Illustration by Harry Campbell

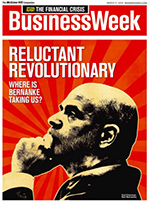

In 2008, the year of the financial crisis, BusinessWeek magazine pictured Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke as a driver careening down a mountain road, then as Vladimir Lenin, then as a Dutchman trying to plug a leaky dike, then as Edward Scissorhands cutting interest rates, then as a human printing press with sheets of newly minted bills coming out of his mouth. Each week of the fast-moving crisis seemed to call for a new metaphor.

In the years since, my stories in Bloomberg Businessweek (our name since December 2009) have portrayed Bernanke as a rainbow-bearded Bob Dylan, a lighthouse keeper, a Swede, a person with two birds inside of him, a bather in a bubble bath, and a sooty engineer trying to restart a disabled cruise ship.

Turning the world’s most powerful central banker into “Hugo: Man of a Thousand Faces” wasn’t about a bunch of magazine writers and illustrators trying to crack each other up. Well, not just. I argue that the metaphors we chose elucidated the financial crisis in a way that charts, quotes, factoids and statistics couldn’t. They weren’t just for decoration. They were part of the scaffolding on which my articles were built.

If you aren’t making up your own metaphors, you’re probably using someone else’s. Trying to communicate without using any metaphors would be like trying to complete a paint-by-numbers canvas without red, blue, yellow and green. Even professional economists use metaphors. Ben Bernanke coined “fiscal cliff” last year. “Liquidity” is such a common term in technical economics that we forget that money-as-fluid is really another metaphor. John Maynard Keynes used metaphors constantly. He said that trying to increase output by increasing the money supply “is like trying to get fat by buying a larger belt.” He blamed the Great Depression on “magneto trouble”—a faulty alternator under the hood that prevented the car from running.

Professional economists claim to be doing something entirely different from journalism, but the axioms and lemmas in their papers are only as good as the assumptions on which they’re based. Mary S. Morgan of the London School of Economics writes in “The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think” (2012) that for economists metaphors lead to analogies, and analogies lead to models, which are the tools, often in the form of equations, that economists use to understand the world. That process only works, though, if the starting point is valid. Garbage in, garbage out. Keynes dismissed lots of mathematical economics papers as “mere concoctions, as imprecise as the initial assumptions they rest on.” The economist Kenneth Boulding said, “Mathematics brought rigor to economics. Unfortunately, it also brought mortis.”

Metaphors work because they hit people subconsciously, bypassing our rational minds and tapping into unconscious ideas and associations. An academic analysis of CNBC’s “Business Center” found that, on days when the stock market went up, anchors usually portrayed the market as the master of its own fate: Stocks “jumped” or “soared.” On down days, they often switched to passive metaphors: Stocks “got caught in the downdraft.” The picture they drew of a market heroically fighting its way upward against stiff resistance probably influenced viewers more than if CNBC had come right out and said “Stocks will keep going up,” which would have set off alarm bells.

In fact, the academic analysis found that people exposed to active metaphors such as “jumped” were more likely to think a market trend would continue than those who were given passive metaphors. In another experiment further removed from economics, readers of a text that likened criminals to wild animals (“packs” of youths “preying” on people) came up with crime solutions consistent with actual wild animals (“lock ’em up”), while those who heard virus metaphors (crime “infecting” our neighborhoods) came up with solutions consistent with viruses (“clean up our communities”). A metaphor, like a handgun, can be used for good or ill. A good one gets at some truth and provokes a shock of recognition by linking two things that don’t usually go together—say, high finance and heavy drinking.

I make no excuses for describing the economy and the stock market as “two staggering drunks connected by a long rope.” Nor for likening European debt negotiations to the sanatorium therapy in Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain,” “dragging on interminably as the patient sinks into a permanent malaise.” Nor for diagramming China’s currency strategy as if it were a football play (the “Beijing Crawling Peg”). Nor for borrowing Representative Emanuel Cleaver’s description of the 2011 debt-ceiling deal: a “sugar-coated Satan sandwich.” And I definitely don’t apologize for comparing JPMorgan Chase’s vaguely defined portfolio hedges to “a billowy muumuu” that hides a multitude of trading sins.

I recently interviewed Paul Krugman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, about how he manages to find new ways to make the same points over and over in his New York Times column: Austerity is bad; there’s no threat of inflation; now is not the time for budget cuts, etc. (“How to Beat a Dead Horse” was our headline.) Metaphors, Krugman said, are invaluable: “Sometimes, you can be mulling over an issue for years before the right thing comes to you. ‘Confidence fairy’ has been a good friend to me. That one just came out of the blue in 2010.”

Ununquadium came to me in 2010. I was trying to convey the idea that the single-currency euro zone was at risk of bursting apart. Poking around on the Internet I found out that right at the time the euro was launched in 1999, Russian scientists synthesized a super-heavy element with 114 protons called ununquadium. “Alas,” I wrote, “ununquadium (‘oon-oon-QUOD-ee-um’) is too unstable to exist in nature. The force binding its nucleus together is overwhelmed by the force tearing it apart.” Just like the euro!

Stephen Shepard, who was editor-in-chief of the old BusinessWeek for years, used to say, “You can’t beat something with nothing.” I think that truism applies here. Readers come to our stories with something in their heads—a mental construct, a way of seeing the world. If I don’t manage to dislodge that mental construct by offering what I think is a better one, then all the statistics and charts and authorities that I throw at the reader will slide off like hot butter on Teflon.

The stakes are higher than just whether readers get an article. Families that make financial decisions based on the wrong metaphors could lose their savings. Policymakers could drive their economies into a ditch. I think that’s what’s been happening in Europe, where German Chancellor Angela Merkel likens herself to a thrifty Swabian housewife. Her self-portrayal is disarmingly modest, but paralyzing.

For a cover story this January I challenged the metaphor that a nation’s economy is like a family in need of frugality. “While a single family can get its finances back on track by spending less than it earns, it’s impossible for everyone to do that simultaneously,” I wrote. “When the plumber skips a haircut, the barber can’t afford to have his drains cleaned.” Keynes said as much 80 years ago. I argued that the economy is less a profligate family than an engine stuck in low gear. “It doesn’t need a disciplinarian; it needs a mechanic.”

Journalists need to be mechanics, too, tinkering with our metaphors until we get them right. Control your metaphors, or they will surely control you.

Peter Coy is economics editor of Bloomberg Businessweek magazine. He previously was technology and telecommunications editor.

Peter Coy is economics editor of Bloomberg Businessweek magazine. He previously was technology and telecommunications editor.