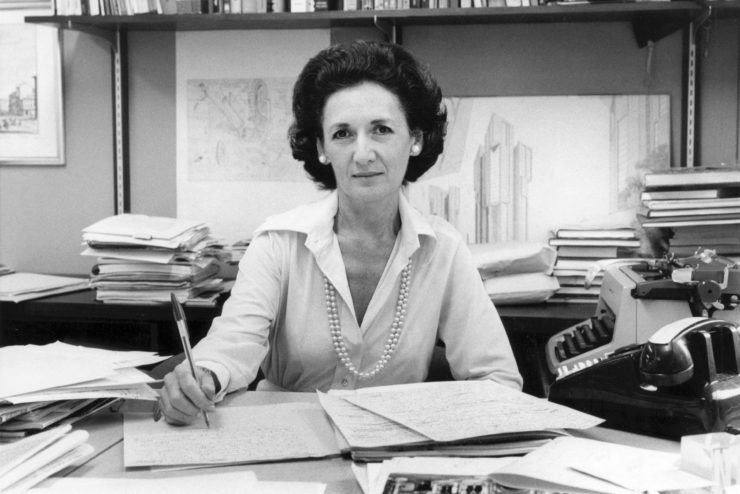

Ada Louise Huxtable, former New York Times architecture critic

In a recent Yale University lecture, Pulitzer Prize-winning Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin (NF ’13) explored a fraught issue many arts critics and their editors face in today’s polarized cultural environment: Where to draw the line between coverage of aesthetics and politics, art and power?

Kamin’s answer explores key influences on his writing, including “The Power Broker,” by Robert Caro (NF ’66), and discusses his own award-winning series of articles on Chicago’s lakefront.

Here are edited excerpts from the lecture, which marked the 50th anniversary of the Yale School of Architecture’s Master of Environmental Design Program (Kamin received a two-year research degree from the school in 1984):

Introduction

The images above and below speak to the tension between power and art—and the need for architecture critics to investigate that tension as they play the role of skyline watchdog. The woman above, the late Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times, almost single-handedly established the field of modern architecture criticism. Do not be fooled by her elegant earrings and strands of pearls. Mrs. Huxtable’s manual typewriter is a powerful instrument, a Stradivarius of journalism. Out of it come soaring insights and devastating takedowns. She is the personification of discernment and refinement—the very opposite of the man you see below.

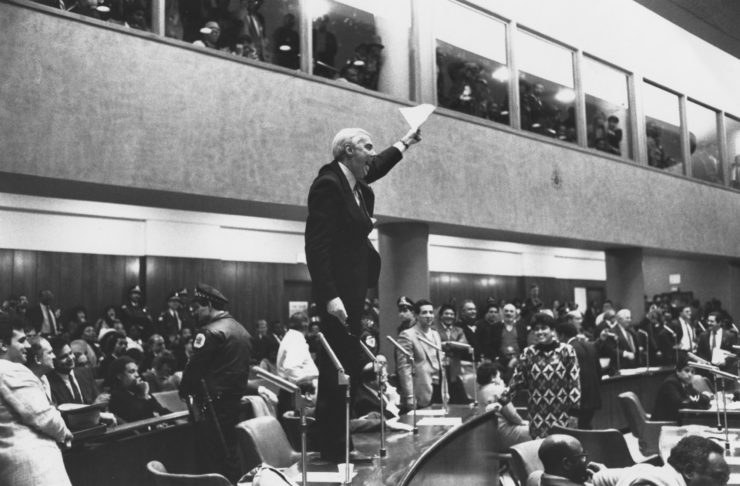

His name is Richard Mell and his behavior is as raw as Mrs. Huxtable’s is refined. As you can see, he is standing on his desk, screaming for attention. Mell is one of the 50 aldermen on the Chicago City Council. It is 1987. Mell and a bloc of white alderman are selecting a successor to Harold Washington, Chicago’s first black mayor, who has just died. The name of their game is power, just as the name of Mrs. Huxtable’s game is art.

Former Chicago alderman Richard Mell stands atop his desk in the City Council chambers

These disparate spheres would appear to be parallel universes destined to never intersect. But that is an illusion. Besides selecting the new mayor, the aldermen will pass judgment on every significant building proposal in Chicago. That should be a frightening thought because their pockets frequently are lined with campaign contributions from the very developers they are supposed to regulate.

Decades after these images were recorded, the tensions they symbolize still resonate. Should Mrs. Huxtable’s architecture-critic successors enter the raucous world of the aldermen in order to question—and, if need be—contest their judgments? Or should critics strive for a position of Olympian detachment, soaring above the fray so they can more easily observe its actions and discern its meaning?

In short, should architecture criticism engage in political acts?

My answer is plain: The formation of design literacy that empowers people to critically assess the plans that will affect them is a political act. Scrutinizing significant designs and the public officials who are supposed to review them is a political act. The promulgation of creative alternatives to tired plans that no longer respond to human needs or fail to anticipate future ones is a political act. In other words, critics should engage the political fray even if they aren’t in the political fray.

This is what journalists do. And it’s what they should do in a world where social media makes everyone a critic.

