they’re giving us a message that this story is not all that important to them….”

—David Corvo

This strategy happens to be compatible with cutting costs, another priority at ABC. Westin compared the network news divisions to the U.S. steel industry of the 1950’s, saying they are locked into outdated processes and bloated labor costs. They need restructuring, he said: “We have to prune and grow at the same time. The test of our success will be, are we pruning in the right places and growing in the right places?”

Westin’s plan is to determine what ABC News does best and spend there—on high-quality anchors, correspondents and producers, in particular—and then cut back on generic coverage. “People don’t pick a newscast anymore based on who has the picture of the plane crash,” he says. They pick it, he says, based on who has the smartest and most knowledgeable people. Westin says he will try to save money by forming newsgathering partnerships and spending less money for correspondents and producers who do not add value to the product. These employees will have to take salary cuts or be let go. “You have to be ruthless, and it’s not fun,” Westin says. Senior executives at the ABC network insist ABC News has room for cost cutting because it remains the highest-cost provider among the networks, spending far more on news than, say, CBS.

The problem is that management of a news organization is more art than science, and the task before Westin leaves little margin for error. How, for instance, do you increase quality and shrink resources? Less can be more but it usually isn’t. To add to the difficulty, Westin, a lawyer by trade, has limited experience as a TV producer, and many inside the network harbor real doubts about whether he can execute his strategy. Which correspondents and producers will he decide, for example, add value to the product, and which do not? The tendency in network news today is to answer that question by paying ever more for celebrity anchors while shrinking the ranks of correspondents and producers who actually report the news. This appears to be happening at ABC as well. While jettisoning O’Brien at the Supreme Court and legal affairs and Strait, who covered medicine, the network renegotiated a new contract with celebrity pundit George Stephanopoulos who, according to Westin, was now “recasting” himself from liberal commentator to TV journalist, reporting and anchoring. While Stephanopoulos is popular for the moment, will his presence enhance viewers’ trust in ABC News over the long run? Westin and others may be walking a knife edge here.

Once-proud CBS, the network where broadcast news was invented, is now struggling to make even a modest profit. It earned only about $15 million in 1998, according to industry insiders. The network won’t confirm that figure. “CBS Evening News” remains the number three evening newscast, lagging by a substantial margin during the first half of 1999. The same goes for CBS’s morning program, although the addition of star Anchor Bryant Gumbel and a new studio on Fifth Avenue should deliver a ratings boost. Another problem is that the CBS audience tends to have a greater percentage of older viewers than the other two networks, and these older viewers are worth less to advertisers. And CBS schedules fewer hours of news each week than either NBC or ABC.

Despite all that, CBS News’ earnings are growing. Cost reductions have helped, as did the January 1999 launch of “60 Minutes II,” which gives the network another hour of revenue-generating prime-time programming. The program is off to a promising start, critically and commercially. CBS also struck a deal that bodes well for the future: It will become the exclusive broadcast news provider to America Online, which should give it not only a new source of revenues but access to millions of Internet users. CBS’s Heyward contends his news division’s worst problems are behind it. “After some challenging years in the mid-1990’s, we are rapidly moving in the right direction,” he says. “We’re having substantial financial success.”

Heyward’s strategy for CBS is similar to Westin’s at ABC. He intends to cut costs, but aims to provide unique programming. “We’re looking to be more efficient in gathering what I would call the raw material or generic news, so we can devote our resources primarily to added value,” Heyward says. “You don’t want to have your camera in the Knesset with five others. If Reuters or someone else can get the Knesset shot, then your crew can go out to the West Bank and get the exclusive interview that will make your piece special.”

While rivals at ABC question whether CBS News still has the resources to deliver a quality product, CBS has one big advantage in the competition to be the best: “60 Minutes.” Unlike ABC, which is identified with the softer, more tabloid “20/20” (whose trademark is news-you-can-use) or NBC (whose signature program is “Dateline”), CBS has “60 Minutes” as its prime-time standard bearer which, in the public’s mind, stands for high impact, quality journalism. Although it’s been on the air for just a few months, “60 Minutes II” also seems to be aiming higher than the magazines at the other networks.

Still, without dramatic cost cutting or cost sharing or an equally dramatic expansion of programming hours—such as an hour-long prime-time daily news program—the economics for ABC and CBS are going to be difficult in the years ahead. As “CBS Evening News” Anchor Dan Rather said recently: “It’s entirely possible that one of the Big Three television organizations will cease to exist in five or seven years.”

The Quality Solution

On one theme, the three network news presidents agree. No matter how the television landscape changes, they insist, viewers will continue to be attracted to high-quality news programming. This may sound like wishful thinking, but it is borne out by history. Programs like CBS’s “60 Minutes” and ABC’s “Nightline,” which are admired for their consistent quality, are also among the most profitable and long-lasting franchises in television. The same is true for NBC’s “Today,” which earns about $50 million a year in profits for the network. Its first half-hour is filled with hard news, including overseas and Washington coverage, that is well-produced and timely.

