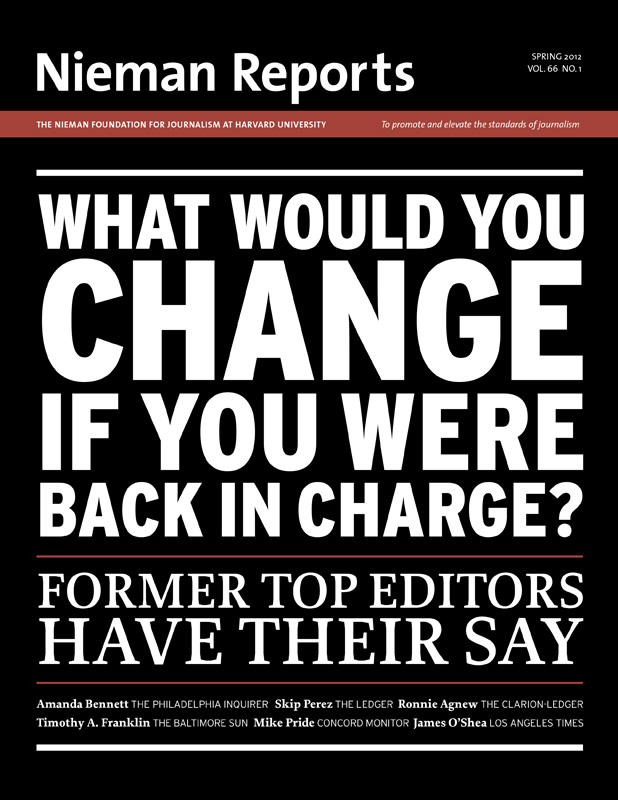

Skip Perez, above in 1980 at his former paper in Florida, would like to see a “training renaissance.”

When I retired in January 2011 as executive editor of The Ledger, a 55,000-circulation daily in Lakeland, Florida, I had had my fill of reorganizing and restructuring, redefining and realigning. These terms were euphemisms for “We must slash payroll because advertisers aren’t spending like they used to. And our profit is shrinking. So our stockholders aren’t happy. And Wall Street is dissing us. So you gotta do more with a helluva lot less. Congratulations, you now have four titles!”

I was asked to write about how I would do things differently if I were leading a newsroom in today’s hectic media landscape. But I can’t do justice to that assignment for two reasons: 1.) I have no clue what I’d do differently or better because I operated largely on instinct based on what I observed, feedback I received, and what I thought our readers deserved to know, and 2.) I now sense a much more fundamental problem that deserves thoughtful, immediate attention—a creeping despair that requires a sustained and systematic assault because it poses a serious threat to journalism.

Newsrooms have never been wellsprings of optimism, even in the best of times. But this is different. Unrelenting awful economic news about most media companies has contributed to an atmosphere of fear and insecurity among many if not most journalists. Those anxieties are well founded. Nearly 14,000 newsroom jobs have been eliminated since 2007, according to the American Society of News Editors (ASNE), and a visit to Erica Smith’s excellent website newspaperlayoffs.com shows the steady stream of layoffs across the industry.

Eroding faith in a noble calling is a plague on the craft, with far-reaching implications for the future of the profession and, more important, democracy. But my sense is that almost everyone is overlooking the “people piece,” meaning the newsroom staffers who should care deeply about the quality of their work and feel good about it every day. Certainly one may argue they should be grateful to have a job, and most probably are. But simple gratitude falls far short of the excitement and zeal that dominated newsrooms 42 years ago when I landed my first reporting job. How might newsrooms recapture that essential spirit, short of hiring a managing editor for psychotherapy?

As most editors know, a newsroom that aggressively pursues important, hard-edged stories on a regular basis is less susceptible to the culture of complaint. The work is noticed and celebrated. It is a wonderful antidote to pessimism.

To nurture this atmosphere, particularly at smaller newspapers with which I am most familiar, a commitment to staff training is essential. Training budgets are among the first to be eliminated when money gets tight. But the right kind of training will boost morale and reward the news organization with dedicated staffers itching to tackle groundbreaking assignments. And those who are given training opportunities will gladly share their experiences and ideas with colleagues at a meeting or brown bag lunch. So one small step toward lifting spirits is for upper management to commit to a healthy increase in newsroom training budgets.

Owners Who Care

Newsrooms also would be rejuvenated if staffers believed the owners had a genuine appreciation for their work and values. Adolph Ochs said his New York Times would cover the news “without fear or favor.” But some nouveau newspaper owners have demonstrated an appalling lack of judgment and knowledge about journalistic mission and ethics. In one particularly egregious case, a CEO proposed cash incentives to everyone, including reporters and editors, for selling advertising. A seminar on journalism credibility and conflicts of interest would be a valuable learning experience for executives tone-deaf to those fundamental values.

For my money, the Poynter Institute is the gold standard for industry training on everything from basic newsgathering to management leadership. Poynter and other professional groups—notably ASNE and the Newspaper Association of America—could do the industry a major service by seeking effective ways to address the heightened anxieties and hopelessness that persist in many newsrooms.

Poynter’s Jill Geisler is one of the few passionate advocates for doing more to attack plunging newsroom morale. In a commentary reflecting on managers’ handling (and mishandling) of repeated announcements of staff layoffs, she discussed the “new reality” of managers dealing with staffers who have no loyalty to their employers and “harbor deep resentments” toward their corporate bosses for failing to grasp the depth of grief associated with debilitating cuts in recent years.

Yet even in this somber scenario there is hope. Geisler argues that newsroom managers must rededicate themselves to helping staffers improve and do their best work. That’s why a training renaissance is vital for the salvation of high-quality journalism. Managers must learn to help their workers motivate themselves because self-motivated employees are key to any organization’s success.

When Warren Buffett announced late last year that he was buying the Omaha World-Herald, his hometown newspaper in Nebraska, a staff meeting erupted in cheers. Some were surprised by the reaction, but anyone who has read “The Snowball,” Alice Schroeder’s biography of Buffett, knows that he was a driving force behind the Omaha Sun winning a Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for exposing questionable financial practices at Boys Town, a venerable local institution for wayward youths. Buffett owned the paper and he helped editors and reporters decipher Boys Town tax returns.

What was the message in those cheers? Hope and pride in having an owner who believes in the power of journalism to change society and shine a spotlight on wrongdoing “without fear or favor.” Despair won’t get a foothold in a newsroom where the boss understands and encourages extraordinary work and gives the staff the resources to pursue it.

Skip Perez was executive editor of The Ledger in Lakeland, Florida for 30 years before retiring in 2011. He also served as senior editor for The New York Times Regional Media Group and vice chairman of the U.S. Freedom of Press Committee of the Inter-American Press Association.