Influences

I learned something essential from Yale’s Master of Environmental Design program: A clearly-defined methodology can yield powerful evidence for making a critic’s case.

For me, two methods proved especially influential: One, pioneered by the author and journalist William H. Whyte, operated at the micro scale of a small urban space. The other, mastered by an even more distinguished author and journalist, Robert Caro, focused on the macro scale of an entire metropolitan region and the wielding of power that shaped—and mis-shaped—it.

For me, two methods proved especially influential: One, pioneered by the author and journalist William H. Whyte, operated at the micro scale of a small urban space. The other, mastered by an even more distinguished author and journalist, Robert Caro, focused on the macro scale of an entire metropolitan region and the wielding of power that shaped—and mis-shaped—it.

Published in 1980, Whyte’s “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” provided an invaluable guide to why city plazas worked—or why they didn’t.

He took time-lapse photos of plazas and carefully observed the characteristics that encouraged people to use them. He mapped sit-able space and patterns of pedestrian circulation. To a journalist like me who felt numbed by abstract architectural theory, Whyte’s focus on concrete reality and its impact on people was a breath of fresh air—and a major model.

If Whyte’s lens was intimate, Caro’s was sweeping. His Pulitzer Prize-winning 1974 book, “The Power Broker,” revealed how Robert Moses had for nearly half a century shaped the New York region’s roads, bridges, parks, playgrounds, housing projects, cultural centers, and stadiums even though he was never elected to public office. Moses did it, as Caro showed, by turning the public authorities he controlled into “a virtual fourth branch of government,” one that mobilized banks, contractors, labor unions, insurance firms and even the press “into an irresistible economic and political force.”

If Whyte’s lens was intimate, Caro’s was sweeping. His Pulitzer Prize-winning 1974 book, “The Power Broker,” revealed how Robert Moses had for nearly half a century shaped the New York region’s roads, bridges, parks, playgrounds, housing projects, cultural centers, and stadiums even though he was never elected to public office. Moses did it, as Caro showed, by turning the public authorities he controlled into “a virtual fourth branch of government,” one that mobilized banks, contractors, labor unions, insurance firms and even the press “into an irresistible economic and political force.”

Today, one can debate whether Caro was right to subtitle his book, “Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.” New York is rising, not falling, after all, and the city long ago left behind the existential threat posed by the 1970s financial crisis. Yet Caro’s emphasis on the need to reveal and scrutinize the hidden shapers of the urban landscape still rings true—just as it did during his Nieman year when he had an epiphany about the arid concepts professors were teaching in Harvard’s urban planning classes.

“Here were these mathematical formulas about traffic density and population density and so on,” Caro has recalled, “and all of a sudden I said to myself: ‘This is completely wrong. This isn’t why highways get built. Highways get built because Robert Moses wanted them built there. If you don’t find out and explain to people where Robert Moses gets his power, then everything else you do is going to be dishonest.’”

Such an approach would provide a valuable foundation for practicing architectural criticism in the bare-knuckled political environment of Chicago. It reinforced the need to focus not just on the world that architecture makes, but on who makes architecture.

Civic Criticism

The word “critic” derives from the Greek word “kritikos,” which means “skilled in judgment.” Critics judge. Their job is to separate the meritorious from the mediocre, and to articulate the standards by which such judgments are made. On that, I think there is little disagreement. Yet different forms of architectural criticism view the field through significantly different lenses.

There is, for example, criticism by omission: This approach, practiced by magazines like Architectural Record, publishes what the editors deem to be exemplary work—and leaves out everything else. These publications offers elegant photography and sophisticated texts. But they are addressed almost exclusively to a professional audience, not the broader public.

Then there is criticism by polemic: The critic articulates the principles of, and advocates for, a particular style, as Andrew Jackson Downing did in “Cottage Residences” or Charles Jencks did in “The Language of Post-Modern Architecture.” Architects are particularly fond of this approach because it’s the equivalent of a compass, offering a specific formal direction. But it, too, operates within a closed-circuit that excludes the public and is incapable of responding to the immediate issues of the day.

Ada Louise Huxtable took aim at this approach in the introduction to her 2008 book, “On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change.” She recalled: “I was once asked by a distinguished French journalist, ‘Just what polemical position do you write from, Madame?’ And when I failed to produce an appropriate polemic and replied that I wrote from crisis to crisis it was clear that I had failed to measure up to his expectations. I could have said that I wrote from a sense of entitlement, in the belief that everyone deserves, and has a right to, standards of quality, humanity, and yes, even art, because art elevates the experience and pleasure of the places where we live and work.”

Because I agree completely with her stance, I employ a different kind of criticism than criticism by omission or criticism by polemic: Civic criticism. It seeks to bring architecture, a subject that is simultaneously ever-present and esoteric, into the civic conversation.

Chicago’s Daley Plaza: A symbol of the need for a civic conversation in architecture criticism

The idea, as Mrs. Huxtable once said, is build a bridge between the public and the public realm. And that bridge, it should be stressed, runs two in two directions. Acting on the public’s behalf, the critic subjects the dreams and schemes of architects and developers to sharp scrutiny. Yet the critic also seeks to educate the public, to raise standards as well as awareness.