“Good journalism is good business,” says NBC’s Lack. “‘60 Minutes,’ ‘Nightline’ and the ‘Today’ show are these unique programs that go back for…years, that are just embedded in the national consciousness as very reliable, quality programs. Each of us is fortunate to have one of those franchises. They’re pillars.” In fact, unlike dramas and sitcoms, which run out of steam and leave the air, established news programs seem able to go on for decades. CBS’s Heyward says news programs offer “a wonderful combination of the familiar and the new,” familiar faces and formats, renewed daily or weekly with new headlines and fresh stories. Says Westin: “They go on forever, you don’t have to reinvent them, and they draw an audience, week after week, month after month.” In an industry in which four out of five new entertainment programs fail, a successful news program becomes a jewel worth protecting.

The trouble is that creating a franchise like “Today” or “60 Minutes” or “Nightline” is no easy feat, especially now. Network presidents say they want quality, but will they be able to deliver? Consider some obstacles they face:

- The pool of talent is thin. Anchors such as Mike Wallace and Ted Koppel don’t come along every day. Nor do executive producers like Don Hewitt and Tom Bettag. It’s interesting to note that today’s network “stars”—Wallace, Koppel, Rather, Jennings and Brokaw, or Hewitt and Bettag behind the scenes—came of age during the era when TV news was hard-news oriented and shaped by the old values of public service. Each served long apprenticeships covering breaking news: Jennings and Koppel spent years overseas, Rather and Brokaw covered Washington when government and politics were more important to the networks, and Hewitt and Bettag polished their craft producing CBS’s flagship evening newscast. Such training is now largely a thing of the past. Many young producers and correspondents are rushed into prime time where the values are market-driven. It is telling that when ABC decided it had to try and save “Good Morning America” it turned to familiar faces, Charles Gibson and Diane Sawyer, who were trained in the old school.

- New programs need time to develop. From network executives, new programs require patience, a faith in the eventual audience and, often, a willingness to experiment. “60 Minutes” took nearly a decade to ripen into a hit show; the show was tolerated for years because CBS was so profitable that it didn’t need to maximize revenues during every hour of the broadcast day. “Nightline” arose out of the Iranian hostage crisis, when ABC was willing to commit to late night coverage in order to grab attention and enhance its news image; such a scenario would be highly unlikely today, with networks having all but ceded extensive special-events coverage to the all-news cable networks.

- Quality programs depend on a special bond between the networks and their viewers. In essence, viewers need to believe that the networks are the place to turn for intelligent, thoughtful television journalism. This is the notion behind “branding,” which is so valued in business today and has been an important part of the tradition of network news. For all their flaws, the network news divisions for years differentiated themselves from local TV news or syndicated programs because they promised and delivered a product that was perceived as having integrity and quality. The success of magazines such as “20/20” and “Dateline” stems partly from the power of their network brands; viewers who trust NBC News or ABC News, after years of watching Brokaw, Jennings and Koppel, believe that they can expect the same quality in prime time. The danger, of course, is that the primetime feature and infotainment programs will fail to meet those expectations, and the value of the network brands could erode.

The question now is, given all the changes and pressures occurring in the news broadcast industry, whether a culture of journalism still exists at the networks to surmount these obstacles and achieve real “brand” quality. Can a new generation of stars with journalistic experience, authority and skill emerge from the plethora of feature prime-time magazine programming to match the quality of the now-aging cohort of network stars? Do the networks still have the patience to support a high quality news program such as “Nightline” or “60 Minutes” through years—not to mention a decade—of losing money until it builds a loyal audience base? And, more importantly, will any of the networks invest what it takes to fulfill their commitment to comprehensively informing the public about the major issues and events of our time once they have established new bonds with viewers?

The networks probably have a greater stake now in developing the highest quality talent, in demonstrating patience, and in protecting their brands if they want to maintain a loyal cadre of viewers from among the splintering audience. With the proliferation of channel choices, no news division can afford to settle for second-rate programming. The best programs and brands will survive and even thrive in this cluttered environment. It’s a good bet that viewers will continue to seek out “60 Minutes,” but it’s not clear whether they’ll hunt for “Dateline” or “20/20,” which are more dependent on hype, gimmicks and stories that pander to their audiences. If news becomes available on demand and for a fee (as it might), some people will probably pay to watch “Nightline,” as long as it retains its excellence.

The economic forces now buffeting the business of network news are unlikely to abate. Viewers and advertisers will continue to have more, not fewer, choices in where to turn for their news and marketing. Profit pressures at network news divisions will intensify, not diminish. In this unforgiving environment, the question is whether the core requirements necessary to provide solid journalism—time to pursue stories and develop sources, a recognition that not all coverage is going to produce immediate profit, an ability to focus on important topics that won’t bring high ratings but can build viewer trust—can be sustained. If history holds true that audiences in the long run gravitate to quality, network aspirations will not be enough. The networks will need to take the risk and time to invest in quality.

Marc Gunther is a senior writer at Fortune magazine. He has covered network television since 1983 and is the author of “The House That Roone Built: The Inside Story of ABC News,” published in 1994.