In civic criticism, the critic opens up the closed world of developers, city officials and designers and becomes an essential interlocutor in a democratic urban conversation about city design. The timing is critical. An essential part of this approach subjects decision-makers to scrutiny before decisions are set in stone.

Called activist criticism, this subset of civic criticism is based on the idea that architecture affects everyone and therefore should be understandable to everyone. It invites readers to be more than consumers who passively accept the buildings that are handed to them. It bids them, instead, to become citizens who take a leading role in shaping their surroundings. Its fundamental purposes are these: to stop hideous buildings and urban spaces from disfiguring the landscape, and to introduce constructive alternatives into the public debate.

Yet even some of the most sophisticated editors do not appear to value architectural criticism. This lecture is named for Brendan Gill, a distinguished Yale graduate and author who once served as the architecture critic for The New Yorker. Yet The New Yorker, whose pages have also been home to such eminent architecture critics as Lewis Mumford and Paul Goldberger, no longer has a staff architecture critic and rarely covers architecture. In addition, many financially-struggling newspapers have dismissed their architecture critics or have converted their beats to combined coverage of art and architecture. By my estimate, fewer than 10 American newspapers have full-time architecture critics on their staffs. That’s a serious problem. Because without skyline watchdogs, you get architectural mayhem—or deep-seated inequity in the way that governments parcel out resources for public space.

The Lakefront Series

Such imbalances were at the heart of a series of articles I wrote in 1998 about the problems and promise of Chicago’s greatest public space, its lakefront. The core of the series drew from the lessons I’d learned from Whyte and Caro, contrasting conditions on the city’s north and south lakefronts. Those conditions simultaneously reflected and reinforced Chicago’s long-standing racial divide.

The north lakefront was, and still is, something out of an old-fashioned postcard: A collection of public spaces lined by luxury high-rise towers whose occupants are largely white and wealthy. This section of the lakefront has easy access to the shoreline, via bridges and paths that cross over or under Lake Shore Drive, as well as an abundant supply of amenities—a zoo, lagoons, and broad swaths of parkland.

In contrast, the south lakefront, which was lined by public housing high-rises populated by people who were mostly poor and black, looked nothing like the sparking designs for it envisioned by Chicago’s great urban planner Daniel Burnham.

Its sea wall appeared as though it had been bombed. The bridges leading to it weren’t just long; they appeared intimidatingly long because of their ramrod straight geometry. This part of the lakefront had less of everything—less land, fewer food concessions, fewer restrooms, you name it. Beaches identified on a map had disappeared under the waves.

A new marina on Chicago’s rebuilt south lakefront

The shoreline’s separate and unequal status was no accident. It was the outcome of systematic racism—specifically, a decades-long policy of “benign neglect” In essence, the Chicago Park District steered resources toward white neighborhoods and away from those populated by blacks and Latinos.

The series, “Reinventing the Lakefront,” shed light on this deplorable situation and provoked a public debate.

Following its publication, former mayor Richard M. Daley and the Chicago Park District authorized or altered plans for four of Chicago’s seven lakefront parks, an area of nearly 2,000 acres and more than 10 miles of shoreline.

Nearly 20 years later, those plans have led to some dramatic changes. The once-barren south lakefront now has a rebuilt shoreline, a marina with a playground and a graceful suspension bridge that provides easy access to the shoreline from the neighborhoods to the west. And more improvements are in the works. To be sure, such changes have not prevented the ongoing gun violence that has wracked Chicago’s South and West sides, but they do provide a respite from that violence as well as an emerging design equity in the quality of public space.

Conclusion

As such exmples show, the heart of civic criticism is the ongoing conversation it begins—the one that brings the public into the dialogue about the public realm. This approach can work on the national level as well as the local level, as illustrated by a column I wrote last April about designs for President Trump’s proposed border wall.

The column asserted that we should not fall into the trap of choosing alternatives for this fundamentally misguided idea, which would divert funds from the critical task of rebuilding the nation’s crumbling infrastructure, be ill-suited to varying terrains and become, for many, a permanent symbol of American xenophobia—the anti-Statue of Liberty.

Notice that I didn’t say the border wall is a stupid idea. My editors wouldn’t let me do that.

They wanted me to stay in my lane—the critic’s lane, a lane they see as emphasizing policy, not politics. In other words, they wanted me to be of the fray, not in the fray; combative but clear-eyed; passionate but not partisan. I accept and embrace that position even though I know how hard it is to achieve, at least in the eyes of border wall supporters who consider any criticism of the wall to be tainted by politics.

The battle never ends, as I was reminded when President Trump unveiled his so-called tax reform plan and historic preservationists alerted me to a little-noticed House provision that would end the long-standing historic tax credit provision that has spurred billions of dollars in investment and has helped to save countless buildings in big cities and small towns.

Getting this news out there, at the top of the front page, offered a timely reminder of the essential intersection between architectural criticism and political acts and the critic’s prime responsibilities: 1) Conduct a civic conversation about architecture; 2) Separate the meritorious from the mediocre; 3) Enter the political fray when necessary, and 4) Always, always, always hold the powerful to account.